As a three-year resident of Grady Avenue, I used to live right up the street from New Covenant Pentecostal Church and would drive past the narrow white structure, hearing the booming sounds from inside, wishing I was in there, too.

When I finally met Bishop William Nowell and told him this, he smiled, revealing a front tooth rimmed in gold. “Oh yeah, we get down,” he replied.

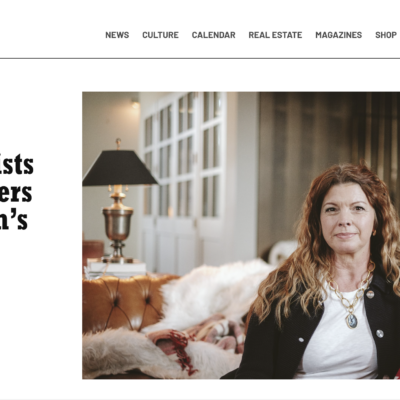

On a mission from God: Bishop William Nowell gets the band together to praise and rock at New Covenant Pentecostal Church. |

Two days after that conversation, I sit in a pew near the back of the church. Up front, three ladies stand in front of microphones. To their left, a guitarist strums, to his right a bassist and a drummer pound away. A sharp, ragged sound comes out of a large Fender amp, its source unidentifiable until I peer around the sizeable podium to see the bishop with a guitar perched on his leg.

I move up front and take a seat as the song winds down. Next it’s time for the testimonials, with the bishop continuing to pick at the guitar lightly and lovingly as church members thank God for all their blessings. Then the band starts up again, this time to the tune of “The Old Rugged Cross.” As the ladies begin to sway, the sound lurches loosely forward, led by Nowell’s bluesy guitar style, helped by the fact that his amp is cranked way up. “On a hill far away stood an old rugged cross,” the ladies begin, “the emblem of suffering and shame.” The bass player lays down a fat line that shook his Peavey amp, the drummer stumbles behind. “And I love that old cross where the dearest and best…”

I am already hooked, the ladies’ voices lifting my spirit up, the bishop’s staccato strumming rooting my feet to the earth. Gospel with a blues feel creates an interesting dynamic, a microcosm of the relationship between man and God—reality versus pie in the sky. “The blues style fits right in,” Nowell says. “It’s pretty close to gospel music anyway.”

Born in Henderson, North Carolina, the 70-year-old Bishop was surrounded by the blues as a youth. “That was the old type of music back there then,” he says. “I picked up the blues style and I even tried to play the blues. It’s a heritage I guess.”

At 18, the Bishop left home and began a musical sojourn, playing in a group called the Carolina Kings and another band called the Sammy Davis Juniors that, despite their name, played all types of music including rock. That was in the late 1960s and as Nowell witnessed the excesses of the road he began to yearn for a different way. “The lifestyle I was living got rough and I decided that wasn’t the kind of life for me,” he says. “I kept searching for a better way of life.”

Meeting his future wife—a lifelong “church girl”—seems to have been a pivotal moment for the Bishop. As he courted her, he found himself being pulled in a new direction. “I felt the calling of God,” he says matter-of-factly. “I know that sounds crazy.” Turning to the Lord also led him into a new profession.

“I found out I had a gift I didn’t know I had,” he says. “I had a gift for encouraging people and really giving words of consolation and I knew what my gifts and calling were.”

Encouragement and consolation are definitely two apt words to describe the service at New Covenant. After the three ladies finish their song, three gentlemen dressed in identical apple cider brown suits step to the front and the familiar beginning of the bishop’s playing—reminiscent of a style popularized by Fat Possum Records—starts the band in a slow, soulful beat. Then the bishop’s younger brother Joseph begins to sing, “Doctor, means so much to me.” The congregation, 40 or 50 deep, repeat after him, over and over again. I am reminded of an old Sam Cooke tune, but less polished, funkier.

Ten minutes later, the bishop stops strumming and strides to the wooden podium on the small stage. “I was thinking the other day,” he says and pauses. To his left, another one of his brothers, Robert, picks a few strings on a guitar. “Ain’t it funny how things can change overnight.”

In the early 1970s, Nowell joined some of his family in Charlottesville where he decided to start his own church, New Covenant. Over the years, his adopted home has become a center from which he spreads an influence both far and near. As members have left New Covenant to move elsewhere they have set-up branches of the church in North Carolina and New Jersey, eight in all that the Bishop supervises.

Here at home, the Bishop and his congregation regularly penetrate the community at large, from performances at the regional jail to a yearly gig singing for the Charlottesville 10-Miler (which is held in April). “They pay us every year to set up outside our church,” Nowell says. As the runners go by, the choir performs old hymns like “I Will Bless the Lord at All Times.” “That’s the particular song that they love,” the bishop says. “They request that every year.”

The Bishop and his choir have performed for the Charlottesville runners for five or six years, the same amount of time they have aired their Sunday services on local public access (channel 13). If you tune in at 8pm on Sunday night, you’ll be able to see performances like the one Nowell gave after his sermon to close the service. After calling up a member of the congregation to take his place on guitar, the bishop grabs the microphone. “In your care,” he sings in a deep-throated baritone, and the rest of the congregation falls in as the band vigorously plays. “Throw your arms around me.”