During jury selection, the prosecution asked each prospective juror if he or she would feel comfortable judging someone, a question that’s harder to answer than you might think. It’s in our nature to judge others, their hair, their clothes, how good looking or smart they are, we judge and convict people for a million minor crimes every day. Yet we fear it as well; Judge not, lest ye be judged. Because, what if we’re wrong? Who are we to judge?

|

George Wesley Huguely V, a 24-year-old former UVA lacrosse player, is charged with first degree murder, felony murder, robbery, burglary, statutory burglary, and grand larceny, in conjunction with the May 3, 2010 death of fellow UVA student and lacrosse player, Yeardley Love. Huguely never took the stand during his trial, which ended Saturday, February 18, and he now awaits the jury’s verdict. Deliberation is scheduled to begin Wednesday, February 22. (Photo by Nick Strocchia) |

Studies show that most jurors take the job very seriously. The Huguely jurors are mostly in their 30s or 40s. A few of them have been on juries before and almost half have a connection to UVA. They’re very attentive; they lean forward and take notes. The judgment they hand down on George Huguely may not be the one he wants, but I feel pretty certain it will be carefully and fairly decided.

Closing arguments ended on Saturday. Jury deliberation begins Wednesday. The Commonwealth v. George Huguely is all over but the verdict. What that verdict will be is the big question, but there are other questions that I’ve asked myself these last two weeks, questions that may be unanswerable, but that seem vitally important.

How did Yeardley Love die?

The truth is we don’t really know.

The official cause of death was listed as “blunt force trauma to the head,” but from the beginning it was hotly contested. The defense made noise about the possibility that Love died of an Adderall-induced heart attack. The Commonwealth stuck with the blunt force trauma explanation, caused, they said, by Huguely slamming Love’s head against the wall.

By the time the trial was underway, both of these stories had basically been abandoned. Love’s Adderall prescription was brought up in court, but mostly by the prosecution, who squashed the idea thoroughly. The defense, meanwhile, pointed out several problems with the theory that Love’s head hit the wall; most significantly that the wall itself showed no sign of impact, the pictures hanging on it weren’t even crooked.

So both teams changed tactics. The defense had been pushing the idea that Love’s head hit the floor while she and Huguely were wrestling, making any resulting injuries seem almost accidental. Fine, the prosecution said, her head hit the floor, but it hit the floor repeatedly, while Huguely was smothering her with his hand over her mouth.

The medical testimony was long and complicated, and while neither side offered a totally cohesive story, the basic explanations of Love’s death are as follows: The Commonwealth says that the blow or blows to her head caused damage to her brainstem, which in turn caused her heart to stop. The defense claims that the blow to her head wasn’t hard enough to kill her, as evidenced by the lack of a skull fracture or major bruising in her brain. Instead, it was a process called reperfusion, due to the CPR administered when her body was discovered, that caused what damage her brain did have.

Instead, the defense says, she died of positional asphyxia. After Huguely left, she crawled under the covers and lay down, perhaps to try and sleep. With her breathing slowed by a blood alcohol of .14, and her face in her pillow, she suffocated to death. The Commonwealth disputes this by pointing out that she was clearly unconscious when Huguely left, or else she would have screamed or tried to go for help.

We may never know exactly how Love died. The medical evidence isn’t 100 percent certain, and the forensic examination of the crime scene is flawed because Love’s body was moved from the bed by one of the people who found her.

Only Huguely and Love were in the room that night, and Love is dead. Huguely exercised his right not to testify, so for now the only firsthand account of what happened is the rambling, drunken confession he gave the police the morning he was arrested. On the tape, Huguely says he went to Love’s apartment to talk. She wouldn’t let him in, so he kicked a hole in the door. His description of what happened is garbled, but goes something like this:

Love was sitting up and “freaked out.” They sat and talked, but then “she started getting aggressive.” He “shook her a little bit” and she began hitting her head against the wall. He kept shaking her, telling her to stop. She got up and told him to leave. He grabbed her arms and they presumably fell to the floor, where they “wrestled.” He “held her” and at some point her nose began to bleed. Finally he pushed her on the bed and left.

Who is George Huguely?

Yeardley Love was both everywhere and nowhere during the two weeks I spent covering her murder trial. I met her best friends and visited her former apartment. I got a tour of her bedroom and studied her bed. I saw, or at least heard described, her head, face, brain, and heart. But of course, I never actually met her.

George Huguely, on the other hand, was unavoidable. I watched him walk into court every day, with a blank stare and loping swagger, in too-big khakis and a blazer. He usually watched the court proceedings intently, but several times a day he would turn to his right and scan the crowd. He wasn’t looking at his family, just looking at all of us who were looking at him, as if reminding himself that this was real. Sometimes his eyes would meet mine and I was always the first to look away. It felt wrong somehow, as if I was intruding on someone’s private nightmare.

Twenty-one months ago, the story of George Huguely was the story of a khaki-clad killer, a rich and spoiled athlete who brutally murdered his beautiful and bright-eyed girlfriend. Huguely was another symbol of the evils of privilege and the moral decay at the heart of college athletics. Or something like that.

By the time the trial started, most of that had fallen to the wayside. Certainly no one in court was talking about lacrosse or prep schools as if they stood for anything sinister. The focus quickly narrowed to a young man who killed a young woman, and how, and why. In the beginning, I found myself captivated by Huguely. I felt empathetic, moved even, but I didn’t fully understand why. Partly, I knew, it was based on superficial similarities like playing high school lacrosse, but mostly it was a weird sense of identification, a game of “what if” I played during the first few days I watched him in court. Of course, it was also the first time I’d seen an accused murderer in real life, a type of celebrity I admit I have a morbid fascination with.

As the trial went on, my obsession with Huguely faded. At first he’d been a mystery, someone I wanted to understand, but the trial stripped most of that mystery away. Sadly, understanding Huguely didn’t turn out to be that hard.

George Huguely “is not complicated,” his lawyer Fran Lawrence said in his opening statement. “He’s not complex, he’s a lacrosse player.” In many ways this statement is entirely accurate. Huguely has played lacrosse at a high level for basically his entire life. I would guess that from at least middle school on, all of his friends were athletes. At UVA, Huguely lived with, partied with and dated only lacrosse players. Athletes are not necessarily stupid or uncomplicated, but dedication to a sport has a way of narrowing your focus until there’s no room for anything else.

Other than lacrosse, all we know about Huguely is that he liked to drink and chase women; testimony was plentiful about both hobbies.

|

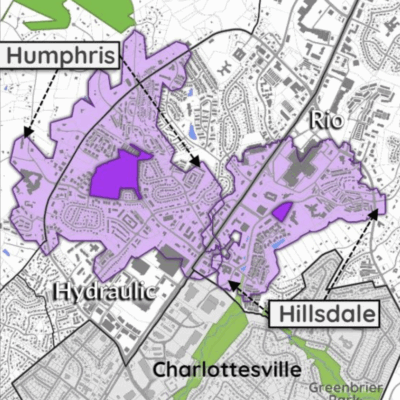

Court Square has been inundated with media teams covering the Huguely trial for the past two weeks. Thirty-five news outlets registered with the city to cover the trial, including Court TV and networks from Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Richmond. (Photo by John Robinson) |

Huguely was arrested for underage drinking in 2007, and a year later for public drunkenness and resisting arrest. By the time we get to the spring of 2010, he was showing all the signs of full-blown alcoholism.

“He’d been drinking a lot,” teammate and friend Ken Clausen testified, always on weekends, often on weekdays, and always until he was very drunk. His friends, who were also drinking buddies, had started noticing that his drinking was negatively affecting his behavior. When he drank, Clausen said, he was “more belligerent than the rest of us.”

None of his friends ever got it together enough to talk to him about his problem, but it seems to be something that Huguely was well aware of, and had discussed with his girlfriend. After the fight in February when he was found choking Love at his apartment, an incident he was too drunk to remember, Huguely wrote her a letter. It said, in part, “I cannot describe how sorry I am. I’m horrified by my behavior. I’m scared to know that I can get so drunk [that] I can’t control my life. … Alcohol is ruining my life.”

More than anything, Huguely and Love fought about other people. They both had flings, and were both very jealous. On Sunday, May 2, Huguely tried repeatedly to get in touch with three different women, texting and calling them right up to the moment he walked over to Love’s apartment to try and work things out. Ten minutes later, Yeardley Love was dead.

That’s the picture we’ve got of George Huguely: an alcoholic, womanizing, lacrosse player who killed his girlfriend. We’ve heard no testimony whatsoever that the kid had a good side.

As the trial has progressed, the amount of people sitting behind the Love family has gotten bigger. Their clothes are colorful, and the mood fluctuates between laughter and tears. The amount of people sitting on the Huguely side has stayed the same. The clothes are darker, the mood more somber. If you had to guess which group was attending a funeral, you’d probably pick the side whose child is actually still alive.

Why do we watch?

When this trial began, the national press attention was the talk of the town. Sure, people bitched about lack of parking, but for the most part, Charlottesville seemed secretly proud that it had a Media Circus to call its own. At first it was only the press and family and friends in the courtroom, but soon people started showing up just to watch.

Most spectators got up and left after two hours of talk about brain anatomy, but a few stuck it out. One older man, an ex-marine, was in court every day. During a lunch break I asked him why he was here. “Well,” he said, “I figured as much as I watched [the] O.J. [trial] I might as well see it in real life.” Courtroom dramas have been staples of our entertainment for a long time; now we just televise the real thing.

For many of the out of town reporters, this trial is old hat. They’ve covered the O.J. Simpson trial, the Michael Jackson trials, the Casey Anthony trial. In the big picture, our media event is a few tents short of a circus. Still, as the trial progressed, the courtroom got more and more crowded with UVA students, lawyers, and local business owners, everyone wanting to see what all the fuss was about.

So what was all the fuss about?

Maybe it’s the allure of real human drama, better than any television show.

Or perhaps it’s a struggle for the heart and soul of UVA, a last gasp of the elitist culture of white male privilege.

Maybe it’s another battle in a war to keep men from hurting women.

We watch because life has become an endless Twitter feed, and we’re all tourists with thinking phones. We watch because we can’t look away from other people’s tragedy. We watch because we want justice to play out in public, so that the punishment can restore order to our world.

We watch because we hope his guilt will make us feel more innocent.

/Huguley_STROCCHIA.jpg)

/RI__IMG_3413.jpg)