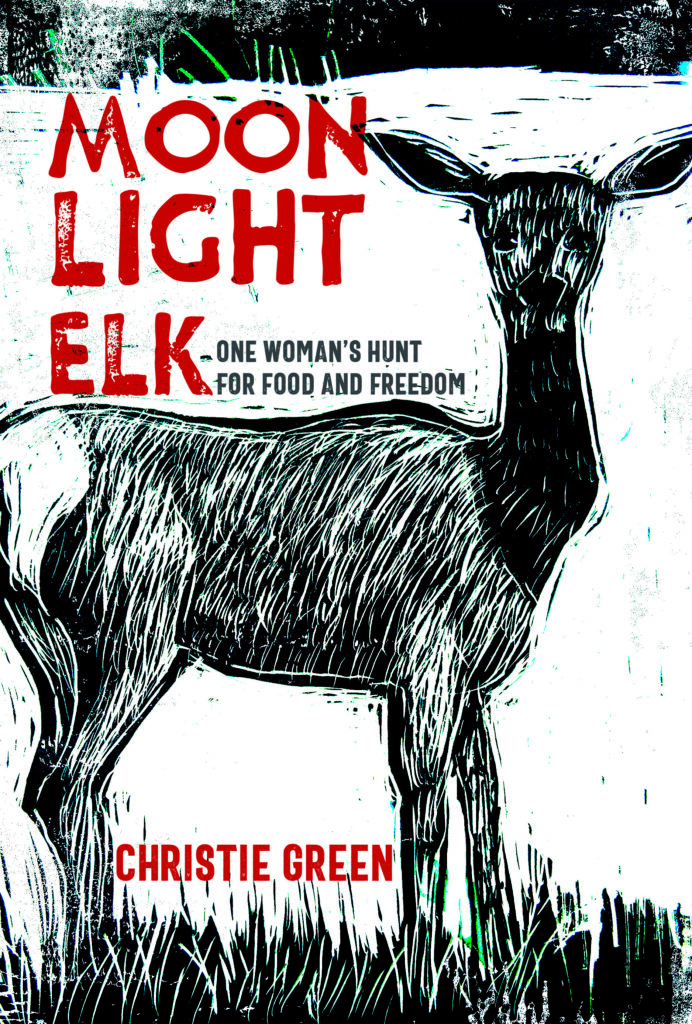

In her book, Moonlight Elk: One Woman’s Hunt for Food and Freedom, Christie Green writes: “When the days are distilled into life and death moments and attuned to tiny toenail prints in the soil and subtle wind shifts, my old identities pale.” A sensuous exploration of the animal world and our place within it, Green’s debut weaves together memoir, moon phases, and meditations on the sublime, as she examines what was involved in her decision to become a hunter and how the hunt continues to change her.

At a time when the decision to opt out of global food supply chains is a political choice as much as a financial necessity for many, Green’s book offers an insightful and reverent examination of what it means to add hunting as a locavore food source. Making the decision to take up elk hunting as a single mother working to provide food for her daughter, she writes, “Rationale named food, sustenance, and self-reliance as justification to learn to hunt… I validated my urge to hunt as an extension of practical agency.”

After beginning to hunt in 2010, Green found the act itself transformed her. And as it did so, she witnessed her motivations and self-knowledge evolve in kind. She writes, “Elk. Deer. Oryx. Turkey. Grouse and quail. By penetrating their bodies with bullet and knife as enigmatic communion through blood, guts, hide, and hoof, I began to see myself. Like them: uncontrollable, unknowable, and valuable… as is. What I sought from these animals was food. What I have found is freedom.”

During a recent interview with Green from her home in New Mexico, she reflects, “I have so many mixed emotions, and there were certain hunts that were so cathartic. … More and more, I feel less and less sure, and committed to killing. It’s very hard for me to kill, [though] I love the hunt and I love the process of being with the bodies and the animals.” At this point in our call, she turns her laptop around to show the partial skeleton of an elk she hunted last fall, hanging like a wind chime on her porch. Except that’s not right, not exactly. A wind chime isn’t revered like this. This is more like the whale or dinosaur bones one might see at a museum, lovingly reconstructed and glorified through the act of witnessing and living within their awe. Green has also photographed the animals she hunts, chronicling their inner workings as a form of appreciation.

She writes tenderly of these moments she shares, this communion with her dead: “I trace my hands along [the elk’s] muscled flanks, sinewy forelegs, plush white belly, and bend my nose to her hide, inhaling every inch of the body that will soon become the material of muscle that feeds us.” These are acts of devotion as much as anything. In our virtual meeting, Green says, “I love the body part, the food part, connecting with the animals, but I don’t know. I just learn more and more every time and I’m wondering about going and being with the animals without killing them.”

Green was raised in Alaska, and her professional background as a landscape architect and artist informs her writing. But her dreams exert a significant influence as well. As we talk, she shares that interaction.

“I work every morning with my dreams,” Green says. “Even when I’m hunting, I get up two hours early, and sit in that liminal darkness, and write, and draw, no matter what. A lot of times, those dreams will inform the hunt. I absolutely abide by them, no matter what. I feel like the psyche—in the form of dreams and images and language—can get at something so powerful.”

Indeed, when writing the essays that would become Moonlight Elk, Green recalls, “I had this dream that said, in a nutshell, ‘You must write in the same way that the elk run up the hill to save their lives.’ In other words, it was like I had to write to save my life. … Every essay came from an experience of hunting and reflecting.” After writing 20 or so essays, Green shared that work with an editor in 2017, who supported her in transforming the collection into Moonlight Elk. Green has also committed to writing two additional books for her publisher in the next couple of years, which promise to continue her thoughtful exploration of our relationships with the cohabitants in this world.

“My whole intent is to inspire reverence for and stewardship of the Earth,” Green says. “How can we open ourselves up enough to feel that there is no other, no separation? We are all direct extensions from the Earth. The hardest part was trying to put into language my feelings, and this urgency to care, and connect, and be stewards. … It’s really hard for me to be around humans who believe that we’re the ones who should and do rule and that everything is for our sake, or that we’re entitled to any of it. I just don’t believe that. I believe we can be a lot quieter.”

Christie Green will read from and discuss Moonlight Elk: One Woman’s Hunt for Food and Freedom, with Erika Howsare at Bluebird Bookstop on April 17. Photo: Anne Staveley.