City Hall’s recent struggles have been well-documented. A series of high-profile positions have gone unfilled for extended stretches, and councilors have publicly clashed. Those challenges have prevented the city from carrying out one of its main duties: fully supporting its boards and commissions.

Charlottesville’s Human Rights Commission and Office of Human Rights, a volunteer board and a paid city office tasked with investigating complaints of discrimination, have been particularly affected, say group members.

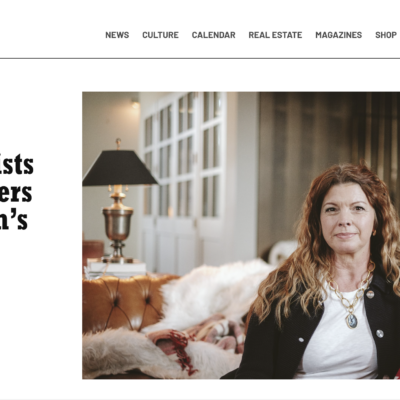

“The work of the Human Rights Commission has not been in any way a priority for City Council or other offices of the city,” says Kathryn Laughon, who has served on the commission for two years. “For a year, we’ve had no director…and our work has essentially been put on hold. There’s this domino of [city] appointments that need to be made, and a sense that we should not move boldly forward until all these pieces are in place.”

Charlene Green stepped down as OHR director last February, and for the last year the office has been run entirely by outreach specialist Todd Niemeier.

Since their inception in 2013, the organizations have been a source of debate for commissioners, community members, city councilors, and city staff, who have different ideas about how the office and board should be structured, and what kind of resources the organizations need. Those debates continued last week, as council passed a new set of rules for the commission with some controversial clauses.

The revisions align the commission with the newly passed Virginia Values Act, giving the OHR and HRC significantly more power. The organizations are now allowed to investigate complaints of discrimination based on income, as well as complaints from larger companies.

Mary Bauer, the chair of the commission, encouraged the councilors to approve the revised ordinance in order to allow the OHR to move forward with three discrimination cases that fell under the new protected classes granted by the Values Act.

However, the final revised ordinance approved by City Council during its February 1 meeting included multiple changes that were not suggested by the commission.

“The process was not great or transparent,” says Bauer, who became chair of the commission this year. “There were changes made the Sunday before the City Council hearing on which it would be voted upon…And the commission, although they saw the changes, didn’t have time to come together as a commission to evaluate them.”

The work of the Human Rights Commission has not been in any way a priority for City Council or other offices of the city.

Kathryn Laughon, human rights commission member

The last-minute changes, which were adopted from a letter co-signed by a collection of social justice organizations in town, include reducing the commission size to nine members, requiring the OHR director to have legal and civil rights credentials, and mandating the director to seek workshare agreements with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“I worked really hard talking to a number of different people about what the core of the matter was with those changes, what were the fears those changes were addressing. I also made sure those changes were doable,” says Vice-Mayor Sena Magill, who has worked with the commission during her time on council.

“If we identify unintended consequences down the road, we will probably just have to change the ordinance again,” she adds.

Community advocate Walt Heinecke, who has continuously advocated for the changes listed in the social justice groups’ letter, says he understands the commission’s wariness specifically towards the requirements for the new director, which some fear will restrict people of color from applying. However, he believes it is important to hire an attorney for the position to “[signal] to employers and landlords in the community that this is serious business.”

Shantell Bingham, the former chair of the commission and a current member, was also disappointed by the lack of transparency in the revision process, but says she’s proud of some of the work the commission has done in the last few years.

While many other commissions are majority—or all—white, the HRC is now one of the most diverse.

“I am very, very proud of us being able to have more people of color, more transgender people on the commission, more people who are exactly what the ordinance says it’s meant to protect,” says Bingham.

The commission also drafted recommendations for the Charlottesville Police Department on how to improve its practices and policies. “We were never able to actually meet with anyone with the city to discuss the work that we did—but that work was done,” says Laughon.

Last year, the commission passed a resolution in support of a local eviction moratorium, and took a stance against the University of Virginia’s decision to bring students back to Grounds last fall.

And since multiple commissioners spoke out last year about the need for direct contact with a city representative, at least one City Councilor has attended the commission’s monthly meetings.

“[This] has significantly helped,” says Bingham. “But there’s still a lot of work to do with transparency, with the working relationship between the Human Rights Commission, city management, and City Council.”

According to Magill, council recognizes the dire need for a new director, and the many challenges it has brought. Under new City Manager Chip Boyles, staffing changes are expected to come soon. “We’re going to have to give him a little bit of time, especially as we’re right in the middle of budget season,” she says. “[But] we know the position is sitting there and needs to be filled.”