art

In Cecil McDonald’s photographs, the opposite of documentary is ambiguity. The wall text at his Second Street show describes his project as an alternative to the common representation of African-American families in gritty, chaotic documentary photos; instead, McDonald carefully stages his images, using himself and his wife and daughters as actors in imaginary dramas. What’s impressive is that, although every detail of these scenes is deliberately chosen, the photos are still steeped in uncertainty. McDonald’s hand, though much in evidence, is not a heavy one.

Perhaps that’s because he allows his cast members to improvise somewhat within given parameters. Take "Afternoon Picnic," in which the two girls and their picnic blanket are a fragile island of domestic order against a backdrop of anonymous industry (grain elevators, a freight train and untended grass). The image is already powerful in a design sense, but what makes it emotionally arresting are the girls’ expressions—fleeting and unreadable, perhaps registering discomfort. The open questions those faces raise would have been impossible to plan.

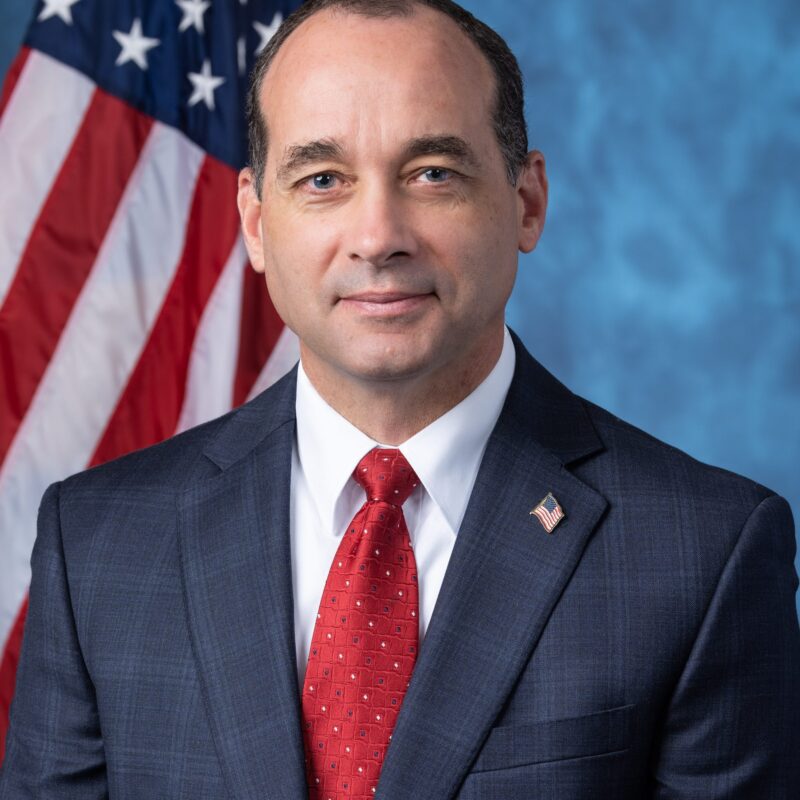

Improv caught on film: Cecil McDonald, Jr.’s photos at Second Street Gallery make for a curious collection of controlled experiments in family drama (pictured: "Shaft"). |

The possibility of really knowing this family through these photos is tantalizing, but just out of reach. If the human interactions are allowed to be serendipitous, the physical surroundings that, in documentary work, might illuminate them instead seem as orchestrated—and thus as artificial—as theater sets. "Why Scales Matter?" is shot in a living room, with McDonald and one daughter at an upright piano. She lies, maybe sullenly, on the piano bench; her father’s face is neutral; her sister is coming through the doorway. Telling details are here—sheet music, family photos on the piano—but there is a sense that even the rumpled rugs were placed just so, and that other objects may have been removed.

Though the lighting is clear and crisp, the situation is hard to grasp. And though the actual family members are present, their private life is hidden. These are productive tensions, artful rather than confused. One might equally praise McDonald’s narrative imagination and rich, muscular sense of color; but in the end, it’s the question of what it means to stage one’s own home life that drives these intriguing works.

A video of a conversation with Leah Stoddard about McDonald’s work. |