| More features:

Local CSA farms Trouble in paradise |

Eat well, do good. How can you go wrong?

Local food, it’s no secret, is big around here. Farmers’ markets thrive. So does a lively restaurant scene and a string of grocery stores that cater to a simple hunger: nutritious, safe food grown in ways that don’t poison the environment. And more and more people are going one step further toward the source, buying into a peculiar farming model, community supported agriculture (CSA).

There’s a reason they call it seed money. If you want to live the good life, people, now’s the time to pony up.

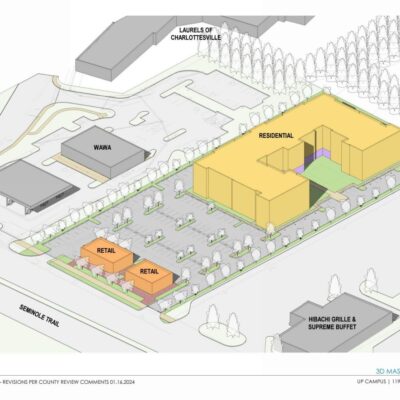

Annamaria Little and Michalis Manias work the soil at Innisfree Community Gardens, which began in 1971 and currently contains 15 households. |

So what is a CSA? The concept dates from the ’60s, of course (the decade will haunt us forever), and according to some accounts made its way to the United States from Europe and Asia in the mid-’80s as a way for farmers to secure their market early in the season and consumers to buy good fresh food. Around Charlottesville, the millennium is seeing CSAs sprout quickly.

People buy shares in the spring, when farmers need money, and in return get weekly boxes of fresh produce through summer and into fall: vegetables, often flowers, herbs, sometimes eggs. Some farms offer various meat arrangements, but those are separate from the weekly box routine that’s the hallmark of a CSA. Locally, the basic deal is a weekly box of seasonal produce for 20-22 weeks, beginning in mid-May. Prices range from $328 for a single share to $675 for a family of four. The average share price for a two-person family is $467. All the CSAs on our list have weekly deliveries to Charlottesville, a couple to Crozet. You can pick up at the farm if you’d like, and there’s usually a discount if you’re the one who expends the fuel.

The original concept was that shareholders would add their labor to the farmer’s—i.e., they’d help out on the farm a few times per month or per season—and accept the risk of a poor harvest—i.e., they’d have to eat the several hundred bucks they’d ponied up, rather than the heirloom tomatoes they’d hoped for. But in practice, American consumers have found a way around that pesky risk thing, and not everyone wants to get his or her hands dirty.

Here’s how it is in 2008: Some, but not all, CSAs offer workshares, where you can work at the farm once a week, in return for a lower share price. Arrangements vary, some requiring interviews. More commonly, CSAs ask for three or four voluntary work days during the season when members can come out to help with seasonal chores like harvesting garlic.

The labor at Innisfree is provided by five to 15 residents who are regularly involved in starting seeds, and cleaning and packing produce, among other duties. Pictured here is Katie Brubaker. |

It’s not only the work that’s a challenge for members, but the reality of truly seasonal cooking. “CSAs aren’t for everybody,” says Trisha Costello, head gardener of Innisfree. “You have to enjoy the surprise.” Shareholders range from those who embraced the challenge of weekly fresh vegetables—“it forces your hand and presses you to eat organic,” says shareholder Betsy Greenleaf—to those who felt inundated under a wave of okra or unpronounceable greens.

One shareholder who tried working for a season was put off by how hard stoop labor (harvesting chamomile flowers) turned out to be and has found the bump-into-people fellowship at farmers’ markets more to her liking. Another found the upfront share fee to be too steep for her single-member household. Peter Warren, local agent for the Virginia Cooperative Extension, will share a CSA share this season with a friend. “What I like best,” Warren says by e-mail, “is the variety of fresh, organic vegetables/fruit, the challenge of making something out of it all. Since you do not choose what you get, it makes you try new things, eating seasonally—this both supports local agriculture and it gives an understanding of what grows when in Central Virginia.” Among the few downsides, he continues, is “once in a while receiving too much of one thing, such as squash.”

Appalachia Star Farm owners Michael and Kathryn Bertoni, at work here with their son Eli, grow 40 different varieties of vegetables. |

We’ve collected vital stats for seven regional CSAs and visited four of them, traveling in all directions: north towards White Hall to hilly Innisfree where dedicated people have lived their ideals for a generation; south to the river plain of Scottsville and the ambition of a rock star’s good intentions to provide The Best of What’s Around; west through ragged jagged Nelson County to the alp-like hamlet of Roseland and tiny Appalachia Star with its young family hitched to it; and finally east to where the foothills spill into the piedmont around Louisa and Ploughshare’s Tony Lagana creates biodynamic concoctions to heal the earth, and schemes to bring people together for their own good.

Innisfree: tending plants and people

From Rte. 810 in White Hall, a narrow gravel road winds toward Innisfree Village through buff fields backed by naked blue hills and all of a sudden you seem very far from everywhere. A large mobile pen of free range chickens sits in a pasture near one of the greenhouses, and a flock of raucous guinea hens patrols the dusty farm road. Everything is simple and bare, raised beds within a fenced acre still shaggy with cover crops and mulch.

Late in her ninth month of pregnancy, cheerily swaddled in woolen sweaters, coat and cap, Trisha Costello and her husband, Cabell Coward, meet me early one nippy morning in March outside the low-slung potting shed. We enter through a door patted all over with colorful handprints. “Ours is a very hands-on operation”, Trisha says. “We have a lot of hands.”

As Cabell begins watering trays of seedlings in the adjacent greenhouse, Trisha sits at a bench and talks about her time at Innisfree. The village contains 15 households, and dates from 1971 when it was established by a group of parents of children with mental and physical disabilities. She has tended plants and people here for 20 years and speaks fondly and authoritatively about the operation.

The gardens began as a way to grow food for residents and staff. After branching out to local farmers’ markets for a few years, four years ago Trisha and her colleagues started the CSA and began selling shares to the public. “A big foundation of CSAs is connecting people with their source of food but also with each other,” she says, and for Innisfree this applies even more for their residents and staff—co-workers all—than it does for their public shareholders.

Innisfree is one CSA that doesn’t require labor from its members, who have topped off at 35, with a waiting list. Instead, the labor is provided in part by five to 15 residents who are regularly involved in production. Starting seeds, transplanting, harvesting, weighing, cleaning and packing produce add new dimensions to their life skills and social interactions, supporting Innisfree’s mission to provide meaningful, productive work. They won’t expand indefinitely. “There’s such a demand for CSAs, we could get bigger but we have to balance that with what’s best for our therapeutic environment,” Trisha says.

A couple of shareholders do work regularly in return for a longer season rather than a reduced share price. Other members can jump in via seasonal events, including the popular and festive potato dig in late summer, followed by a dip in a swimming pool that looks out towards a seascape of rippling blue ridges.

Trisha believes that CSA farmers have a responsibility to provide a variety of produce. She tries to provide staples like squash, beans and over 20 varieties of tomatoes, while occasionally introducing something new—like sweet potato greens, which were such a hit last summer they’ve joined the basics.

“Farming is the easy part. Building community is the hard part,” says Ploughshare owner Tony Lagana. |

Trisha describes the farm’s horticultural practices as “bio-intensive with organic principles.” “We nurture one piece of small land,” she says, and producing so many vegetables in such a restricted space requires careful soil management. They don’t spray chemical pesticides or use chemical fertilizers, relying instead on compost and kelp. “We work with the cosmos and moon phases.”

Following up during the week, I find that Trisha and Cabell had a fine baby girl a few days later. You gotta give it to them, these are productive people.

The Best of What’s Around: star power and a hard place

Born from musical magnate Dave Matthews’ effort to save parts of the old John Kluge estate from development, Best began in 2003-2004 as an organic farm. Not every CSA has a bona fide rock star behind it, but Best has had its ups and downs under a series of different managers. It’s the largest CSA in the area, with as many as 200 shares at one time; its website lists 40 acres in production with over 50 different crops. There was a bit of a dust-up last season when members were offered refunds because of a hitch in production, and a large percentage—farm manager Matthew Holt won’t say exactly how much—left the CSA.

That baptism of fire was the first full season for Holt and his wife, Suzanne. A trim, well-dressed couple, they meet with me one afternoon in a spruced-up garage neatly renovated as a modern office, walking down from the large white farmhouse where they live nearby.

Alone among local CSAs, Best has been organically certified from the start. Suzanne keeps tabs on organic seed sources, amendments applied per acre, pest control, tracking yields, and the rest, part of demanding record-keeping necessary for federal certification. But the Holts go way beyond organic.

They have the cool collected manner of efficient managers, but the story they tell is one of adventure and faith in unseen forces. They “rattled around for a while” after college, investigating dairy farming at one point and ended up in Pittsboro, North Carolina, where they had their epiphany.

They “ran into a bunch of old tobacco farmers” who, though steeped in chemical agriculture themselves, enjoyed sharing the folk wisdom of their grandfathers with eager neophytes. “We made huge mistakes and bad assumptions but we listened to the old people and learned to farm the old ways before chemicals,” says Matthew. And Suzanne adds, “We were like their grandparents after awhile,” planting with moon phases and astrological signs and canning and preserving.

The Holts ended up owning five acres and leasing another 20 where they built a successful CSA, until the owner developed it out from under them. Losing their customer base with the acreage, the Holts had to sell out, but they came away with a complete trust in natural systems, from the timing of seed sowing and planting according to moon phases and astrological signs, to dealing with insects and diseases.

They recount a plague-like infestation of aphids in North Carolina where they forced themselves to watch their tomatoes wither for a week until successive waves of ladybugs and chickadees picked the plants clean. The plants rebounded, free from any natural or synthetic pesticide. Last summer at Best, an unchecked Japanese beetle invasion affected but a negligible block of basil, as the insects consumed only what they needed to continue copulating among the asparagus fronds in a natural cycle that wreaked no devastation. There was a little damage done, but in the end there was enough for everyone.

I say “Amen.”

Matthew and Suzanne speak affectionately of those who stayed on during the lean times (only four of 25 workshare members opted out last summer), mostly older folks with “a good work ethic” and shared memories of gardening as children.

The Holts are focused now on creating a healthy, self-sustaining system for the human element, not just the crops. Workshare participants get a hefty discount in return for committing to a minimum of two and a half hours a week as regular members of the crew. “When you have people who just ‘volunteer’ it can be disruptive. It had gotten to the point where people were just coming when they wanted and no community was being formed,” says Matthew.

Appalachia Star: family life, and a living

Kathryn and Michael Bertoni’s place is the idealized image many might have of a typical CSA. Their farm encompasses just under five acres, with over half of that in production. It sits in a steep valley in Nelson County’s Roseland, over Brent’s Mountain, 20-30 minutes west of Nellysford.

A little creek runs through it and the simple ranch house sits just above the cultivated bottomland, dominated by an ancient maple, with children’s toys and a picnic table in the front yard. Two hoop houses filled with seedlings nestle against the driveway. As I steer down the precipitous gravel drive toward the little farm spread out before me like a Grandma Moses painting, I expect to see a bluebird on my shoulder.

They’re both bent over rows of greens, a coffee cup perched on the fence post. Kathryn’s mom is up from Richmond for the day taking the two toddlers to the library in Lovingston for storytelling. After the bustling off, they both sit down at a picnic table to tell me a story of their own.

They bought the land five years ago and have steadily built an organization of 50 shareholders. They established Appalachia Star (named for the mountain chain as well as their aim to be a “star” in the CSA firmament, according to Kathryn) after interning at Waterpenny Farm in Rappahanock County, a noted incubator for hopeful CSA farmers.

“We got married, bought the land and planted garlic on our honeymoon,” says Kathryn. They use no chemical fertilizers or pesticides and strive for a healthy bio-diversity, using compost, hay mulch and trace minerals.

They like the rhythm of filling weekly distribution boxes for their CSA. It fits well with the farmers’ markets, and allows a more even distribution schedule. They make a go of it between the two. You never know how sales at the market will go, but with the CSA, you know what and how much to pick. The markets take a lot of time and preparation, packing up and packing down, where the work of the CSA is all on site, except for deliveries once a week to Charlottesville and the Rockfish Community Center.

They grow 40 different varieties of vegetables, so there’s always something. Last year, they “pretty much lost the whole sweet potato crop,” says Kathryn, “but were able to make it up with other items.”

They don’t have a formal workshare program, though they tried one the first year. Now, like most of the other CSAs, they offer volunteer days where members can help with things like winter squash harvesting, the weeding of the garlic and the demanding but thrilling tomato-tastings. “We enjoy having that connection with our members, just knowing that we have 50 people,” says Kathryn. “A lot of them have become friends.”

Michael affirms how useful the cash flow is from members early in the season, but still, he says, “things get a little tight now and then.” They manage to break even, though. “It’s a modest situation,” he says.

Kathryn chimes in sweetly, “I can’t think of any downsides for us.” As I leave through the back door, they are drinking a cup of something hot in the kitchen and she asks him, “Do you want to get back to the greens?”

I drive back eastward toward Albemarle County and a pair of blue herons swirls like pterodactyls high above for a good quarter of a mile, following the creek that parallels Rte. 151. There‘s no one in front or behind so I slow my car to a good crawl as I watch them glide down the waterway and disappear through the trees, and it’s like I’m leaving paradise.

Ploughshare Community Farm: growing a system

Everyone I talked to in the CSA world told me about Tony Lagana. They’d get an affectionate grin on their faces, sparkle a little and say, “Oh, you’ll love Tony.” Ploughshare is situated in the most open land I encountered on this trek, a broad saucer of fields and pasture with the mountains a distant smudge on the horizon instead of right up in your face.

Ploughshare is wherever Tony is. It used to be in Richmond ‘til a series of apocalyptic weather events, Hurricane Isabel and the Shockoe Bottom flooding, followed by the loss of the land they were leasing to development, forced them out in 2004. “It was a sad day when we left Richmond.”

So now Tony and his wife, Rebecca, three children, and Ploughshare are in Louisa, farming on eight leased acres enclosed by a black plastic deer fence, living in an early 20th century Sears kit farmhouse, crumbling a bit at the edges. Large maples, an old beech and errant daffodils marked the defunct entrance, as I drive around to a more utilitarian gravel parking area along the side of the yard.

A jovial, friendly fellow dressed in work clothes, with an outstretched hand, Tony comes down to greet me and leads us back to a small round kitchen table in a tall old farmhouse room, sparsely furnished. He proceeds to tell me all about Rudolph Steiner’s philosophy of biodynamics and potions involving various organic matters interred in different bovine body parts, which produce micronutrients that work with humus to unlock trace minerals that make food healthier. You may delve further on his website.

He is proud of his “flagship,” 200 tons of biodynamic compost, created solely from organic material harvested within the farm. “I did it to save myself,” he says. He’s talking about biodynamics as a perfect holistic system of sustainability, a way to heal the land, with each farm becoming a unique organism following its own rhythms, but he could just as well be referring to Ploughshare. “As a biodynamic farmer, our first goal is to provide sustainability. It’s a calling.” For Tony, a CSA is “not a product [shareholders] are purchasing, but the action of supporting a community farm.”

Back in Richmond, his shareholders worked 12 hours a season and he needed a coordinator to keep everything straight. “Our shareholders ran the CSA. But around here, people would rather pay than work.”

They had a hard time last year, couldn’t make their sharebase and lost money, but he’s committed to involving people not just with their food but with the social issues of the day. He asks all his shareholders to donate part of their produce to food banks and holds monthly potlucks and “issue forums.” His goal is to set aside 40 percent of his sharebase for low-income people. “Farming is the easy part. Building community is the hard part.”

He used to require some labor from all his shareholders, but now he offers “unspoken workshares” where he interviews an interested applicant to see if he or she is willing and able to work four to five hours a week through the season. Successful applicants pay no fee. Most shareholders pay the full fee and participate in various work days, like the upcoming potato planting followed by a dinner and potato sack races. He has an open book policy and shareholders are welcome to inspect the finances.

He’s telling me all about CRAFT as he walks me out, the Collaborative Regional Apprentice Farmer Training program where he and many of his fellow CSA operators give tours and presentations on small farm management and different production techniques. These leased acres and what he produces on them are his life.

He chats a bit more at my open car door as we say goodbye and rain begins to spit. I turn back toward Charlottesville and think musing highway thoughts as I pull out of the farm. The real community in CSAs is not the shareholders. I suspect they’re a fickle bunch.

It’s these small farmers who are betting it all, vanguards of post-industrial agriculture, working hard to find ways to make the land productive without ruining it. They’re looking risk straight in the eye.