LaQuinn Gilmore felt sick to his stomach. He had not eaten enough before taking the antibiotics his doctor had prescribed him for a hand infection, and knew he needed to throw up.

While driving down Monticello Avenue on the night of January 11, Gilmore pulled over, got out of his car, and leaned over next to the vehicle. He soon saw a car pull up beside him, and a man asked him if he was all right.

“I’m thinking it’s just a concerned citizen or something, and I’m like ‘Yeah, I’m all right man. I just took some antibiotics,’” says Gilmore, a local musician. After he started dry heaving, the man repeated his question, “and I’m like hold up—this can’t be no concerned citizen.”

When Gilmore again said that he was fine, the man ordered him to get back into his car and stepped out of his own vehicle. Through the brightness of the headlights, Gilmore finally realized the man was a Charlottesville police officer.

The officer, who is white, approached Gilmore and asked to see identification. Gilmore, who felt he was being racially profiled, pulled out his phone and started recording. From there, Gilmore says the incident escalated into a violent altercation that left him with serious injuries.

A brief Facebook livestream shows Gilmore say “stop walking behind me” and “I haven’t done anything.” He accuses the officer of harassing him and claims that he knows his rights, while the officer continues to follow him down the sidewalk.

In the video, the officer orders Gilmore to calm down and put his phone away, and tries to snatch or knock down the device. When Gilmore refuses, the officer handcuffs him and the livestream stops.

While he was being pursued and detained by the officer, Gilmore says that four or five more police cars arrived on the scene.

“The way I see that they were set up, I thought they were going to shoot me,” he says.

After body slamming Gilmore to the ground, six to nine officers “jumped all over his body,” he says. Gilmore was already wearing a splint on his injured hand.

“The pressure they were putting on my body, I could feel stuff cracking,” he adds. “They were trying to kill me.” They also searched his entire body and pockets, Gilmore claims.

After seeing Gilmore’s livestream, his friend Morris Rush, who lives nearby, drove to help him, arriving shortly after the officers yanked Gilmore up off the ground.

“When I first got there, they were standing. There were several officers around [Gilmore], I would say four to five,” says Rush.

According to both men, the white officer who first confronted Gilmore then brought him across the street to speak with the shift commander, who had arrived on the scene.

“[Gilmore] was still in handcuffs and upset about what had happened,” says Rush.“I asked [the officers] was he under arrest, and they said no. I asked them why was he still in handcuffs then, so they took them off of him.”

Gilmore says the shift commander then asked him about what happened. The commander apologized multiple times, but claimed that the officer who initially confronted him was a “good officer.”

“I could tell by the officer’s body language that he was very frustrated,” says Rush. “He knew he had done something wrong.”

“The pressure they were putting on my body, I could feel stuff cracking. They were trying to kill me.

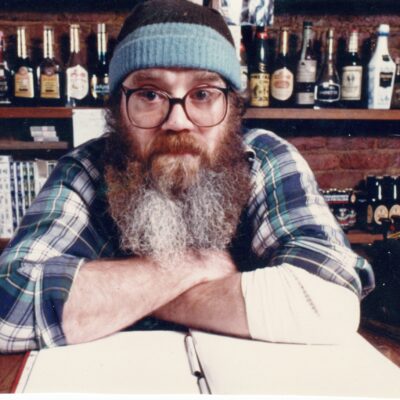

LaQuinn Gilmore, local musician

The shift commander then let Gilmore leave. He was never arrested or charged.

“I’m glad I came down there, because I don’t know what could have happened,” adds Rush.

Following the incident, Rush drove Gilmore to his house.

By the next morning, Gilmore could barely walk. He went to the emergency room, where he was diagnosed with a closed head injury, a concussion, contusions on his legs, acute bilateral lower back pain, and acute post-traumatic headaches.

Because he does not have the money to pay for rehab, Gilmore plans to do it on his own from home. He’s also had to delay a planned new album release.

Since the alleged assault, Gilmore has filed an internal affairs complaint with the Charlottesville Police Department. The department has 45 days to complete its investigation and announce its findings. If the complaint is found unfounded, exonerated, or not resolved, it can then be investigated by the Police Civilian Review Board.

According to police spokesman Tyler Hawn, the department cannot comment on Gilmore’s allegations at this time, and cannot comment on whether or not it plans to release body camera footage of the incident.

With the assistance of his lawyer, outspoken local criminal justice reform advocate Jeffrey Fogel, Gilmore plans to sue the department. He’s also started an organization called Capture Cops, encouraging people to record police activity.

Gilmore has set up a GoFundMe to help support himself and his family over the next few months.

“It still bothers [Gilmore] a lot physically and mentally. He’s still having problems with his back. He’s in and out of the hospital, taking a lot of medication,” says Rush of the aftermath. “He’s making it through, but it still bothers him.”

Correction 2/4/21 – An original version of this story said the department did not plan to release body camera footage, when in fact at publication time it had not determined whether or not it would release body camera footage.