The University of Virginia has many storied traditions. One, that of the Virginia gentleman, contributed to UVA being the last public university—aside from military institutions—to allow women. Spurred by a lawsuit, the school admitted its first class of female students in 1970.

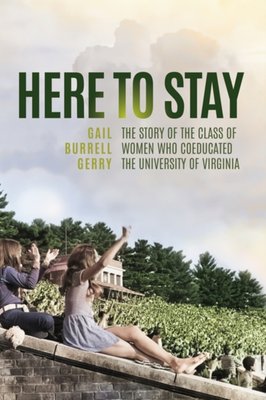

Gail Burrell Gerry was a member of that class of 367 women, and she had no idea what she was getting into. She documents the experiences of the class of ’74 in her book Here to Stay: The Story of the Women Who Coeducated the University of Virginia, published by the University of Virginia Press in March.

Gerry, a “proud Michigander,” didn’t realize UVA only admitted men when she applied in late 1969, nor did her high school counselor in Ypsilanti. Her first clue was receiving an acceptance letter from Mary Washington College, then the women’s college for UVA, to which she had not applied. “My first acceptance letter didn’t make any sense,” she recalls.

Shortly after, she received one from UVA.

An educator and researcher, Gerry is well-equipped to tell the story of the first coed class, about which even getting the exact number took a deep dive into the archives. “I wanted to find the primary documents,” she says. “My goal was to show the human side of institutional transformation.”

Edgar Shannon was president of the university during the tumultuous ’60s, when the Vietnam War, civil rights, and equal rights were roiling college campuses. “He truly believed you couldn’t have a great university without the diversity of races, ethnicities, religions, and genders,” Eleanor Shannon, one of the president’s five daughters, told Gerry.

UVA didn’t admit Black students until 1950, the result of another lawsuit, this one brought by Gregory Swanson, and even then, it was only a handful of men.

As early as 1964, Gerry discovered, university officials knew that its men-only policy was discriminatory. Women in Virginia were well aware they could not study at the commonwealth’s flagship university, and in 1969, Charlottesville resident Virginia Scott and three other women sued in federal court for admission to the College of Arts and Sciences.

So why did it take so long? “I really think it was discrimination,” replies Gerry.

“Many men were resistant,” she says, and some wore buttons that said BBTOU—Bring Back the Old University.

She recalls a public-speaking class in which a male classmate, wearing a tie, khaki pants, and a BBTOU button, explained that women had ruined the university and its long tradition of the Virginia gentleman. “Our faces were burning,” she says. “We were told over and over that most men didn’t want women there.”

She stewed about his presentation, and a couple of weeks later, showed up in class wearing hot pants and gave a “provocative” speech detailing how she was only there to find a husband—a common stereotype from those who wanted to keep UVA a male bastion. Her classmates laughed.

“At 19, I could laugh about it,” she says. “I’m not now.”

She found that among the 367 female first years and 301 women who transferred from Mary Washington, who were already allowed to study nursing and education at UVA, there were 100 pregnancies. She points out that birth control pills were not legal in 1970, and there was no student health for women. “To see a gynecologist, you had to go off campus.” She notes, “We didn’t have transportation,” and the bus system didn’t exist at that point.

Safety was a big issue for the women, and “almost everyone had stories about feeling unsafe,” says Gerry. “We had to walk everywhere.”

Even before women arrived, Annette Gibbs, associate dean of student affairs, pointed out to university officials how dark the Grounds were. The response was that the aesthetics of Mr. Jefferson’s college had to be protected. “That was very discouraging,” says Gerry.

She initially wasn’t going to broach the topic of rape. But it came up during interviews and reunions, and if it wasn’t a first-hand experience, everyone seemed to know a roommate or classmate who’d had an unwanted sexual encounter. Gerry had vowed to report what she found.

“We didn’t have the language about date rape in 1970,” she says. “The image of a rapist was a scary stranger. It wasn’t someone you knew.”

The idea of writing about her pioneer class first occurred to her in the run up to the 2016 presidential election, in which Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton. ‘I became aware of the sexist language being used,” says Gerry, “and it was very concerning to me.”

By the time she finished writing, the U.S. Supreme Court had overturned Roe v. Wade, and “women lost the right to choose and have control over their own bodies,” she says, an unwelcome flashback to 1970.

Many of her classmates cite the strong friendships they developed while at the university, and said that was the best part of their higher education. Gerry points out that her class was the first generation of women to work full time while raising families. “My years at UVA were foundational to my later life.”

And while she did not attend UVA to find a husband, Gerry, in fact, did meet her husband there, and they’ve been married more than 50 years. “Part of my UVA story,” she says, “is a love story.”

Gail Burrell Gerry (top left, above) details the experiences of female students in the class of ’74 in her book Here to Stay: The Story of the Women Who Coeducated the University of Virginia. Supplied photo.