By Karen L. Mulder

What do Clinton’s secretary of health, the founder of Netflix, a prominent African American sculptor, and one host of “This Old House” have in common? Each served in the Peace Corps: Donna Shalala in Iran, Reed Hastings in Swaziland, Martin Puryear in Sierra Leone, Bob Vila in Panama—and don’t forget Jimmy Carter’s mother, Miss Lillian, who nursed lepers in India at age 68.

The Peace Corps is still the heartiest expression of Kennedy’s challenge to do “what you can do for your country,” and one of the most effective delivery programs for American goodwill overseas. Not everything conceived in the 1960s still works that well, but if you’re wondering whether current global affairs derailed this vision, look no farther than Charlottesville.

Last year, the Charlottesville area had the most Peace Corps volunteers per capita in the nation. And among universities, UVA came in second place this year, with 74 Hoos in the field—missing a tie with top-ranked University of Wisconsin-Madison by just one. You can bet that Peace Corps campus recruiter April Muñiz (Senegal 2010-2012) and regional recruiter Matthew Merritt (Lesotho 2013-2015) will redouble their efforts in 2019. Merritt and others chalk up Charlottesville’s Corps spirit to a community of retired, civic-minded citizens, a large refugee population, and a university that’s increasingly become globally oriented.

Since 1961, a cumulative tally of about 230,000 PCVs nationwide, aged 18 to 87, has served in 141 countries. Each year, a corps of 3,000 begin their service with an intensive, three-month training in language, health care, and acculturation. They acclimatize in their host country, which has invited volunteers for specific, localized projects, starting a 27-month tenure under experienced instructors. Up to a fourth of each cohort drops out.

UVA sent 74 new recruits to the Peace Corps this year, missing a tie with top-ranked University of Wisconsin-Madison by just one. Hoos are currently serving in more than two dozen countries across the globe. Courtesy Peace Corps.

Last month, new initiates and returnees tossed back the hops at Champion brewery during a welcome home/send-off blast, and screened Girl Rising, a documentary about girls seeking education in adverse situations—a scenario that PCVs often witness firsthand.

Cliff Maxwell (Nepal 1979-1981), for instance, taught only 16 girls in a school of 435 students. Anna Sullivan (Bolivia 2005-2007) befriended an illiterate mom of six who explained that as soon as she could write her name, in second grade, her family yanked her out of school to work. Muñiz observed how Senegalese boys reached high school, but girls got pulled into the workforce by their early teens.

Now recruiting from Newcomb Hall, Muñiz was almost 40 when she left for Senegal after a 20-year career in pharmaceuticals, inspired in part by her godparents’ positive Peace Corps experiences in Kenya during the 1970s.

Muñiz’s primary collaborator in the small city of Diourbel was a Senegalese native named Phayé, who ran a nonprofit dedicated to environmental education. Born in Dakar, Phayé remembered Diourbel as a lush, forested setting, verdant with peanut plantations and groves of fruit. When French colonizers left in 1960, many regulations also departed, and people began chopping vegetation down indiscriminately, allowing the Sahara to creep in.

“I’d listen to him and friends talk about how it used to be,” Muñiz remembers. Phayé’s life mission, and Muñiz’s main task, became educating the community’s youth, and changing attitudes. As Muñiz observed, “Outsiders come in wanting do good, but if they don’t pass along accountability, it won’t be a sustainable solution.”

Even well-intentioned international aid often misses the mark. “For instance, I looked into beekeeping and discovered a European nonprofit that bought some impressive equipment for a Senegalese community. By the time I got there, the honey hut was a junk shed, and people were back to robbing hives without maintaining them. Or, one campaign provided free mosquito netting to counteract insect-borne diseases. We’d always see those nets covering lettuce gardens.” Sustainable, practical initiatives owned by the host community are key to Peace Corps’ success.

UVA alum Henry Maillet took this photo of a boy in an UVA cap he met during his service in Paraguay. “It definitely reminded me of how small the world really is!” he said.

Rising to the challenge

To be effective, says nurse Michael Swanberg (Burkina Faso 1999-2001) “you have to work with people’s strengths and abilities, see what’s needed, and strategize in ways you never would have imagined.”

In his 40s, Swanberg became his family’s third PCV, interrupting his career to volunteer in the second-most illiterate country in the world, where teachers were being decimated by AIDS. He noticed young girls were the ones sent to the watering hole, where he and others were teaching about waterborne diseases.

“Every day, I brought chalk, and I’d teach a different letter of the alphabet,” he recalls. “And one day, one girl learned enough letters to write her name for the first time, and I thought, ‘Wow!’”

Another turning point for Swanberg, less exalted, happened when robbers broke into his house. “They took everything—including the window they came in through!” he recalls. “For the first time, I really felt like part of the community. We were all there with nothing, together. My vulnerability was plainly visible.”

After his service, Swanberg pursued education, earning a masters degree from Columbia (thanks to a Peace Corps scholarship), and teaching in Harlem. Eventually, he completed a Ph.D. at UVA on social disparities in maternal and infant health care, collaborating with a team that included two other former PCVs.

For Georgetown Law grad Chris Register (El Salvador 2001-2003), the challenge was helping Salvadorians earn a better living. Register helped organize a women’s jewelry-making cooperative, laying out a salary structure based on hourly contributions. He purchased materials and Dremel drills with an $800 Peace Corps grant—one of several project-based PC grants available, as long as host communities put up 33 percent of the requested amount.

“I was a little concerned about the men getting upset with me when their wives started making more money!” he recalls. “But they knew me,” and, against all cultural norms, even ended up babysitting during the day. “It’s completely on you as a volunteer to make things happen,” Register says. “If you want to start something, you need to figure out how to do it. The opportunities are there, but Peace Corps doesn’t exactly sit you down and tell you how.”

Last year, Register returned to see the co-op going strong, even though Peace Corps suspended its service to El Salvador in 2016. He attempted to set the business up on the internet, but says that connections are still too unreliable.

Former volunteer Chris Register on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. After his return from El Salvador, Register biked across the United States, interviewing Americans for a book project. Photo courtesy subject.

Regional recruiter Merritt, on the other hand, had better 3G service in Lesotho than he does now, in his living room near Richmond. As an undergrad, Merritt didn’t even know that Lesotho was an African country. He never took a single public health class before he found himself teaching about trafficking, HIV, and healthy sexual behavior.

At first, he basically only knew “hello” in Sesotho, and thought perhaps his red hair was causing commotion until he realized that villagers thought he was Prince Harry, who sponsors an orphanage in Lesotho. But like other volunteers, Merritt eventually found his way, helping his village raise chickens so they could earn money to buy HIV meds for a third of the community’s children, infected with AIDS.

“My phenomenal host mother became my language teacher, mentor, best friend, and if things got hard…my watchdog,” he says. “No one crossed Manthati.” She encouraged four daughters towards higher degrees in education, international relations, and evaluative theory, and cultivated beans, potatoes, and sorghum. When she suddenly died last year, Merritt says, “it was like losing a family member.” He flew back to Lesotho for the funeral and gave a eulogy in Sesotho, “crying through the whole thing.”

Making it work

Charlottesville-born Anna Sullivan grew up hearing about her parents’ Peace Corps adventures, cheerily joking from her office at UVA’s Career Center that she has failed to leave Charlottesville on multiple occasions. But in 2005, she and husband Tom moved from Belmont to Okinawa Uno, a colony of Bolivians descended from Japanese farmers who were invited to enhance agricultural yields after World War II. Bolivian Okinawans still cultivate most of the nation’s soybean harvest, and have accrued conspicuous wealth that segregates them from indigenous Bolivians, raising tensions. She befriended families that basically live Japanese lives, “right down to the karaoke bar,” Sullivan says.

Wielding only her UVA masters degree in educational psychology, Sullivan ended up constructing composting toilets, drilling wells, networking with a nun in a pickup truck who collected plastic waste from isolated settings, and coaching women to take leadership roles alongside the men in city government. When a newly elected regime of sanitation managers asked her team about building a new sewer system or a 30,000-gallon water tower, she realized their perception of what the Peace Corps did was seriously out of whack.

Working communally on a much smaller scale, she partnered with a cooperative that wanted a water testing lab, but lacked capital. “So, I wrote a grant to the Bolivian government, and we met with them…and it worked! We staffed that lab with locals we trained.” Governmental strife intervened, and one day in 2007 a Land Cruiser roared up to Sullivan’s remote work site: she had 10 minutes to join a military C-14 full of PCVs and return to the States. Hundreds of Peace Corps programs remain suspended in Bolivia.

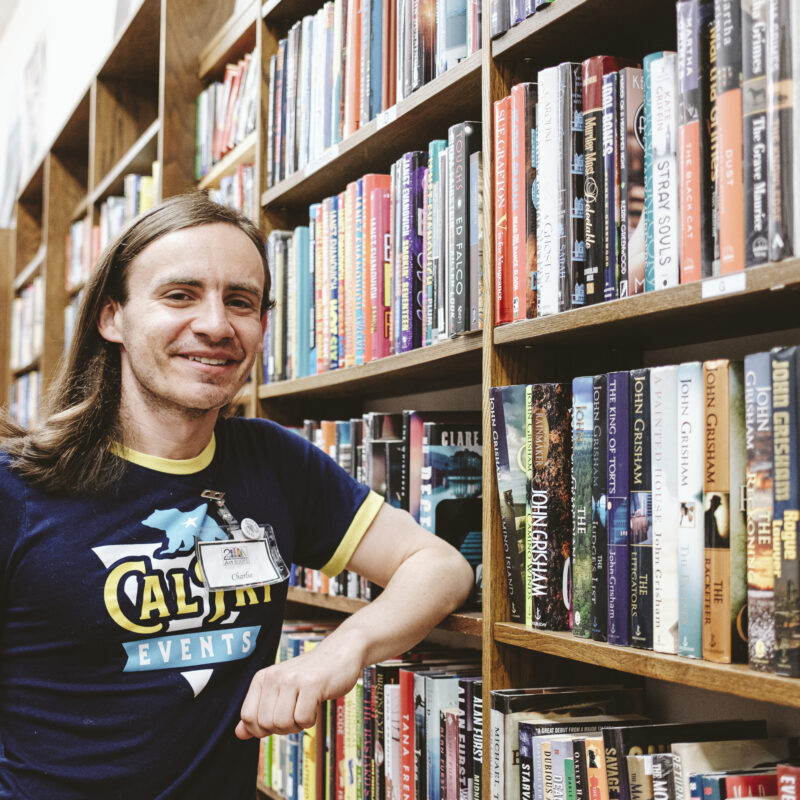

Henry Maillet (above, left) fell in love with Paraguay and its people during his just-completed Peace Corps tour. Though he’s now back in Charlottesville, Maillet has already planned a return trip to document the effects of climate change on riverside communities.

The longest uninterrupted Peace Corps presence has been in Paraguay. Skyping from a cement hut, UVA graduate Henry Maillet admitted that he had “totally fallen” for Paraguay’s people, topography, waterways, and regard for nature. Maillet relies more on photography than language skills to socialize, mindful of the selfie’s power as an instant conversation starter. “It’s such a cool way to synthesize the experience of the moment,” he says. Working on a water supply project with a youth group, Mallet was astounded to spot a boy wearing a UVA cap. “I still don’t know how he got it…but it definitely reminded me how small the world really is!”

Now back home in Charlottesville, Maillet has already made plans to return to the country: In a few months, he and another PCV will embark on a rowing trek down the length of the Paraguay River. Working with the World Wildlife Federation, they plan to photograph and interview people from 179 riverside communities, to document the effects of climate change on their way of life.

Donning his Batten School of Leadership mortarboard for a moment, Maillet described Paraguay’s unique class structure, sorted by language rather than ethnicity or race. “Spanish is key for economic advancement,” he says, “but Guarani is the first language—it provides the social and cultural glue, it’s the storytelling language.”

A word like aranduka’a’ty simultaneously alludes to ancestral folklore and deep plant wisdom. “This is what your grandma teaches you, passed down for generations,” he says. “Every time I’ve gotten sick, my host family made some herbal concoction. When my dog got sick, my host mother made a necklace out of corn on a string, and said, ‘When the corn falls off the string, the dog will be healed.’ I was kind of like, ‘wha—? That’s crazy.’ But I learned that it’s just a fun way of saying, ‘time heals.’ She didn’t believe the corn had magical powers. She was just teaching me a fundamental truth.”

For Cliff Maxwell, tasked with teaching math and sciences in a remote village in Nepal in 1979, the question was how the Nepalese king’s insistence on British curriculum would possibly benefit his students: Why explain Ohms law of electricity to a land without electricity? Instead, Maxwell related science to local features, like water wheels, and encouraged independent thinking, demonstrating the benefits of problem-solving rather than having “right” answers.

“As teachers,” he worried, “we weren’t making tangible things like bridges or improving the water, so we never really knew if we’d succeeded or failed.” Returning in 2011, he was deeply touched to see former students running schools and health organizations; one even earned a doctorate. “But I got the sense that they were saying, ‘We don’t know that your teaching ever did anything, but staying here and living with us like you did—that was love. That was the biggest thing!’”

Maxwell cherished the simplicity and grace of Nepalese life at that time, with “no army, no crime, no police force, no overt theft or murder.” The customary PC stipend matches the local pay scale, and he says, “They had nothing—so they really knew the meaning of generosity—and I had nothing, so I was truly with them.”

Peace Corps returnees and new recruits gathered at Champion brewery for a welcome home/send-off party. Photo: Martyn Kyle

Bringing it all back home

Re-entry is rarely easy. Touching down at Dulles, Merritt says, “I was like, oh my god, a Starbucks, let me get a real coffee…and then I heard someone complaining to the barista about too much skim milk. I am so appreciative about everything now. I complain very little—except when I complain about people who complain about everything!”

As Maxwell recalls, “Wherever I walked in Nepal, I always had a place to stay. It shocked me, landing in Los Angeles and just knowing that there was nobody along the way that I could ask for a bed, or a garden hose for a shower. I felt utterly alone.”

The “plasticness” of American society galled him: “Nepal completely changed the way I thought about my home culture. Here, you can buy an apple any day you want, but it never tastes like much—there, even wormy and half rotting, they tasted real.” After studying cultural anthropology, Maxwell left for Sri Lanka on a Fulbright Scholarship, researching his UVA dissertation on Theravada Buddhism. He eventually landed at UVA Global, and teaches development theory from a Buddhist perspective.

Like many volunteers, Chris Register says he got much more back from the Peace Corps than he gave, and calls it the best decision of his life. Since his return, he’s left law to focus on connecting to people, biking through the entire U.S. and interviewing “real” Americans in every state about issues that matter to them. He’s turned the project into a book series, which he recently launched at Peloton Station.

“The best overseas money the U.S. government spends” is the $410 million allotted annually to the Peace Corps, he says. “What I know is, there are at least 150 people in El Salvador who know not all Americans are big jerks. They got to know a real person.”

Raised in Venezuela, Karen Mulder is an art and architecture commentator and a writer/editor who has called Charlottesville home since 2000.

On the home front

Many Peace Corps alums continue their humanitarian work after they’re back in the U.S., and in Charlottesville, returned volunteers have brought their energy and problem-solving skills to a range of local initiatives, from public policy to education. Here’s just a sampling of projects powered by former volunteers:

International Neighbors

Kari Miller (Thailand), founder

Miller started International Neighbors in 2015 to help Charlottesville’s growing number of refugee families find community connections and support.

EcoVillage Charlottesville

Dave Redding (Korea), co-founder

EcoVillage is an innovative residential development, off Rio Road, that seeks to foster community and sustainable living.

International Rescue Committee

Harriet Kuhr (Zaire/Congo), executive

director, and Elizabeth Moore (Cameroon), New Roots coordinator

The Charlottesville office of IRC helps refugees and asylum seekers settling in our area to rebuild their lives. Their New Roots program operates an urban farm, community garden, and neighborhood farm stand.

Center for Nonprofit Excellence

Christine Nardi (Botswana),

executive director

CNE helps nonprofits increase their impact through training, consultation, and connection with community resources.

Network2Work and

Great Expectations, PVCC

Sarah Groom (Grenada), peer

network coordinator

Network2Work connects community job-seekers with employment opportunities and training, while the Great Expectations program helps students who were or are in foster care meet their career and education goals.