By Merrill Hart

Formal fraternity recruitment at the University of Virginia concluded on Saturday, January 25. There are 28 chapters in good standing at UVA, but that didn’t stop some Hoos from rushing groups operating outside the Interfraternity Council system.

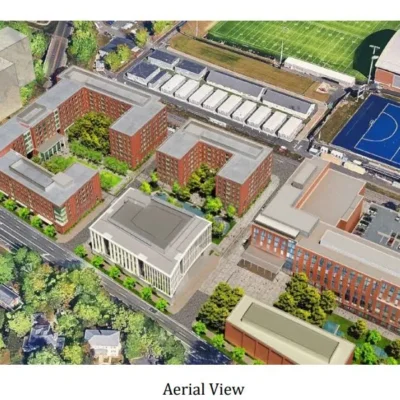

The red-bricked estates lining Rugby Road’s Mad Bowl briefly went silent last spring when the IFC called a three-week suspension during a hazing investigation that drew national controversy. Over the past year, UVA administration has terminated its relationship with three fraternities found guilty of various hazing activities, and sanctioned two others.

Hazing is a crime in Virginia. And since the 2022 passage of Adam’s Law following the death of Adam Oakes, a freshman at Virginia Commonwealth University, the state requires schools to offer anti-hazing training to student groups. At UVA, all potential new members must complete mandatory Hoos Against Hazing training before rush.

UVA has terminated the fraternal charter of five organizations since the passage of Adam’s Law: Kappa Sigma, Theta Chi, Pi Kappa Alpha, Kappa Alpha, and Phi Gamma Delta (also known as FIJI).

Similar concerns weigh heavily on campuses across the country, including nearby University of Maryland, where leaders placed a cease and desist order on 37 fraternities and sororities last March. In response to a lack of consistent data, former president Joe Biden signed the first federal anti-hazing bill in December 2024, requiring all colleges and universities to disclose hazing incidents in their annual security reports.

While hazing culture faces heightened scrutiny, interest in Greek life at UVA remains strong. The IFC reported a 10 percent increase in prospective fraternity members this January compared to last year. Around 800 potential new members participated in this winter’s rush process, which culminated in Saturday’s bid day.

Some potential new members say they are navigating the social scene with an eye for safety. First-year student Godwin Mensah, who is pledging Phi Delta Theta, said the reputations of certain houses significantly influenced his decision on where to rush.

“Hazing, sexual assault, and homophobic culture are all very serious things to me, and I definitely made sure to avoid chapters that have had a history of that in the past,” Mensah said over text. “I made it a point to rush chapters that I knew I’d feel safe and accepted in because being Black, [first-generation low-income], and bisexual, I don’t think I represent the typical frat guy, but that shouldn’t bar me or anyone from Greek life, and we all deserve safe spaces.”

Mensah said he appreciated UVA’s efforts in investigating hazing reports and transparency about which chapters have been suspended. The school’s hazing misconduct page includes a summary of each case—confirming, for example, that a new member of Kappa Sigma was hospitalized last year with life-threatening injuries. The Pi Kappa Alpha report details an incident where a new member was duct-taped to a wooden cross and had hot sauce poured on his genitals.

For others, joining a fraternity represents a cornerstone of the college experience—one where connections with brothers outweigh other uncertainties.

“I’m rushing a fraternity that was previously kicked off campus due to hazing, but I haven’t let that history define my impression of them,” said first-year student Aidan Floyd, who is actually pledging Club 128, which operates out of the now-terminated Phi Gamma Delta house. “The members I’ve met have been incredibly kind and welcoming, which has mattered far more to me. Ultimately, I’m just looking for a place where I feel a genuine connection and can see myself thriving within the brotherhood.”

The UVA Student Affairs office notes the risks of joining “any terminated organization that may continue to operate,” including Club 128.

When asked whether the university will monitor potential underground rush activities of these organizations, spokesperson Bethanie Glover said the administration no longer has a relationship with terminated fraternities.

“Groups that continue to operate while terminated jeopardize their ability to re-establish at the University at a future date,” Glover said in a written statement. “The University cautions students and parents regarding the safety risks of potential involvement in these organizations given their terminated status and safety concerns associated with past behavior.”

Fraternity life’s enduring popularity comes alongside ongoing efforts to combat hazing. Over the last year, the IFC has worked with the Office of Fraternity & Sorority Life and The Gordie Center, a foundation dedicated to the prevention of hazing and substance abuse. Ben Ueltschey, former IFC president and a fourth-year UVA student, said over email that the IFC facilitated conversations about root causes of hazing and now requires each chapter to submit new member education plans.

To help those rushing make informed decisions, the IFC has introduced new measures, including rush counselors who guide underclassmen. This year’s cycle also features a second open house round designed to maximize the number of students who successfully receive bids, Ueltschey said.

The road to end hazing, however, has included some stumbling blocks. Donovan Golich, a student affairs associate director tasked with handling investigations, left UVA in November 2024 amidst criticism of his policies. In an interview with The Cavalier Daily, he said the university still had significant progress to make in fostering an effective anti-hazing culture among students—especially given fears of social repercussions for speaking out.

It remains to be seen whether evolving policies and sanctions will put an end to hazing practices this year. As the newest pledges take steps toward becoming brothers, the balance between tradition and reform will continue shaping the narrative of Greek life at UVA.