Remixing, riffing, playing with memes: These are artistic modes that we sometimes think of as belonging to our own time, as though it was only in the 20th century, and only in Western countries, that artists began to knowingly recycle material. Think Roy Lichtenstein, Beastie Boys, and anybody who’s used the image of RBG’s lace collars. But artmaking has involved self-conscious imitation for a lot longer, and in a lot more places—including several hundred years ago in Asia, as revealed in “Earthly Exemplars,” a small exhibition of Buddhist art now showing at The Fralin Museum of Art at UVA.

“The exhibition features materials mainly from the 17th through 19th centuries,” says curator Clara Ma. “That was a time when there was lots of cultural exchange and diplomatic exchange between Qing China and Tibet, and also there are connections between China and Edo Japan through trade.” In choosing pieces to highlight—from elaborate paintings called thangkas to sculpture to an astonishing painting on the leaf of a Bodhi tree—Ma hopes to demonstrate that China, Tibet, and Japan were involved in a complex swirl of cross-influences.

Walking into the show at The Fralin, that concept probably wouldn’t hit you immediately. Instead, you might be struck by the delicacy and precision of, say, a painting from Tibet, made in the 17th or 18th century, showing the Goddess of the Victorious White Parasol. She has a long name (Ushnisha Sitatapatra), a thousand faces, and a thousand arms, which are actually depicted in a dizzying, overlapping arrangement like a sunburst or a bullseye. Her ferocious power—maybe even greater than a Supreme Court justice—contrasts with the serenity of the deities around her, and the loveliness of flowers and leaves.

Or you might be drawn to a thangka, also Tibetan, showing the life story of Pindola Bharadvaja, an arhat—a disciple of the Buddha, that is, venerated in his own right. In this piece, he sits on a throne in the center of the painting, surrounded by vignettes from his biography. The piece is lush and rich, even with a constrained palette of red, green, blue, and white; it conjures a whole world and a lifetime. And Ma says its landscape, and the ornate Chinese-style throne on which the arhat sits, are elements a Tibetan artist would have borrowed from the art of the Qing dynasty. “There would be missionaries or diplomats the Qing sent to Tibet with gifts of paintings, or vice versa,” she explains. “So the style or the composition, they got influenced through these exchanges.”

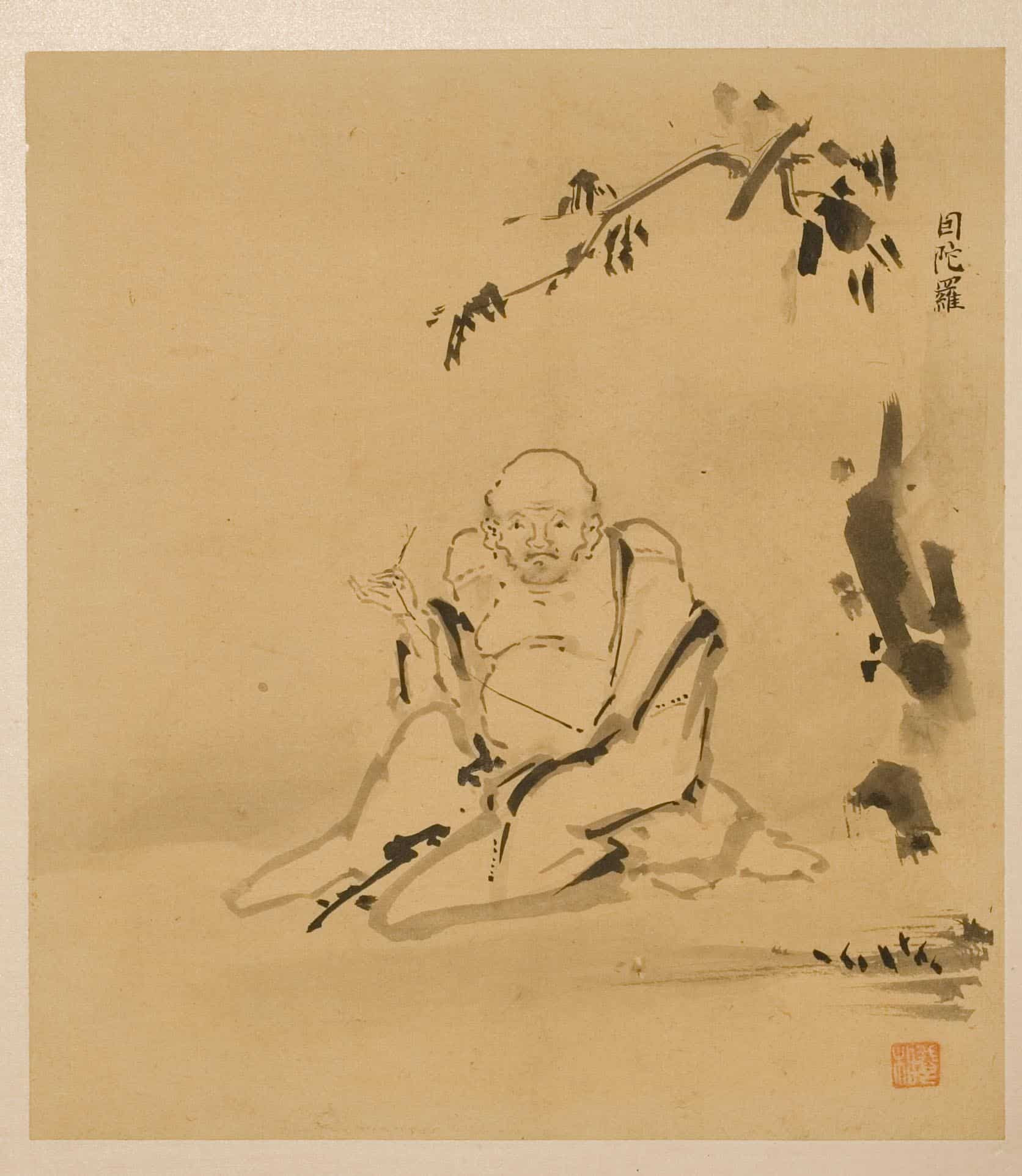

She says we can think of these connections like souvenirs—bringing home a new idea for how an image could look or a technology for making something, like the woodblock print that closes the show. But maybe an even better analogy is fashion. To get dressed is to refer to any number of cultures and histories, making oneself a living library of clothes. A Japanese album from around 1695, made by a court painter named Kanō Tsunenobu, amounts to an artistic wardrobe: Tsunenobu used the album to demonstrate his mastery of different painting styles, including the loose, poetic look of the paintings Ma highlights.

“The way he created it was to study Chinese painting at the court,” she says. “At the time, China was the center of Zen, and lots of Japanese monks went to China. They’d bring back a lot of the Chinese paintings. He’s making the claim, setting up that lineage for his own art school: ‘We have these deep connections, our school has this long history.’”

It sounds very modern, like a 21st-century piano student learning Bach one day and Scott Joplin the next. “I guess one way to see that is that these artists, for them to establish their own identity is not to come up with something totally new, it’s to connect themselves to different traditions.”

There’s even another layer of borrowing going on here, she points out—one that she wasn’t able to represent in this show. “They are all making connections to India,” she says, “but I didn’t select any Indian artworks. It’s all about these regions trying to connect back to India.”