With the current glut of superheroes, franchises, and remakes at movie theaters, a film like Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza stands out by default simply for being low-key, unpredictable, and featuring normal- looking people. It’s also low on narrative cohesion and depth, and still sticks out. In short, Licorice Pizza is enjoyable with a strong cast, and well worth seeing, but what’s it really about? The overriding answer: P.T.A. loves L.A.

Anderson’s films overflow with adoration for his native Los Angeles—usually, the San Fernando Valley—and its people, from Boogie Nights’ porn stars to Inherent Vice’s stoner beach bums. That deep affection shines through in every frame of Licorice Pizza, this time through an exuberant, youthful lens.

This warm re-creation of the Valley circa 1973 nicely evokes the era’s look, feel, and looseness—of kids being kids, and adults usually behaving more juvenile than the children. (Licorice Pizza would pair well with Michael Ritchie’s The Bad News Bears.) Anderson captures the uniquely surreal nature of the Valley’s deep ties to “The Industry,” where seeing aging movie stars or the Batmobile is humdrum stuff.

The film’s nominal plot follows two kids seemingly as incongruous as the film’s title: 15-year-old inveterate hustler Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman), and Alana Kane (Alana Haim), an aimless 25-year-old spitfire. Gary pursues Alana even more fervently than his endless money-making schemes, and the story finds the pair roaming from one bizarrely comic, sometimes poignant, episode to the next, punctuated by their mercurial reactions. There are period trappings everywhere—Nixon on TV, Todd Rundgren on the radio, hideous wallpaper in the living room—but this appropriately funky window dressing never overwhelms the cast.

American cinema of the 1970s is another trademark of Anderson’s vision. He has so superficially assimilated Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese, and Hal Ashby’s works that he can conjure their films’ look and feel without being openly derivative (although he does lift a scene from Taxi Driver, and also draws on Clint Eastwood’s Breezy).

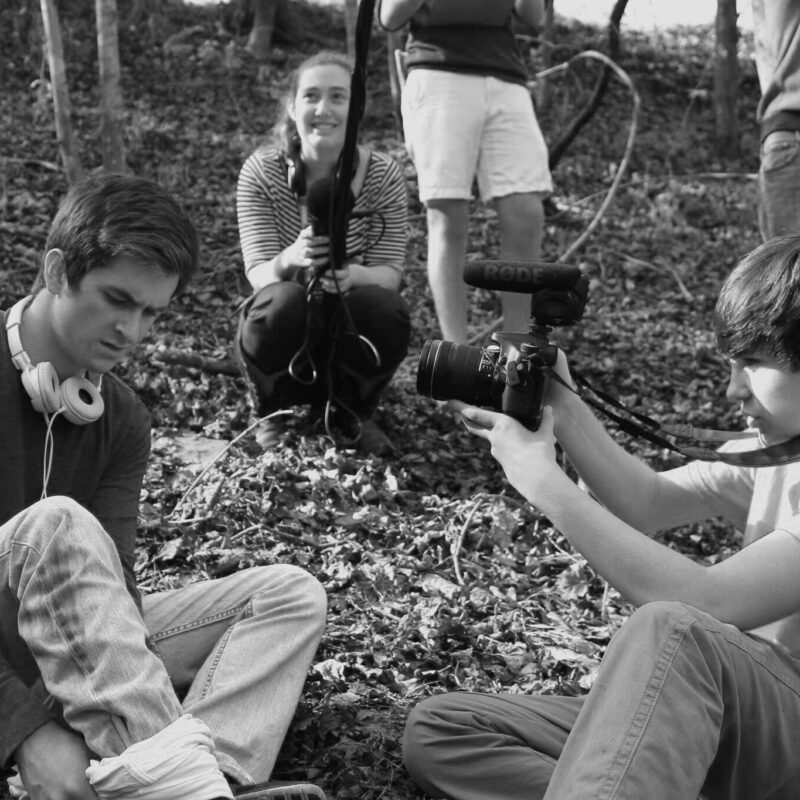

Altman’s influence on Anderson can be seen in his excellent ensemble casts, and Anderson’s latest is no exception. Hoffman and Haim are endearing. The supporting cast shines, particularly Harriet Sansom Harris as a chain-smoking agent. Sean Penn’s scenes as aging action hero Jack Holden, loosely parodying William Holden, is Penn’s best, funniest work in years. Bradley Cooper as hairstylist Jon Peters is a hilarious caricature of that era’s machismo, complete with a caveman’s hair, beard, and attitude. And the cast members who deserve special praise are the many child actors, who appear effortlessly natural and unforced.

What does it all add up to? It’s an undisciplined, arrhythmic film, and essentially just Anderson having a blast taking a sentimental journey. It’s not deep and it’s 20 minutes too long (like most current movies). But it succeeds as a light, laconic, funny film—the key word here being light—that hearkens back to 1970s filmmaking, but doesn’t equal the richness of that decade’s cinema.

Licorice Pizza

R, 133 minutes

Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, Violet Crown Cinema