Sue Holden is a lousy musician. So instead of standing in the spotlight, she’s backstage and frontstage and in the wings and behind the curtains running security and supervising the ushers at the Charlottesville Pavilion, the JPJ and the Paramount, ensuring that you can see a really good musician. And I mean “see,” literally—when I find Holden at the first fully seated show of the 2007 Pavilion season (Bonnie Raitt), she is talking down a disgruntled patron in section 203 who claims she can’t see the stage because an usher is standing in her sightline in section 103. I can feel my blood boiling at the snippy tone of the cranky customer who seems to think her seat in 203 is more important than those of the folks the usher is helping in 103 (who, uh, paid more) and who seems to think she’s going to miss Bonnie in some choreographed visual spectacle involving chair dances and whipping boys à la Madonna. Holden, however, keeps cool as she calls up the usher on her walkie-talkie and tells him to sit the hell down (emphasis added). And without a second thought, Holden is off to diffuse the next seating situation (a mismarked row of seats that leaves two ticket holders chairless) before she makes her next periodic water and candy distribution run to the security and ushering staff posted throughout the house. “I’ve worn a pedometer a couple of times, and we put on between five and six miles per show—we move constantly,” says Holden.

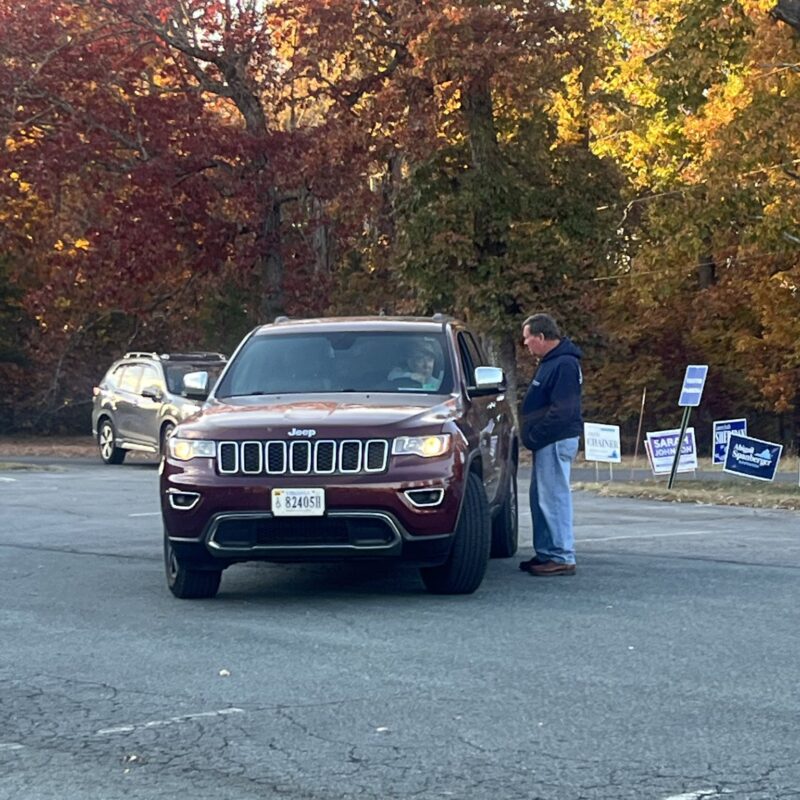

Sue Holden and Ron Morgenegg prepare for a Saturday spent running security and ushering seas of screaming kids at the JPJ’s “Sesame Street Live” performance—and it ain’t even their day jobs. |

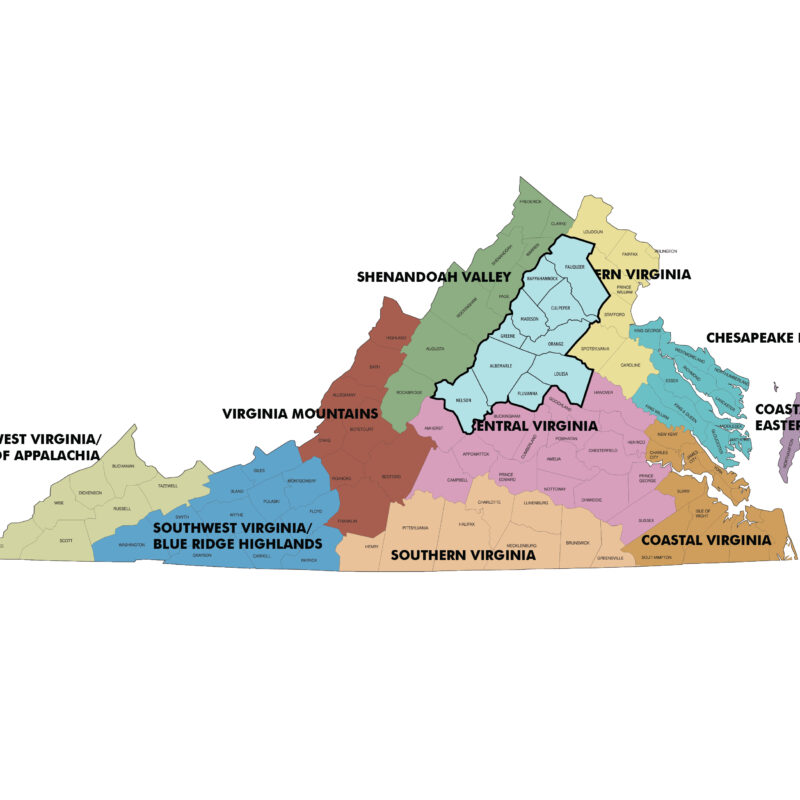

Holden and her co-staff supervisor, Ron Morgenegg, are running the show at the three biggest music venues in town. And it ain’t even their day jobs. When Holden isn’t finding a new, “more comfortable” seat for the rowdy young couple who wants to stand up and dance to Willie Nelson’s “Whiskey River” in front of the elderly couple who just wants to sit and sway, she’s co-chairing the special education program at Albemarle High School, and when Morgenegg isn’t telling the hellions to put out that, ahem, cigarette at the JPJ, he’s working in the forensics unit of the Charlottesville Police Department.

Herding high schoolers and solving crimes seems to be good training for their music gig. But Holden, who started out as a volunteer usher at the Paramount, finds her rise in event security somewhat amusing. As for her accidental second career, she says, “A little extra money never hurt, and I like being busy, but it’s grown. Now we’re running it. It’s kind of gotten a little ahead of itself.”

So why do Holden and Morgenegg spend their free time—25 to 30 hours a week, four to five nights a week—dealing with the often ungracious public? It’s their love of music, for sure (Holden plays some instruments, badly she says, and Morgenegg used to play the bagpipes). But when I ask if they are able to enjoy the performances while they work, the answer is an emphatic “No.”

“But it’s O.K.,” Holden says, “I got to shake hands with James Brown” at the Pavilion. And at the Paramount, she shared a chili dog with Bill Cosby, and spent an amusing evening covertly flashing the Mets score to Itzhak Perlman per his request.

So perhaps it’s a love of the backstage “scene,” of getting to wear those insidery Staff t-shirts, that keeps Holden and Morgenegg coming back for more evenings of bouncing drunks and chiding parents to keep their kids from flipping around the Pavilion’s railings. Both Morgenegg and Holden call the group of 30 or so locals whom they supervise as ushers and security staff a “community.” The crew, which makes about $8 an hour, runs the gamut from blue collar types to a few with master’s degrees and doctorates, says Holden. But all of them, I suspect, are junkies for the adrenalin rush that comes from telling ticket holders to douse the doobie just as much as from rubbing elbows backstage with the likes of Lyle Lovett and Loretta Lynn. Not a bad gig.