Correction appended

When you step into the box office at The Paramount Theater, it hits you—everything in this place is for sale. To buy tickets, one must stand in the BB&T vestibule, at ticket windows sponsored by LexisNexis, Hantzmon, Wiebel & Co. and a couple named “Taylor.” The auditorium itself, a renovated movie theater which has drawn big concert audiences for the past couple of years, was sponsored by Hunter J. Smith, wife of late UVA alumnus and philanthropic superstar, Carl W. Smith.

Anyone who’s ever gone to an instrumental concert has likely picked up on the rich vibe. A sea of tailored jackets, gobs of fur, sparkles and plenty of grey hair lends the impression that wherever there are violins, there’s bound to be a lot of money in the room.

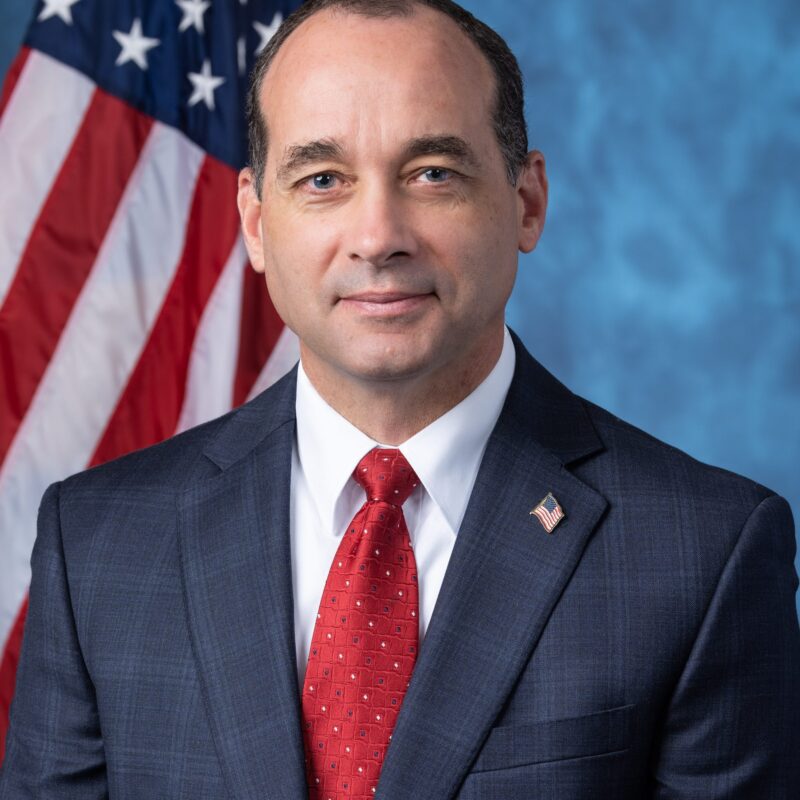

Karen Pellón balances renowned talent and money at the Tuesday Evening Concert Series: “It’s a source of pride for me to always operate in the black.” |

Maybe. But, talking to arts managers around town, one learns there’s a reason why every column and seat cushion gets its own sponsor. It’s because, from a business perspective, there’s no money in classical music.

I meet first with Jane Colony Mills, director of development at the Paramount. The Downtown theater is known for many genres, including its cheesy nostalgia acts, but also books internationally famous classical artists.

“The general opinion in Charlottesville is that we’re rolling in it,” Mills says. The Paramount is currently undertaking a $3 million capital campaign to endow its operating costs and programs.

But, the theater’s administration also carries $3 million in capital debt for the large theater. Excepting a grant they’ve applied for from the Virginia Commission for the Arts, the Paramount sustains itself on ticket sales, program advertising and donations.

It costs a lot to see a show at the Paramount. Tickets for renowned violinist Itzhak Perlman last year ranged from $50 to $500 (there was a fundraising component). Yet the theater only takes in 57 percent of its revenue in ticket sales. (Even this sum is more than other arts organizations, which typically make only one-third to one-half of their revenue selling seats.)

To keep prices reasonable, the Paramount caps the fees it will pay an artist at $75,000. With approximately 1,000 seats, that can push ticket prices to an average of $75—that’s before concert staffing and other expenses.

With ticket sales a tricky formula, a big part of keeping an arts organization stable is good ol’ fashioned fundraising. Annual memberships at the Paramount range from “Associate” at $75 to the “Leadership Level” at $25,000. Mills must be doing a good job—perusing the Paramount donors list is enough to make the average music fan feel downright shabby.

Charlottesville may seem to have plenty of folks with both culture and cash, but smaller classical music organizations, often featuring local performers, must compete for the same audience that attends the Paramount’s big-ticket dance, opera and instrumental offerings.

Bill Martin, director of Charlottesville and University Symphony Orchestra (CUSO), acknowledges the scene is active, but says, “I don’t think it’s reached the saturation point.”

From the orchestra’s modest offices on Elliewood Avenue, Martin tells me the symphony doesn’t directly compete with the Paramount’s classical offerings. Though it may seem a mathematical impossibility, Martin says, “The success of one [organization] helps the others.”

CUSO has the benefit of University support—they rent out UVA-owned Old Cabell Hall, and student performers make up the bulk of the talent, with paid principals anchoring the ensemble.

The symphony currently has an endowment of $1.2 million and just launched a $3 million capital campaign, which should help it in its goal to balance beautiful concerts with the shockingly expensive cost of putting them on.

In contrast is the Virginia Consort, a community chamber chorus that performs three or four big concerts with orchestra each year at a cost of $25,000 to $30,000 each.

The Consort doesn’t really have an office—I meet with conductor Judy Gary and concert manager Ina Arnold at Arnold’s home on Brandywine Drive. In fact, the Consort’s shoestring staff numbers just six people, including Gary, Arnold, a music librarian and part-time accompanists.

When the Paramount opened, Gary and Arnold worried about waning audiences and measuring up to the lights and fancy upholstery.

“People who bring in all these outside names are wonderful, but they don’t support the local scene,” Gary says. “We’re not just competing with other groups…we’re also competing with entertainment in general. …How much can you do in a weekend, even if you have the money?”

To solicit donors, the Consort sends out a simple letter each year, and currently has about 150 donors. The Consort also has a development board to up fundraising efforts.

But, Gary admits, it can be hard to make that phone call to ask for cash. “We’re musicians,” she says, “Not fundraisers.”

To sustain themselves, most arts organizations find they must be both artists and fundraisers. When Karen Pellón took over the venerable Tuesday Evening Concert Series (TECS) in 1991, she found herself in charge of an organization that was in debt, with spotty programming and lackluster audiences.

Pellón, a former dancer, has an M.B.A. in arts administration. She is well aware that with a few financial missteps, any local organization, including the Paramount, could fall into debt.

“These organizations have to be run as businesses,” Pellón says. “It’s a source of pride for me to always operate in the black.”

The Tuesday Evening Concert Series has been able to “remain purist” about the music; the series brings internationally renowned chamber artists, along with little-known but serious talent from around the world to Old Cabell Hall, regarded as the best-sounding place in town.

Underwriters include the likes of Charlottesville wealth management firm Silvercrest, and TIAA-CREF.

Certainly, the Tuesday Evening Concert Series, like many other local organizations, entertains its share of “blue bloods.”

But, Pellón says, it’s not stuffy, and it’s not all about the money.

“People who come on a Tuesday night, it’s not a social thing. It’s not to be seen,” she says. “It’s to be comfortable and love the music.”

Correction May 29, 2007:

Due to a reporting error in “Where the money isn’t,” May 22, 2007, we incorrectly stated that The Paramount Theater’s auditorium was sponsored by Hunter J. Smith. It is the Paramount’s ballroom that is named after Hunter J. Smith. The auditorium itself is not named.