Kylie Wright spent a lot of time with late indie rock icon David Berman while they were students at the University of Virginia. They both hosted radio shows in WTJU’s not-so-coveted 2 to 6am slot. His: “The Big Hair Show.” Hers: “Jane Fonda’s Blackout.”

But when asked about her time with the poet and singer-songwriter, the first story that comes to Wright’s mind is set in the university’s library. The two aspiring musicians were studying one day when Berman decided to use the library’s suggestion board. “How would you improve the library?” the board queried. “More bass,” Berman answered.

Several days later, library staff responded: “We’re more ‘trout’ people.”

“David saw that and said, ‘My work here is done,’” Wright says. “He could really be a very funny person.”

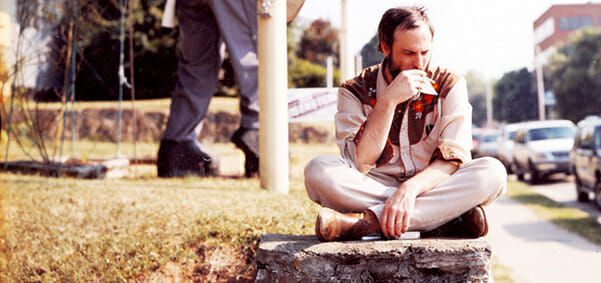

Since Berman’s suicide in 2019, the media has focused much on the former Silver Jews frontman’s demons. He was a reclusive loner, they report, tormented by self doubt and addiction.

Back at UVA, though, Wright remembers how communal the budding lyricist’s energy was. WTJU was a fraternity/sorority for their friends, she says, and the group’s creativity worked in pure synergy.

It’s that sort of synergy that WTJU will try to perpetuate with its recently announced David Berman Memorial Fund, the station’s first dedicated endowment. According to WTJU General Manager Nathan Moore, the fund will be earmarked to support student experiences at both WTJU and WXTJ—much like those transformative programs Berman and his friends enjoyed in the late ’80s.

“Our mission is to bring people together through excellent music conversation,” Moore says. “We’ve been doing that for decades and decades.”

During his time at UVA and WTJU, Berman crafted the logophilic artistic approach that made him and the Silver Jews—founded alongside Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich of Pavement fame—influential for years to come. Berman was always as much a poet as a songwriter, painstakingly crafting lyrics for the Silver Jews, and later Purple Mountains, that reflected humanity’s greatest weaknesses and insecurities. His one collected work of verse, Actual Air, drew perhaps even more acclaim than did his song lyrics, with many critics praising the poetry’s blunt wit and absurdist take on American life.

When UVA alumnus Andy Stepanian approached Moore about starting an endowment, they agreed a fund in Berman’s name would be a perfect fit. “As a student, I tuned in to WTJU because it was always a place to hear alternative music,” Stepanian says. “I still have cassette tapes of some WTJU programs I recorded back in the early ’90s.”

Stepanian and his wife Liz provided the seed gift to start the memorial fund, but Moore says the station wants the legacy to go further. Additional donations, which the Stepanians will match through the end of summer 2024, will be required to maintain the program.

In the past, WTJU’s summer student internships have mostly been unpaid, something Moore says is inequitable—reserved for those who can afford to forgo income for three months. Indeed, many publicly funded radio stations, including NPR, have done away with their internship programs, citing their high cost.

With further donations, Moore says WTJU can continue to provide the kind of experience that let Berman, Wright, and their friends nurture their creativity, engage in the arts, tell stories, and learn the technical side of the music and radio business.

“It’s a privilege that can launch people into fantastic lives and careers,” Moore says. “This will help us grow the program and sustain it and perhaps expand it.”

Before he died, Berman was planning a Purple Mountains tour. Wright had tickets to see the band in Philadelphia. She emailed Berman to let him know she’d be there, and he responded with a promise not to do what he always did after shows: disappear. The next day, she heard the news of his death.

“I remember writing at the time that we lost the best and brightest in our group,” Wright says. “I think he had been fighting for years, and the strain of the upcoming tour was too much.”

Moore says he didn’t know Berman when he was alive, but he’s a fan of his music, lyrics, and voice. And he’s gotten to know more about him by meeting friends like Wright. The portrait is one that so many have come to know—the outsider, the disrupter, the sometime anarchist. But it’s also a portrait of an artist who embraced both people and creativity in all their forms.

“I used to listen to his show. I would come hang out sometimes, and we all kind of fed off of each others’ musical interests,” Wright says. “The media would try to build him up as this sort of brooding poet, and in actuality, it was about having his tribe around him. I just feel lucky that I was in the right time and place in history to have met David. I miss him all the time, but I’m glad his memory is being kept alive and that this is going to help young people in music.”