Here’s a riddle. When is rainfall bad for the environment? Answer: when it becomes “stormwater runoff,” washing sediment and excess nutrients off yards and fields, then into streams, rivers and eventually the Chesapeake Bay.

|

Under new regulations to reduce stormwater runoff, the site at 301 W. Main St. would be required to reduce phosphorus runoff by 20 percent. Morgan Butler of the Southern Environmental Law Center says that such reductions can be achieved by installing green roofs and harvesting rainwater, among other things. |

Such pollution is a complex problem that has many sources and degrades many points downstream, so it’s fair to say the state Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) has a tough job trying to stop it. One measure DCR is taking right now is a set of proposed changes to the way it regulates stormwater management on developed lands.

Now here’s another riddle. When are pollution controls bad for the environment? According to some local watchers, they could be harmful if—in seeking to protect the bay—they end up promoting sprawl instead.

The most obvious target of the regulations: sizeable new projects on undeveloped land. David Slutzky, chairman of the Albemarle County Board of Supervisors, mentions North Pointe (a major development off Route 29N, within one of the county’s designed growth areas) as an example of the type of project that could suffer from what he sees as potential unintended consequences of DCR’s plan. If developers become subject to tighter controls on the amount of sediment and phosphorus that can legally wash off their land, he worries, they’ll be forced to downsize the density of their projects or, in extreme cases, scrap them altogether.

“‘I can’t afford to move forward. This is no longer an economically viable development project,’” Slutzky envisions developers saying. “[Then] a large tract of land just sits in the growth area.” In turn, he says, growth will be pushed into rural areas, contributing to sprawl.

Writing as a private citizen, Slutzky submitted comments to this effect during DCR’s public comment period, which ended August 21. Morgan Butler of the Southern Environmental Law Center expects that a compromise will be struck in which developers unable to meet DCR requirements through on-site measures (which might include rain gardens, rainwater harvesting, green roofs and other practices) could buy credits instead. Slutzky has argued for developers being given off-site options like paying into a DCR fund, or contributing money to changes in the agricultural sector, another major source of runoff pollution.

What about the city?

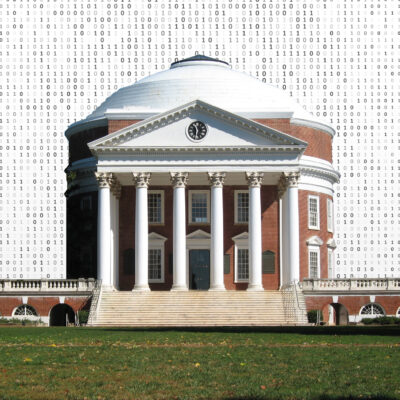

The proposed changes would also affect redevelopment sites in urban areas—for example, the 1.03-acre lot at the corner of W. Main Street and Ridge/McIntire, where a furniture store has recently opened and a nine-story condo-and-retail project was proposed as recently as June 2008. (Plans are still pending; the last developer to present plans to the city, EDC in Richmond, is no longer working with the site, and architects Morrison Seifert Murphy did not return calls by press time. CBRE lists the property, which also includes an unused brick garage, for $4.8 million.)

An almost entirely paved site, under the proposed regs 301 W. Main St. would be subject to requirements that phosphorus runoff be reduced by 20 percent, double the reduction currently required. Butler says there are a number of ways to do this on-site, including green roofs and rainwater harvesting. “Even beyond that, there are other safety valves that DCR is putting into the regulations,” he says.

If those safety valves end up reducing pollution on faraway farms rather than on-site at W. Main Street, it will help the bay but not its local tributaries. According to Butler, both the EPA and the state Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) have declared an 11-mile stretch of the Rivanna River to be impaired by sedimentation.

And of the three main sources of nutrient pollution in the Chesapeake—sewage treatment, agricultural runoff and stormwater runoff—it’s the last area, says Butler, where the problem is getting worse instead of better. “The state has made progress on reducing the first two, but the amount of nutrient pollution on developed lands continues to increase,” he says. “It’s outweighing progress made on the other two fronts. It’s critical that something be done on this piece of the problem.”

C-VILLE welcomes news tips from readers. Send them to news@c-ville.com.