For about six years, Alasdair MacLean has been writing a novel.

“Occasionally I’ll send a draft of that to my agent and have it thoroughly rejected,” MacLean laughed when reached at his home in London. “And then I’ll start again. And that’s kind of been it for six years.

MacLean’s novel is about growing up in the suburbs of southeastern London in the 1990s—“Which, coincidentally, I did,” he said.

And the southeastern London suburbs, coincidentally, defined the earliest songs of The Clientele, the quintessentially British indie-pop band MacLean co-founded in 1997.

“It’s turning into a bit of a life’s work,” MacLean said. “Which is a bit tragic, really. It’s an odd thing to base an aesthetic on, I suppose.”

Save for a few scarce dates, The Clientele (pronounced CLEE-un-tell) has been largely inactive since 2011, when the band went on an indefinite hiatus. But it’s reuniting for a week-long tour centered around the Merge 25 festival, which celebrates the vaunted North Carolina indie label’s 25th anniversary.

Merge released all five of The Clientele’s full-length records, and in May reissued the band’s debut, Suburban Light, as part of a yearlong series which has also reintroduced notable records like Richard Buckner’s debut Bloomed, Lambchop’s critical opus Nixon, and a career-spanning anthology by seminal New Zealand indie rock band The Clean.

“I was really flattered,” said MacLean about the reissue. “There are so many great records in the Merge back catalogue, and the fact that they chose one of ours was incredibly flattering.”

Released in 2000, Suburban Light was meant to be a high-production debut rendered in a major studio, the inevitable delivery on the promise of the band’s run of critically acclaimed seven-inch singles. There were plans for string quartets, brass sections, and choirs. There were grandiose wall-of-sound production ideas—like “Martin Hannett crossed with Phil Spector,” MacLean said—and warm, vintage tones.

But it was the late ’90s in England, and recording engineers were more interested in the production style of Radiohead’s OK Computer or the Britpop dominating the charts at the time—music, MacLean said, “that was really inimical to how we wanted to sound.”

“Every time we went into the studio we said ‘This is going to be the time when we start to sound contemporary; we’re not going to sound like a ’60s band any more.’ And then we always fucked it up,” Mac-Lean said.

Instead of finding its sound, The Clientele found frustration. Eventually, the group went back to the relatively primitive but especially intimate recordings found on its demos and 7″, tracks cut wherever its members lived and whenever they wanted.

“We used those because they had a kind of magic to them that nothing else we recorded did,” MacLean said. “It was that simple. There was no further thought or ideology than it [the studio versions] sounds like shit, let’s not use it, you know?”

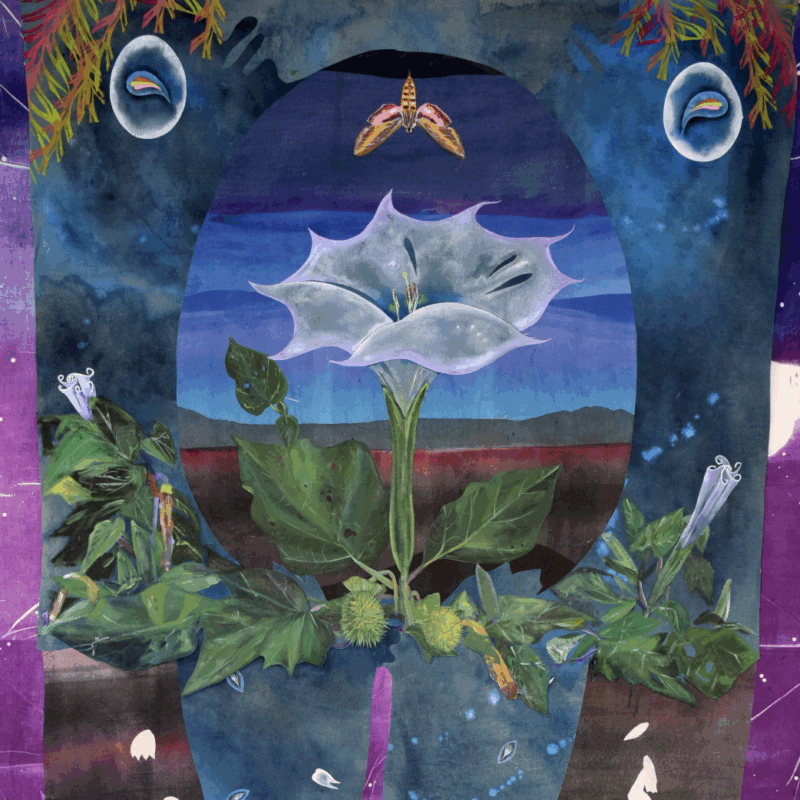

Suburban Light, either in spite or because of its low fidelity, is unfailingly gorgeous, marked by shimmering mystery. Like the artist Joseph Cornell, the titular subject of one of Suburban Light’s most memorable songs, The Clientele distills its source materials into something uniquely and instantly its own, in large part because of the band’s suburban surroundings.

“It’s an unlikely source of inspiration, I suppose,” said MacLean of the southeast London neighborhood that birthed and informed The Clientele. “I think what probably connects British suburbs is just boredom, really. That’s the aesthetic. It comes from boredom.”

But what is it composer Erik Satie said about boredom? That it’s potentially mysterious and profound? And The Clientele wasn’t just channelling ennui, they were living it.

Though it’s made up of odds and sods, Suburban Light nonetheless evokes a complete, cogent world, painting a soft-focus picture of British suburbia. MacLean’s vocals, drenched in faraway reverb, evoke the ghostly halos that surround streetlights in twilight. The marriage of grace and tension in his and Innes Phillips’ guitar playing is filled with young adult languor. The steadily pattering drums invoke the gloomy rain frequently referenced in song titles and lyrics. The negative space employed by the trio’s sparse arrangements conjure images of empty football fields and dimly lit city scenes.

“We just wrote about the things that were around us,” MacLean said. “There was woodlands and…long avenues with streetlights that stretched out from the motorway and there was the sound of the motorway and the hum behind everything else at night. For me, it’s a very poetic, beautiful landscape, and that’s what we lived and breathed in the days that we were writing those songs. And that made a lot more sense. I mean, who needs to hear another song about London? Who needs to hear another song about New York? I think we need to explore these more liminal spaces.”

Though The Clientele went on to crank out high-production records, they never quite inhabited a clearly defined sonic world. It’s a little strange for MacLean, now 40, to revisit that world. “When I was 18, I was like, ‘If I don’t leave this place, I’m going to kill myself, if I don’t get out to college or to London or a job or something,’” MacLean added with a chuckle. “So it’s kind of weird to be celebrating it 15 years later. It’s one of life’s ironies, I guess.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lo5gbXzrV0A