What we have with Appaloosa is a faithful adaptation of Robert B. Parker’s 2005 novel, directed by Ed Harris and co-scripted by him and Robert Knott. It’s Harris’ second film as director and certainly a departure from his first, 2000’s Pollock.

Harris and Viggo Mortensen play two transient 1882 lawmen, Virgil Cole and Everett Hitch, who take it upon themselves to remove the gangster-rancher Randall Bragg, played by Jeremy Irons, from the eponymous New Mexico town. It’s clear from the outset that Virgil and Everett are the right men for this job, or as right as is possible, and so they’ll need to be: The last guy who tried to bring Bragg down didn’t come back.

“I knew Jack Bell,” Virgil says of his unfortunate predecessor. “He was a good man.” Come to think of it, that might be the very first thing Virgil says in this movie—a perfect or perfunctory opening line, depending how you like your Westerns.

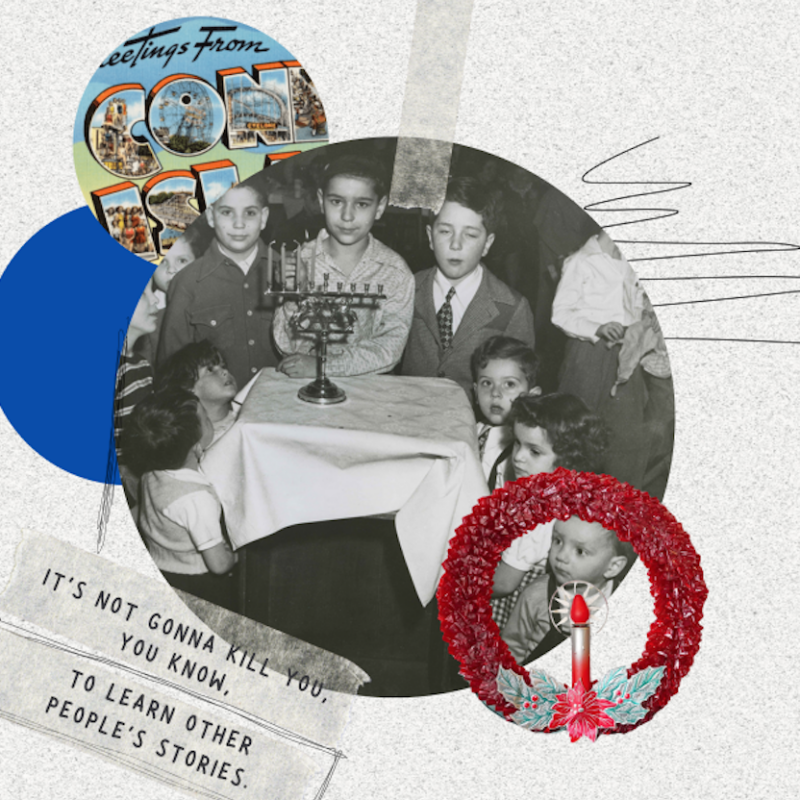

|

The Western shall rise again? Viggo Mortensen and Ed Harris hope so, as they set their guns to “Blaze” in Appaloosa. |

Virgil’s the sort of man who warns gunmen that if they draw on him, he’ll kill them, then does, then says, “I warned ’em.” Everett’s the sort of man who always has Virgil’s back. He’s always ready, for example, with the word Virgil is looking for, or the eight-gauge shotgun blast. Their brand of taciturn male camaraderie is not uncommon in movies of this genre, from Shane to Rio Bravo to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and it is the essential substance of Appaloosa.

Another example: When a comely widow, played by Renee Zellweger, steps off an arriving train, Everett takes note, then Virgil takes note, then Everett takes note of Virgil taking note. Then the job they’ve come to town to do suddenly gets more complicated. And so on.

Back to the matter of how you like your Westerns. It’s a fair point to accuse Harris of merely going through the motions here: The escalating plot basically involves one tense standoff after another; the pace is unhurried; the framing and cutting are standard; the score sounds more like something for TV rather than for a movie. It is easy, in other words, to go into Appaloosa expecting ironic, detached deconstruction and feeling vaguely disappointed to find the film so unvarnished and conventional.

But it’s just as easy, after settling in and getting seduced, to then begin wondering why exactly you figure the Western should always have to be reinvented. Appaloosa wears both its traditional values and its modern touches lightly, and there’s no shame in that; this is archetypal, enduring stuff. Harris and Mortensen on horseback, staring folks down with their steely eyes, or gunning them down in the dusty streets, seems like part of what movies were invented for.

More than that, Irons’ sneering villainy and Harris and Mortensen’s charming chemistry make a convincing case, still relatively rare among movie adaptations, that this particular tale need not have remained content to only be a book.