Frank Morris had trouble breathing.

Victor Taylor woke up in the middle of the night, with “pancake-sized hives.”

Author John Grisham’s ears were “really, really itching.”

“We got in the car,” Grisham told Allergic Living magazine, “and I was so desperate I stripped down, took off all my clothes but my boxer shorts, and I had all the air blowing on me, and you could just see the welts.”

The cause of these mysterious reactions?

Red meat.

UVA physician Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills discovered alpha-gal allergy, commonly known as the “meat allergy,” in 2002. One of the more perplexing human allergies, it occurs when sufferers become sensitized to alpha-gal, a type of sugar present in red meat. Alpha-gal causes a delayed reaction—an affected person may eat meat, then break out in hives hours later, or even have trouble breathing. And because the allergy is believed to be triggered by a tick bite, you can develop it as an adult, even if you’ve been eating meat all your life. While it’s often associated with beef, other meats like pork, lamb, or goat can cause the reactions.

“People think it’s just red meat, but it’s all mammals,” Platts-Mills informed a patient at the UVA Allergy Clinic this fall, in his patrician British accent. “Anything with titties and hair.”

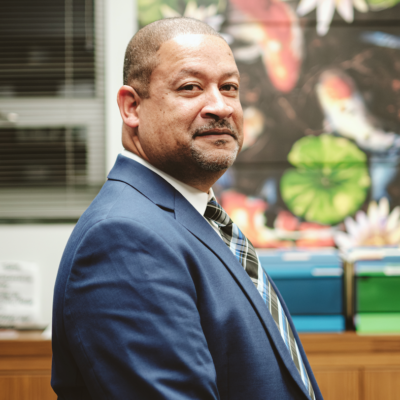

The patient, Greene county resident Frank Morris, had been diagnosed with alpha-gal allergy about a year ago, after a pork barbecue sandwich sent him to the emergency room with a rapidly swelling throat. “It was a really scary thing that night,” he says. “I usually don’t like to go to the doctor…but I couldn’t breathe, I was fighting for air.”

Platts-Mills and his team took him off beef and pork, and Morris says he was doing well. But he was back in the clinic that day after starting to have more allergic reactions, this time to dairy products. Recently, a few sips of a milkshake had made his lips swell up.

“You’re lucky,” Platts-Mills tells him. He says that with alpha-gal, most people don’t get the immediate mouth swelling that provides a heads-up that they are eating something potentially dangerous.

Sure enough, the allergy test confirmed Morris’ new sensitivity to milk, and pricks for beef and pork still produced tell-tale itchy red bumps. He was also tested for chicken, turkey, and fish, all of which came up negative. “You don’t even like fish,” his girlfriend Margie observed. But she was happy the couple at least knew the cause of his symptoms—before his trip to the ER, Morris had spent about six months getting various other diagnoses and medications from his primary care doctor.

That lack of awareness may be starting to change. “It seems like everyone either has it or knows someone who has it,” she says.

Dr. Thomas Platts-Mills, a UVA physician, discovered alpha-gal allergy, commonly known as the “meat allergy,” in 2002. One of the more baffling human allergies, it occurs when sufferers become sensitized to alpha-gal, a type of sugar present in red meat. Photo: Amy Jackson Smith

Discovering the allergy

Platts-Mills, the son of a barrister and a British member of Parliament, is the head of the Division of Asthma, Allergy & Immunology at UVA. His discovery began more than a decade ago, when he was asked to look into severe allergic reactions to a cancer drug, cetuximab. With a team of researchers, he found they were allergic to a particular ingredient in the drug—alpha-gal. Patients had developed antibodies to the sugar.

At the same time, reports of a similar allergy were arising in Platts-Mills’ clinic, independent of the cancer drug. Doing the cancer-drug allergy work, Platts-Mills helped to develop an allergy test (called an assay) for alpha-gal.

“I think the thing that I did, better than anything else, was to say we need to assay everybody in the clinic, anyone who would stand still,” Platts-Mills says. “We wanted to see what this related to.”

Researchers noticed that patients having alpha-gal reactions lived in the same area as a type of tick-borne disease, and wondered if the allergy might be triggered by ticks. (Platts-Mills says a technician on his team, Jake Hosen, was the first to suggest this connection.)

Pursuing that hunch paid off. The Platts-Mills team was able to find blood samples from people taken before and after tick bites, and to show the rise of antibodies to alpha-gal after they were bitten, ate meat, and had a reaction.

Then, Platts-Mills got the allergy himself.

In summer 2007, while this early research was happening, Platts-Mills recalls going for a hike, and having to remove tiny ticks, called seed ticks, from his legs afterwards. He ate meat rarely, but that November, he ate two lamb chops with two glasses of red wine.

“It was four to six hours later that I was covered in hives,” he says.

Ever the researcher, Platts-Mills tracked his alpha-gal antibody levels over time. He had his blood taken every week and watched the level fall as he avoided red meat and rise again after a different tick-bite incident followed by a meat meal. “I’ve done it a few times,” he says.

In March, 2008, Platts-Mills, along with Hosen and others, published a seminal article on the allergy for the New England Journal of Medicine. It has since been cited more than 1,000 times.

Alpha-gall allergy has a unusual delayed response. With a peanut allergy, Dr. Platts-Mills says, if you were exposed at a restaurant you’d know before you left. Whereas with the alpha-gal response, “you could eat a hamburger, sit for hours chatting with friends, wander out,” and still have no idea that you will have a big reaction later.

Dramatically different

Platts-Mills says alpha-gal is dramatically different from other food allergies. For one thing, unlike most allergies, alpha-gal is not species specific. “You can react to meat from a number of species,” he says, adding that some people even have reactions to eating squirrel or some other kinds of roadkill.

The delayed reaction is also not the usual allergic pattern. With a peanut allergy, Platts-Mills says, if you were exposed at a restaurant you’d know before you left. Whereas with the alpha-gal response, “you could eat a hamburger, sit for hours chatting with friends, wander out,” and still have no idea that you will have a big reaction later.

“We had a patient whose symptom was very low blood pressure, who had eaten meats all life long,” Platts-Mills says. “Just recently the symptoms started after eating meat. Three hours later, serious illness set in. You have the enigma of a person who perhaps has been eating meat for 30 or 40 years who flips into this new state.”

While the most common reaction is hives or intense itching, the allergy can also cause stomach pains, trouble breathing, and in some cases even anaphylaxis, a potentially life-threatening condition in which the body goes into shock.

Sensitivity to alpha-gal may also affect the circulatory system. An early-stage UVA study of 118 people found that those with sensitivity to alpha-gal, whether they showed allergic symptoms or not, had about 30 percent more plaque build-up in arteries than those who weren’t sensitive. The researchers also found that more of the plaques had features characteristic of unstable plaques, which are the type more likely to lead to heart attacks.

Study leader Coleen McNamara, a cardiologist who also works in UVA’s Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center, says that research calls for further clinical studies.

Putting the bite on

In our area, the alpha-gal effect seems to be primarily caused by the lone star tick, which is found on larger mammals like deer and dogs. The larvae of the lone star tick can also bite us. After feasting on our blood, mother ticks can lay 5,000 eggs, which appear as tiny specks that we call seed ticks, Platts-Mills says.

“Some people, slightly wrongly, call them chiggers,” he says. Tiny black dots you may see on your leg are most likely the larvae of the tick, he explains. They are nearly invisible.

When you get these bites, they strongly itch, which can last for a couple of weeks. If the itching reaction persists, Platts-Mills says, you may be more likely to be sensitized to meat.

“We think it is something definitely happening in response to the injected saliva of the tick, which is a complicated substance,” Platts-Mills says. “The injection into the skin causes the trouble.”

Victor Taylor, who lives in Afton, is a frequent hiker and got tick bites in the woods. He remembers one bite that didn’t heal for two weeks. “Once I removed the tick, it itched terribly,” he says. The area of the bite swelled to about the size of a quarter.

An infrequent beef eater, he had a steak a while after the initial tick bite. He awakened at 2 or 3am, and was very itchy, covered with very large hives. He had never had hives before.

“At first, I tried to take a bath to relieve the itching, but I had no idea what was causing it,” he says. The hives returned on another occasion, after he ate spaghetti with meat sauce, and then a third time after pizza with Canadian bacon on it. That’s when he realized it was a meat problem.

“I hadn’t heard anything about a tick-related allergy,” he says. “This was in 2010.” But he was treated by a nurse who had read a paper about how ticks were causing the allergy to meat and to certain cancer drugs.

In other parts of the world, Platts-Mills says, the same alpha-gal effect is happening with other ticks. He is helping a team in Minnesota to study alpha-gal outbreaks there. “It seems to be more the American dog tick in the Midwest, which is rare in Virginia,” he says.

As an aside, he adds that the tick that carries Lyme disease, often called the deer tick, actually is predominantly a mouse tick, a different species. “The bites that transmit Lyme disease generally do not itch. That species’ larvae can’t or don’t bite humans.” Researchers are “about 99 percent sure” that the tick that causes Lyme disease does not cause alpha-gal, he says.

Alpha-gal allergy and other tick-borne illnesses are a growing problem, because ticks are more prevalent in the spaces where we live. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that cases of tick-borne illnesses doubled between 2004 and 2016, though it does not yet recognize alpha-gal allergy among these).

This is partly due to climate change, which has vastly increased the population of lone star ticks, which thrive in warm, humid weather. The ticks have expanded their range (all the way up to Maine), and warmer winters mean they’ve been able to stay active longer.

Another factor is the overpopulation of white-tailed deer, which carry the ticks. Deer stroll through many a yard and park in Charlottesville and surrounding counties, especially as increased development has pushed houses further into deer habitat. “We’re living too closely to them,” says Platts-Mills. “This simply was not happening in 1950.”

It’s hard to believe, but Virginia’s deer population was almost non-existent in the early part of the 20th century. The Virginia Game Commission began re-introducing deer to the Blue Ridge in the late 1940s or early ’50s, after commercial hunting had nearly wiped out the population. From a statewide low of about 25,000 in 1930, the deer population grew nearly tenfold by 1970, to about 215,000, according to deer project coordinators with the Izaak Walton League, a conservation society.

Today the deer population in Virginia hovers at about a million. That’s worrying, says Platts-Mills, because it is not unusual for a single deer to have 500 mother ticks busy fattening up, and deer have no way to remove the ticks from their bodies.

Treatment, but no cure

To treat a reaction, Platts-Mills says Benadryl generally works if you’re someone who just gets hives.

While the doctor’s own reactions have been “uniformly non-frightening,” he says scientists still don’t know why some people instead have the very disturbing, severe allergic symptoms (anaphylaxis) that mean they must go to the hospital. He says patients with breathing problems or any other life-threatening symptoms need to seek immediate medical attention. Morris, who has had severe reactions, now carries an EpiPen with him at all times.

While Benadryl can treat the symptoms, scientists have yet to discover a way to eliminate the allergy itself. In some people, the allergy appears to go away on its own—years later, they have no detectable antibodies and can eat red meat again without a problem. In others, the condition seems to go on and on.

Taylor, who says he misses red meat at times, has tried “microdosing” by eating only small amounts of meat—but without success.

Cutting out red meat entirely is the only known cure, says Platts-Mills. The doctor has reached a final conclusion: “I am an adult, and I don’t need red meat, so I have stopped eating it.”

That can be a tough prescription. Morris, who was born and raised on a farm, says he used to eat either beef or pork “almost every night for dinner, or for breakfast. I’ve had to change my diet completely.” The other day, even a chicken casserole had him reaching for his EpiPen (it was made with sour cream and cheese).

At the clinic, his arm still dotted with red welts, Morris asked Platts-Mills what he always asks: “When do you think I can go back to eating meat?”

Platts-Mills answered with a question that was essentially rhetorical: When do you think you’ll be completely free of any exposure to ticks?

In Greene County, that won’t be anytime soon. So Morris’ girlfriend, pondering his test results, looked for a bright side. “Maybe salmon steaks?”

Additional reporting by Laura Longhine.

Deer control

White-tailed deer, the primary hosts for the lone star tick, are among the most adaptable mammals out there. Without predators, a deer population can grown by a third or more in a season, says Bob Duncan, biologist and executive director of the Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries.

Charlottesville is taking steps toward deer population control. First, it recently allowed residents to participate in the Virginia Urban Archery Season, which allows deer hunting by bow and arrow or crossbow (with the required permit).

Second, this past winter, after much debate, the city hired Blue Ridge Wildlife and Pest Management, LLC, to take out deer in city parks. Sharpshooters were brought in.

The outcome of that effort was 125 deer culled in nine city-owned parks and properties, reports Brian Wheeler, communications director for the city. Seventy-one deer were killed in Pen Park alone. The program yielded a total of 2,850 pounds of venison, which the city donated to the Loaves & Fishes Food Pantry of Charlottesville.

The City of Charlottesville plans to continue the deer-culling initiative in 2019.

Preventing tick bites

One of the best ways to prevent a tick-borne disease is to avoid getting tick bites in the first place. Here are some tips from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

• Use insect repellent. Make sure it has at least 20 percent deet (a repellent chemical, also marketed as Deet brand) or use those with picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus, para-menthane-diol, or 2-undecanone.

• Hikers, don’t go off trail. Try to avoid brush, tall grass, or tree limbs.

• Use 0.5% permethrin insecticide on clothing and gear. (Some gear comes pretreated with permethrin, but Consumer Reports found that permethrin-treated shirts were not as effective against bites as an ordinary shirt that was sprayed with deet.)

• Shower soon after coming inside, within two hours.

• Treat pets for ticks, especially dogs. Ask a vet about the most safe, effective prevention products

If you do spot a tick on your body, remove it immediately (see tips below). Kill the tick, keep it, and bring it to your doctor if you can. Remember, alpha-gal symptoms may appear hours after a bite.

Here are the CDC’s tips for how to remove a tick safely:

• Use tweezers to grasp the tick near its head or mouth and remove it carefully.

• Do not twist as you pull the tick out. Pull it straight out of your skin. If any part of the tick is still in your skin, remove it.

• Treat the tick as if it’s contaminated; soak it in rubbing alcohol.

• Clean the bite area with an antiseptic, like alcohol or an iodine scrub, or use soap and water.

• Do not crush a tick with your bare fingers (their juices can leak).

• Check daily for ticks on humans and pets when you go outdoors, especially in the following areas: ears, hairline, underarms, groin, bellybutton, paws.