Director James Hawes’ One Life does justice to the moving, true story of modest World War II hero Nicholas Winton, a London stockbroker who rescued hundreds of children from the Nazis.

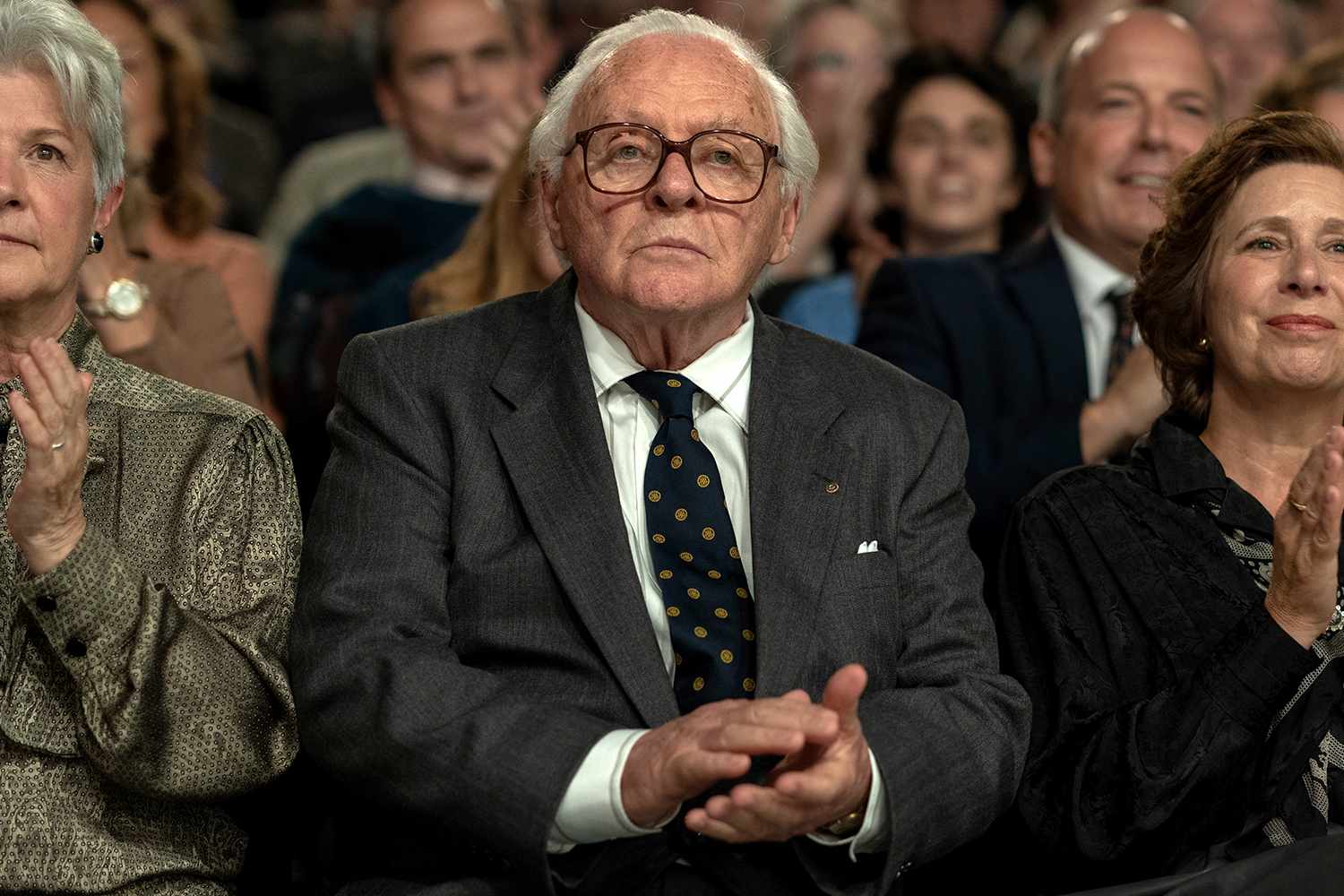

Based on the book, If It’s Not Impossible… The Life of Sir Nicholas Winton, by his daughter Barbara, the film is deeply compelling, even for viewers familiar with the details, and Anthony Hopkins gives an excellent, low-key performance as the elderly Winton.

One Life opens in 1987, and finds Nicholas cleaning out his cluttered office and contemplating the disposition of a special pre-war scrapbook. He flashbacks to the months prior to the Nazi invasion of Poland, when a younger Winton (Johnny Flynn) spearheaded an effort to help endangered children in Czechoslovakia—many of them Jewish—escape the Nazis.

Initially met with indifference, Winton and his mother, Babi (Helena Bonham-Carter), navigate choppy bureaucratic waters in England, and the Nazis’ ever-tightening hold on Europe, to place kids with British foster families. Ultimately, their efforts saved 669 children from concentration camps.

For the next four decades, Winton seldom spoke of his herculean efforts. Then he appeared as a guest on the British TV series “That’s Life,” where—in an extraordinary television moment—he was reunited with dozens of the people he had saved.

One Life will undoubtedly draw comparisons to Schindler’s List, but it differs significantly in scope and tone. Filmed in about six weeks on a modest budget, it concisely dramatizes Winton’s crusade. Rated PG in America, the film doesn’t sugarcoat its story, but also isn’t particularly graphic. Hawes seldom shows the Nazis themselves on screen, but their presence is disturbingly and effectively felt throughout the European sequences. The story’s intense moments are told in closeups of human faces: desperate children in refugee camps or the expressions of Winton and his colleagues as they try to save those kids.

A major reason One Life is so winning is its Capraesque faith in the nobility of decent everyday people. As young Winton and his team plot their rescue mission, they envision an “army of the ordinary” aiding them, which they find in British foster parents and others who guide the youngsters to safety. Stories like this on film are hard to pull off without becoming dully maudlin, which One Life manages to dodge.

The cast is first-rate led by Hopkins, Bonham-Carter, and strong supporting actors including Lena Olin and Jonathan Pryce. As the younger Winton, Flynn seems to have studied Hopkins’ earlier movies to get his mannerisms down, but avoids slipping into a caricatured impersonation. Zac Nicholson’s cinematography and Lucia Zucchetti’s editing is tight, sharp, and straightforward. Production design by Christina Moore, and costume work by Joanna Eatwell are also very good. That the film was made relatively quickly and inexpensively makes it all the more impressive.

Inspiring true-life stories can easily get saccharine, but One Life is an unpretentious and well-told film. It’s also a stark reminder that youngsters in refugee camps aren’t a thing of the past. We need fewer movies about flying people in capes and more about real superheroes like Nicholas Winton.