It was 1996, and inside Charlottesville’s Outback Lodge, Howard Herz was preparing for one of the hundreds of shows booked and mixed there by the late, beloved sound engineer Terry Martin.

Herz went to bouncer Bill Tyler and told him that Martin’s new guitar act, a guy named Derek Trucks, was here. He was Butch Trucks’ nephew, and said to be the reincarnation of Duane Allman, so Tyler had better go tell those kids playing foosball to clear out so the Outback could set up for the band.

When Tyler returned, the miniature soccer match hadn’t slowed. He told Herz they had a problem. “Why’s that?” asked Herz. “Because that’s the band,” said Tyler.

A decade and a half later, that teenage foosball player would win his first Grammy as the head of The Derek Trucks Band. Thanks to Martin, who passed away unexpectedly at the end of July, the Outback Lodge was home to one of the band’s earliest shows.

“It was a tiny little place, and some bands would show up and be like, ‘What the hell is this?’” says Herz. “Then they would meet us and they would meet, more importantly, Terry…and the looks on the musician’s faces when they heard the mix coming through the monitors, or saw the reaction of the crowd or how professional he was, was really something special.”

Everyone from Allman Brothers Band guitarist Dickey Betts, to Buddy Miles (a drummer and Jimi Hendrix collaborator), to Dave Matthews Band guitarist Tim Reynolds, would walk into the Outback Lodge and ask for Martin.

The venue hosted The Seldom Scene the evening after the band played at the Kennedy Center for Bill Clinton. “The next night, they’re at the Outback, back behind the gas station in a roadhouse with no windows,” says Herz. “People in the crowd are handing them shots on stage and they’re drinking with the crowd after they just hung out with the president the night before. Honestly, I think they were happier at our place.”

Sound studios around Virginia sent fledgling bands to the Outback to get their “live feel” with Martin at the mixing board, propelling the Lodge—and Charlottesville—to a new level of recognition as big names began drawing large crowds to the Preston Avenue club’s cramped interior.

“Those guys wouldn’t have played the club if it wasn’t for Terry being there,” says Herz. “They could have played a lot of places in town. They came there because Terry was there.”

That talent and charisma is something that lifelong friend Tyler always saw in Martin, beginning when he was an 18-year-old building a hot tub in the bed of his truck to drive girls around in between DJ gigs at the Days Inn on Emmet Street.

“He wanted to be a trendsetter,” says Tyler, who followed Martin to his most recent job at IX Art Park. “He didn’t want to play one genre…he didn’t just want to be a hip-hop DJ. He didn’t want to be a disco or country DJ. He wanted to be a DJ of the people.”

Loved by drummers and bass players for his low end-heavy mixes, Martin was famous for what Jeyon Falsini, who helped Martin book bands at the Outback, calls “the shortest, most concise, fastest sound check you’d ever heard.”

“He held artists to a pretty high standard,” says Falsini. “No matter what genre of music you play, he always had some advice. I think if you talk to any musician in town, you’d find something that Terry told them to do that ended up working out really well for them. That’s probably one of his greatest legacies.”

On the other side of the mixing board, Martin shaped the lives and careers of everyone from Falsini, whose club, The Ante Room, he helped name, build, and sound engineer, to Burley Middle School instructor Ivan Orr, the vocalist and saxophonist for a local go-go band that Martin reunited.

Originating in the late ’80s from Charlottesville High School’s pep band, the disbanded Ebony Groove started discussing a potential reunion in 2008—but it wasn’t until 2018, when Orr mentioned it to Martin in passing, that Martin made it happen. He arranged a gig at IX, then stood behind the mixing board as hundreds packed the audience for Ebony Groove’s Alumni Weekend concert.

“Their very first show, that just blew minds, man,” says Falsini. “Terry built them from the ground up, got these guys back together, got them practicing, then unveiled them to Charlottesville and just packed the house.”

Go-go wasn’t the only genre Martin blew minds with. A veteran of everything from bluegrass to reggae to rock to opera, Martin was always willing to twist knobs for new genres. Orr and Martin even had plans for an upcoming gospel show at IX.

“A lot of opportunities I had to play music that I enjoy—funk, R&B, go-go—would not have happened without Terry being an advocate for booking that type of music,” says Orr. “Part of his legacy was about inclusiveness and diversity of sounds and people.”

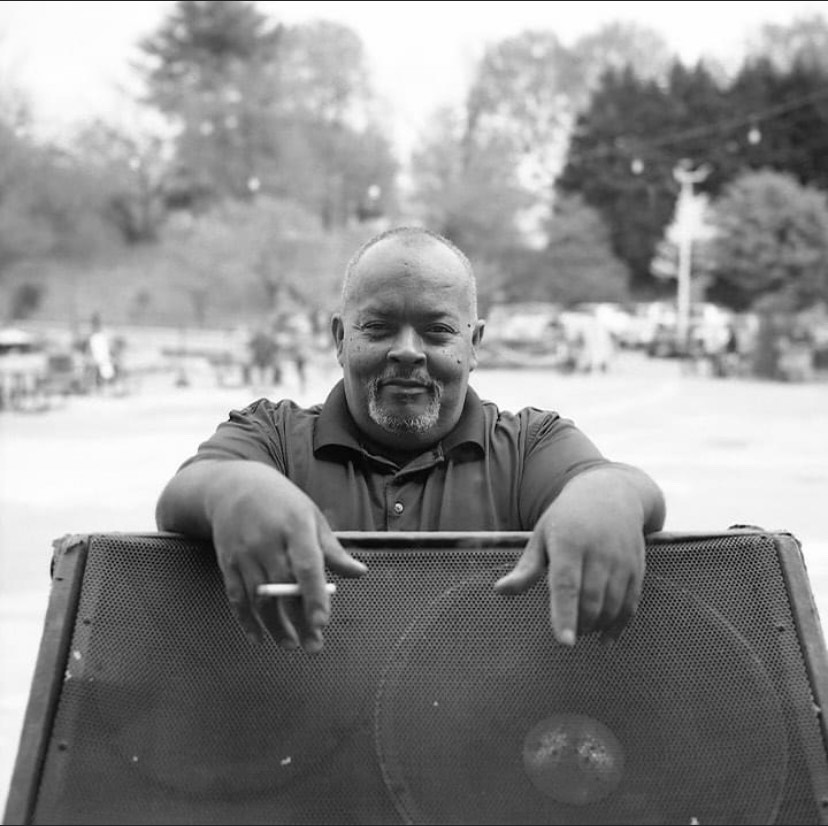

While his loved ones mourn the loss of the man with the infectious laugh, who won the lottery twice and shared stacks of the winnings with friends and family, Charlottesville’s music lovers will grieve for an architect and core member of the city’s variegated live concert lineup.

“He was such a deep part of the scene,” says Herz. “What he brought to the table was so multifaceted and complex from a personal, social, musical, technological standpoint, that I just don’t know if there’s ever going to be another him.”