Charlottesville has its share of decades-old businesses that are locally owned and operated and insinuated into the fabric of the community. Unfortunately, in the coming weeks, it will have one less.

The owners of Reid Super-Save Market, a popular grocery store on Preston Avenue, announced January 6 that they have accepted an offer from local nonprofit thrift store Twice is Nice to consolidate its two Preston Avenue locations into Reid’s current building after the market closes on January 25.

Reid’s has been a Charlottesville fixture since shortly after its namesake, Malcolm Reid, bought out the Stop and Shop’s West Main Street location in 1961. When a fire forced a move to Preston Avenue in 1982, Kenny and Phyllis Brooks purchased the business from the Reids after Malcolm’s passing. In the 43 years since, it has been popular with residents in both the 10th and Page and Rose Hill neighborhoods for its proximity, and with those from around the city and beyond who wanted to support one of Charlottesville’s few locally owned and operated grocery stores. In 2016, it passed from Brooks to his daughters, Sue Clements and Kim Brooks. Their tenure as owners started just in time for COVID-19, which is when the store’s struggles began.

“The grocery business is a very low-margin business,” Clements says. “‘A penny-making business,’ as my dad used to refer to it.”

Reid’s problems went beyond the pandemic, however. While COVID changed many people’s shopping habits, Clements says the combination of increases in the cost of goods and services, rising instances of theft and shoplifting, and the cost of living in Charlottesville all caused her store to struggle. The final straw, it seems, was inflation.

“Increased prices and inflation [had] a huge impact on our business,” Clements says. “As consumers started to watch their expenses, many would opt for a big-box store with lower prices, prices that an independently owned store cannot compete with.”

Reid’s got a lifeline in January 2024, when Megan Salgado, a customer and Charlottesville resident, started a GoFundMe to keep Reid’s from closing its doors. The effort raised $21,370 from community members and other local businesses, but Clements knew then the lifeline wouldn’t keep the store afloat permanently.

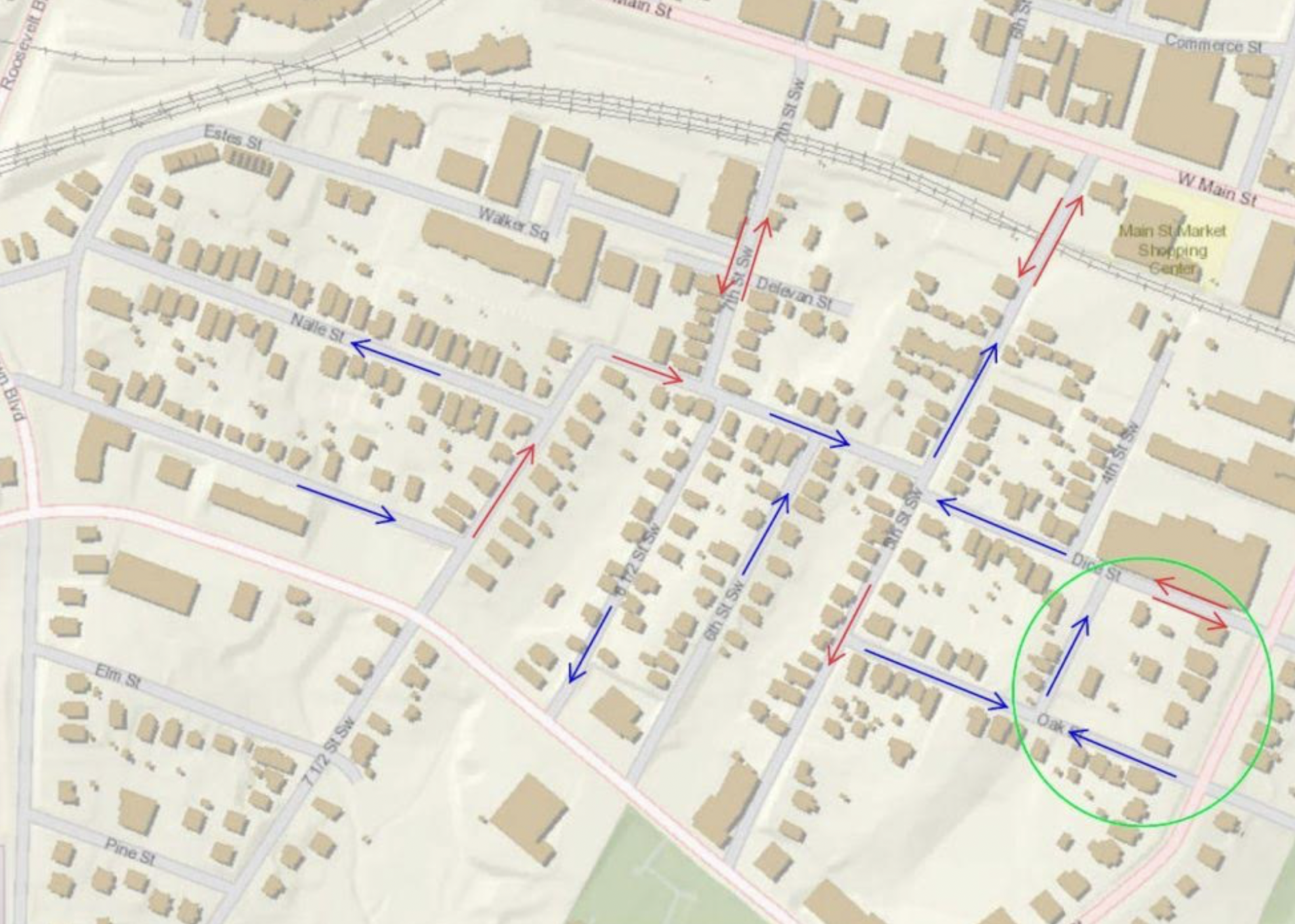

Reid’s closure comes at a time when grocery stores in downtown Charlottesville are at an all-time low, and stores like it are becoming a thing of the past. The term “food desert” was coined in the U.K. in the 1970s to describe areas where low-income residents were unable to access adequate nutrition because of a “perfect storm” of issues that restricted their ability to acquire and afford fresh food. Now, the USDA uses the term to refer to areas where a majority of the residents are low-income and have low access to healthy food, defined as more than one mile from a source of fresh, nutritious food (i.e., grocery stores, farmer’s markets) in urban areas, or 10 miles in a rural area.

According to a map on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s website based on 2019 data, large swaths of the 10th and Page and Fifeville neighborhoods are currently designated as food deserts, with almost the entirety of the remainder of downtown Charlottesville on the threshold of the same designation prior to Reid’s closing and the loss of other locally owned stores like the Kim IGA on Cherry Avenue, which community leaders have focused on reopening, as reported in a C-VILLE cover story last fall.

Kennedy Smith, a senior researcher at the The Institute for Local Self-Reliance, suggested in an October 23 column for the Richmond Times-Dispatch that the failure of local, independent grocers like Reid’s might be more than the will of the free market; she suggests the game was rigged from the start.

The closure of Reid’s next week is a loss for the little guy—and for residents who have relied on the locally owned grocery store for decades. Photo by Eze Amos.

“Independent grocers are failing, not because they can’t compete with the bigger chains on service,” Smith wrote. “It’s because those chain retailers have been allowed by lax antitrust enforcers to bully their suppliers into exclusive deals. Those suppliers, squeezed by powerful retailers, then try to make up their lost profits by overcharging independent grocers for the same goods.”

Smith suggests the Regan-era rollback of the Robinson-Patman Act rigged the system in favor of large corporations, allowing chain stores like Walmart and Food Lion to get food at prices that smaller stores like Reid’s cannot. According to Clements, the increased cost of goods and services reached “the point that we could not be competitive if we had passed all of those along to our customers.”

Reid’s loss is Twice is Nice’s gain, however. The thrift store’s business model is centered around a mostly volunteer staff and donated goods, enabling it to donate a reported $2 million to area seniors over the last decade. Operations Manager Lori Woolworth says they’re sad to see Reid’s close, but excited about the opportunity to grow.

“Remaining in the city, serving the neighborhoods we currently serve, offering a local and affordable shopping option has always been important to us,” she says.