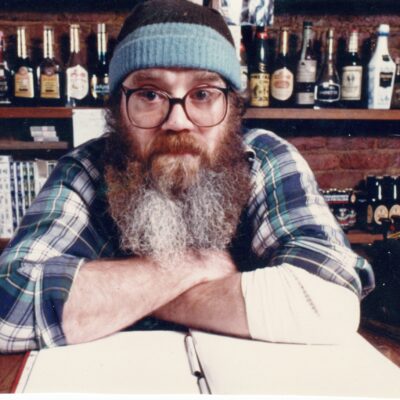

The new browser-based game Initial Instinct hinges on a simple and elegant premise: Assign famous names to two random letters and rack up points under a time limit. Though the game is perfectly suited to an internet-connected smartphone, the idea for Initial Instinct actually dates back to designer David Levinson Wilk’s high school days. The creator of C-VILLE Weekly’s reader-favorite crossword puzzles (see page 33) says he and his friends would play a pencil-and-paper version of the game “constantly.”

“It became an obsession,” he says. “I’m fairly certain there were kids who cut class when there was a game going on in the hallway that they wanted to join.”

Today, Wilk is head writer on ABC’s “The $100,000 Pyramid” and “The Chase,” and he’s carried the game with him through his career, getting co-workers in the television world hooked on it, too. It wasn’t until a year ago that he discovered the potential to convert this childhood game to a digital experience through the website peoplebyinitials.com. The searchable database of “notable people via initials” takes any monogram and quickly draws up lists of names with corresponding Wikipedia pages. It seemed like the perfect system to power Wilk’s game, so he reached out to the programmer who built the website—the mononymic Enzo.

“I originally created this website to generate 100 initials for the Dominic number memory system,” says Enzo, in reference to a memory training system inspired by author and “memory champion” Dominic O’Brien. “David contacted me from that site and asked if I would be interested in developing a game with him based on the database of people.”

With Enzo on board as programmer, Wilk needed someone to handle the graphics. For that, he turned to his peers in television. Paul Stack, who builds games and graphics for “Watch What Happens Live with Andy Cohen” on Bravo, had been introduced to Wilk’s name game during his own time at “The $100,000 Pyramid.”

“David laid out the bones of how he wanted the game to play,” says Stack. “He had this idea to have dials, similar to ones on a briefcase, at the center of the letter choice. Taking that idea, I started working on visual layouts and timing.”

Wilk loved Stack’s minimalist designs. “When he first sent me a mockup of the spinning dials, it was thrilling,” says Wilk. “He made the site look clean, inviting, and supremely user-friendly.”

But what looked great as a visual design turned out to be a challenge on the programming side. Enzo says the most difficult thing to accomplish for Initial Instinct was taking the 3D spinning wheel animation video files and converting them to web code like HTML and JavaScript. The animation videos were smooth and included lighting effects that just didn’t translate well to the web without additional coding.

“We ended up using the Adobe [After Effects] videos, one video for each letter and left-right combination,” says Enzo. “Mobile devices, especially the iPhone try to delay playing or loading video in the background to save battery, so playing the animations exactly on time with the game timing was tricky.”

Of course, getting the 1.4 million names to pop up in the correct format—with the right occupation for each famous person—was its own challenge.

Wilk, Enzo, and Stack developed Initial Instinct over email, beginning with a prototype and building on consecutive versions.

“I quite like the iterative approach to development,” says Enzo. “I think this works well for a game where you can have many iterations of playing and improving.”

Ultimately, the team decided that Initial Instinct would work best as a web-based application rather than a downloadable mobile app. This enables phones and desktops to play the same game. Which means you won’t be getting the game off the App Store anytime soon.

“I have no desires, as yet, to develop an app,” says Wilk. “To me, getting people to enjoy Initial Instinct is really all about accessibility and, as it exists currently, anyone can play it at any time. … I think it’d make a very good game for a room of people for trivia night.”

For now, Wilk is busy on the picket lines, thanks to the Writers Guild of America strike, which began in May and escalated when SAG-AFTRA went on strike in July.

“While it’s no fun and not a single writer wants to be on strike,” says Wilk, “we have to do this now or the majority of us—and an even greater majority of future writers—won’t be able to have sustainable careers in TV and film.”