Bernard Frischer spends most of his life living in—to borrow a line from Stevie Wonder—a pastime paradise. As I sit across from him at the foot of a 20′ projection screen, I can’t help but think that he’s a spittin’ image of the Motown recording artist, wearing dark virtual reality glasses, bathed in colored lights and smiling with glee.

"This is the first time I’ve driven this thing in stereo optic vision!" exclaims Frischer, as he controls a three-dimensional simulated landscape via wireless keyboard. We’re in a conference room of an office on the Downtown Mall, but before me is Rome circa 320 A.D. I’m wearing stereo optic glasses too. "We set the time of day to 10 in the morning on September 21," explains Frischer, who looks like Mothra looming in front of his miniature world.

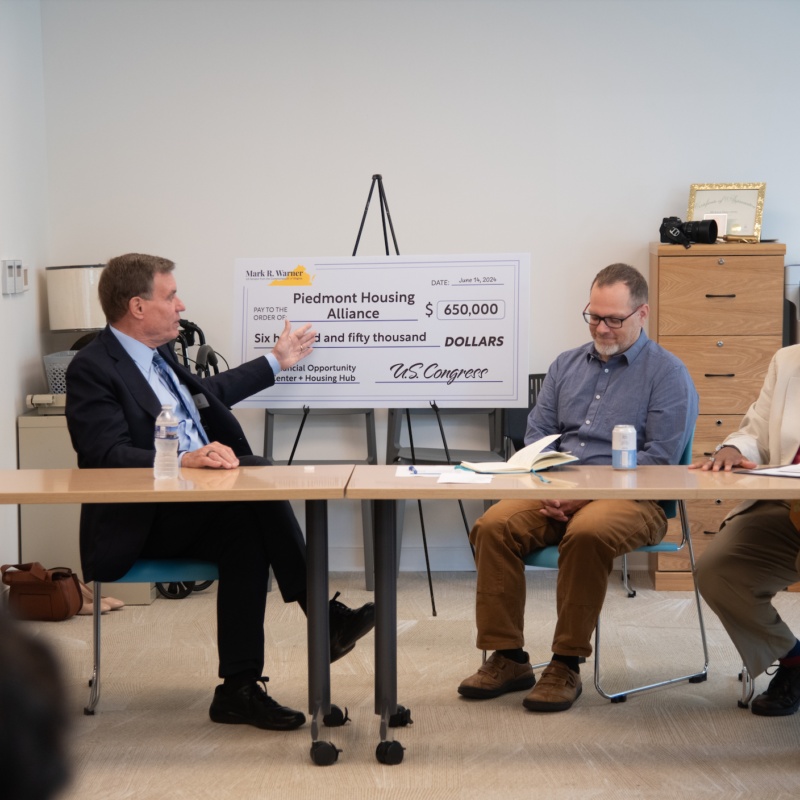

Bernard Frischer, right, with fellow researcher Dean Abernathy, says their virtual Rome acts as "a new kind of peer-reviewed journal," allowing classics profs to map out the minutest details of the ancient city. |

The miniature world quickly becomes life-size, though, as the UVA classics professor zooms us in to ground level. We examine the fluted columns of the Colosseum in exquisite detail. With another tap of a key, a Google Earth interface pinpoints our faux location on an ersatz globe.

This surreal experience is the fruit of an 11-year, $3 million undertaking piloted by Frischer and made possible by scholars of antiquity from around the world. His simulated ancient city includes 7,000 unique buildings and the undulating terrain they rest upon. When finding one’s way within the virtual space, dubbed RomeReborn 1.0, the user wearing 3-D specs easily identifies hills and valleys with a realistic sense of depth. The software engine that brings this sim city to second life is called MultiGen Creator, and its forte is mapping landscapes—during the Cold War, the software was classified because Air Force pilots used it to virtually bomb Moscow, according to Frischer.

Now, in a more peaceful incarnation, the software is poised to act as an online resource to scholars of assorted disciplines who consider themselves experts of ancient Rome. The tool is designed more for researchers than it is for in-class use. "Think of [RomeReborn 1.0] as a new kind of peer-reviewed journal," says Frischer. Out of the 7,000 buildings within the city, detailed archeological accounts exist for 250 of them; Frischer and his colleagues have thus far digitally restored 31 structures to the minutest detail. Opening the model up to academics near and far will allow that figure to grow. No new skin will adorn an artificial edifice without rigorous erudite debate.

The completed version of Rome-Reborn 1.0 will be online and navigable soon for scholarly subscribers, thanks to a $400,000 grant from the National Science Foundation.

C-VILLE welcomes news tips from readers. Send them to news@c-ville.com.