How did that happen?

Every time you sign the check for your water bill, you’re paying the price for years of misadventures in water supply planning. Our water rates include money for two water expansion plans that have since been flushed, even though the debts remain.

Now the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority is under pressure to do something…anything…to get more water to this rapidly growing region. But are they headed in the right direction?

Water pressure

“We want to get something done,” Michael Gaffney, chairman of the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority’s Board of Directors declared at a recent RWSA meeting.

An entrepreneur accustomed to making things happen at his company, Gaffney Homes, the chairman seems frustrated at times with the glacial progress of the RWSA.

Over the past 30 years the RWSA has tried, unsuccessfully, to expand the local water supply, which currently provides Charlottesville and Albemarle about 13 million gallons of water per day (that figure does not include the Beaver Creek Reservoir that supplies Crozet up to 2 million gallons per day). The RWSA says we will need an extra 9.9 mgd by 2055. At last, the Authority is honing in on a solution—maybe.

The RWSA has identified four options for expanding the local water supply: 1) raise the dam of the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir; 2) dredge the sediment out of the South Fork, thereby getting more out of existing capacity; 3) raise the dam of

the Ragged Mountain Reservoir; or 4) build a pipeline to the James River from Charlottesville.

Few dispute that the Charlottesville area, with a population of about 125,000 and growing by about 1,500 people annually, needs more water to satisfy residential and business demand. But as the options for increasing supply come into focus, the matter of where our water comes from is becoming an ever more pitched battle.

Pipe dreams

Although Fluvanna and Louisa counties already have met with the RWSA to discuss sharing the cost of a pipeline as a means to get enough water to feed the soon-to-be sprawling Zion Crossroads area, the James River pipeline is a very unpopular option. Water from the James River is more polluted than our current reservoirs—Rick Parrish at the Southern Environmental Law Center says we don’t know exactly what contaminants might be in the James, but he notes that we’re just downstream from Lynchburg. The pipeline could also trigger a burst of real estate development in Fluvanna and Louisa, and the pipeline would run through rural southern Albemarle, where groundwater supplies currently limit development potential.

On March 1, a group of 17 people from a range of city and county groups—the Piedmont Environmental Council, the League of Women Voters, Citizens for Albemarle and others—sent a letter to Charlottesville Mayor David Brown and Albemarle County Board of Supervisors Chair Dennis Rooker outlining their concerns with the James River pipeline and the water planning process in general.

“There is no immediate ‘water crisis,’” the letter asserts. “With the addition of the water from Beaver Creek… this community would feel no shortfall of water supply even during the most severe drought through the year 2018.”

The letter goes on to warn officials against simply installing a pipeline in the James and leaving the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir to clog with sediment. Further, the letter says that some of the cost estimates are misleading. The nearly $50 million price tag that’s cited for the James River pipeline, for example, does not include potential expenses for improved water treatment systems that water from the James might require.

“A lot of people in the community are reluctant to embrace a pipeline,” says Charlottesville Mayor David Brown. “They want to expand our existing supply, but we’ve received some advice that there might be too many regulatory hurdles.

“The question is,” Brown says, “can we proceed in a direction that seems economical and that has community support?”

So what’s the answer? The fact is that after months of planning and public meetings, elected officials are only now trying to exert influence on the process. Whatever the solution turns out to be, it will be directed by a handful of people.

Conspiracy theories

The tussle over the James River pipeline is the latest episode in a water supply planning saga that over three decades has been marked by political turmoil.

The RWSA has been trying to expand our water supply since the late 1970s, to no avail. Back then, the Authority paid $6 million for land along Buck Mountain Creek in Free Union in the hope of adding a third reservoir to the local water supply. Unfortunately, plans for the new reservoir fell through in the mid-1990s, when regulators discovered the endangered James Spinymussel and shut down the project. But though the Buck Mountain reservoir died, the cost did not: New water customers still pay a $200 surcharge when they start service to cover the cost of the land.

By 2002 the RWSA had devised a new, far less ambitious plan. This one called for raising the height of the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir with a 4′ inflatable bladder, and for rehabilitating an abandoned pump station on the Mechums River. That plan was projected to cost $13.2 million. The City and County spent months hashing out a way to share the cost, and both the Charlottesville City Council and the Albemarle County Board of Supervisors instituted water rate increases to pay for the 2002 plan.

Two years, ago, however, the RWSA scrapped the 2002 plan and started over. RWSA officials claim that the data supporting the 2002 plan was skewed by miscalculations, not to mention the severe drought that hit Central Virginia. The plan, they said, was faulty.

Rich Collins, former RWSA chairman (and current candidate for the Democratic nomination in the race for the 57th District Assembly seat) helped create the 2002 plan and he just doesn’t buy it.

“It’s a lame excuse,” says Collins of the allegedly skewed data. “To me, the reversal is still unexplained.”

Whatever happened to the 2002 plan, it’s clear that the RWSA has undergone significant changes since then. The most obvious shift came in 2003, when Gaffney, an active member of the Blue Ridge Homebuilders Association, replaced environmental activist Collins as chairman of the RWSA board.

Collins founded UVA’s Center for Environmental Negotiation, and helped organize Advocates for a Sustainable Albemarle Population (ASAP). That group contends that growth via real estate development is not the economic Holy Grail some developers might have people believe. ASAP is often seen as the nemesis of the Homebuilders Association, which generally opposes public restrictions on private landowners.

When Collins ran the RWSA board, local developers claimed a conspiracy was afoot. They floated rumors that the Authority was intentionally bungling water supply plans as a covert scheme to stifle growth. The Daily Progress took this nonsense seriously and ran the developers’ whining in a series of editorials in October 2002.

Now it’s the environmentalists’ turn to cry foul over concerns that real estate interests are pushing the RWSA towards the James River pipeline.

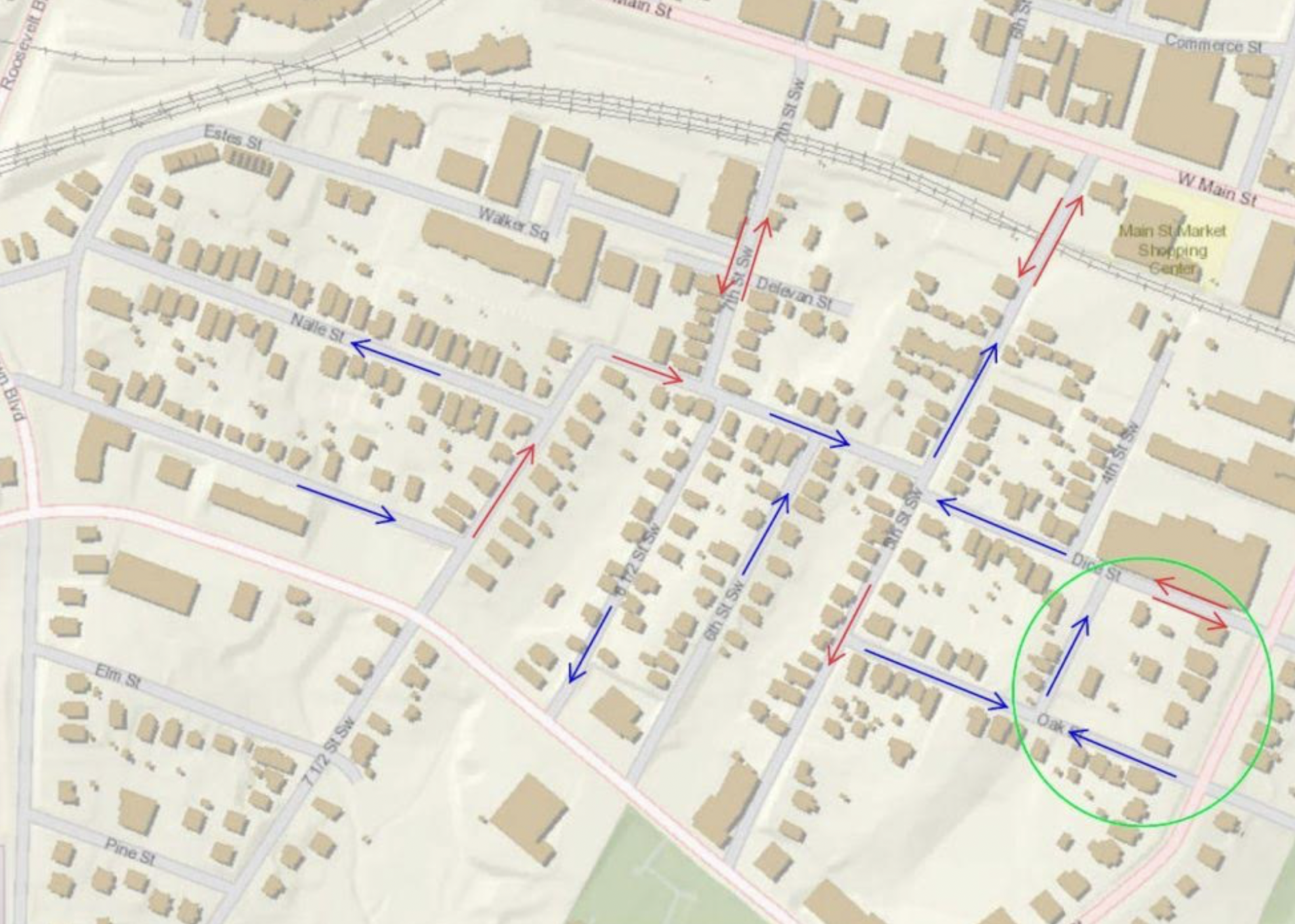

Since 2003, the RWSA has spent $1.1 million on a team of consultants led by Gannett Fleming, a Pennsylvania-based engineering firm with nearly 2,000 employees that specializes in huge projects, such as dams, bridges and industrial buildings. Gannet Fleming and their subcontractors, VHB, have performed a litany of studies on water needs and held several community meetings. In the process, they’ve whittled 20-some options down to the four now under consideration [see chart].

Collins says that the James River pipeline had always been discounted in the past, because it was too expensive. That seems to have changed since 2003. “It appears that now the business community and the RWSA feels that the only option that will work is the James River pipeline,” says Collins.

While developers don’t explicitly state their preference for the James River pipeline, they do hint at it.

Environmental Protection Agency guidelines say planners must choose the “least environmentally damaging, most practicable” water supply option. In determining what constitutes the least environmentally damaging option, the EPA looks almost exclusively at the amount of wetlands a particular option will disrupt. Since the pipeline only disturbs an estimated .23 acres of wetlands, it is, when seen through a very narrow lens, the least damaging option. Thus, when the pro-growth Free Enterprise Forum insists that the RWSA choose “the least environmentally damaging” option, it sounds like a reference to the pipeline. It would, after all, provide a virtually unlimited supply of water to areas whose development potential is currently limited by groundwater supplies.

Gaffney’s close ties to the development community (he’s also on the board of a start-up bank that seeks a foothold in the region), and the renewed interest in the James River pipeline that’s become apparent under his chairmanship, have prompted some claims that local developers have “hijacked” the RWSA, as City Councilor Kevin Lynch suggests.

While Collins and Gaffney may disagree on the costs and benefits of new subdivisions, they agree that conspiracy theories—in either direction—don’t hold water.

“I don’t think [Gaffney] has hijacked anything,” says Collins. “I think he’s doing a good job.” Previously, Gaffney has seemed to discount the conspiracy angle. He was unavailable for an interview with C-VILLE Weekly by press time.

Indeed, it seems hard to imagine that the Authority, which hasn’t even been able to complete a new water project despite three decades of effort, would be able to pull off a secret plot of any kind.

That’s not to say that there hasn’t been a shift in the RWSA. The 2002 water plan is full of phrases like “the RWSA staff believes we have a responsibility to protect and enhance the environment as an integral part of our water supply mission” and “RWSA needs to be more active in watershed protection.” Talk about the RWSA’s environmental responsibility has all but disappeared under Gaffney’s leadership, regardless of political pressure to consider it.

Hands on the tap

Another recent episode involving the RWSA’s attorney, a Richmond lawyer named Bill Ellis, is also fueling speculation that the Authority is trying to push the James River pipeline.

On Friday, March 4, The Daily Progress ran a front-page article covering the previous day’s meeting among the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority (RWSA), City Council and the Albemarle Board of Supervisors.

The article, headlined “Expert opposes 2 water options,” described Bill Ellis as a “consultant” and quoted him as saying, in reference to water supply choices, “I feel very confident the four-foot crest and dredging won’t be approved.”

With that statement, Ellis was effectively nixing any improvements to the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir, and moved the RWSA one step closer to the James River option. The Councilors and Supervisors in attendance at the meeting expressed dismay over Ellis’ statement, given what they cite as broad political support for improving the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir and virulent opposition to drinking from the James.

Some people have started to wonder on whose behalf Ellis is arguing, and whether he’s giving all the facts.

Morgan Butler and Rick Parrish, two attorneys for the Southern Environmental Law Center, attended the March 3 RWSA meeting. After hearing Ellis’ comments, Butler sent a letter to Gaffney and RWSA Executive Director Thomas Frederick.

“We both believe it would be premature to remove the South Fork Reservoir options from consideration,” Butler wrote.

Ellis claimed to be speaking on behalf of the environmental regulators, but when the SELC attorneys called Jim Brogdon of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Joe Hassell of the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, the regulators told them something different: Despite Ellis’ claim, they had not ruled out the South Fork Rivanna options.

“These gentlemen made clear that…none of the options currently under consideration can be ruled out at this point,” wrote Butler and Parrish. Ellis declined to comment to C-VILLE on his statements at the meeting or on the SELC’s letter.

Regulators, mount up

After reading the SELC’s letter about Ellis, City Councilors and County Supervisors decided they wanted to hear firsthand what the regulators had to say.

On April 18 the elected officials met with a flock of State and federal regulators—from the Virginia departments of Game and Inland Fisheries, Health, Conservation and Recreation, Historic Resources, Environmental Quality, as well as feds from the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. All these agencies, of course, have a say in how the RWSA proceeds with its water plan.

Maybe they were reluctant to insert themselves into a local political argument, but the regulators didn’t say much.

“It was a wishy-washy meeting,” says Ed Imhoff, an Albemarle resident and former California water planner who sits on the State Water Planning Advisory Committee.

Imhoff noted that the assembled regulators didn’t rule out any specific plan. Despite what we’ve heard locally, it seemed that as far as the State and federal regulators were concerned, everything was still on the table—a bladder on the South Fork, dredging there, even a new reservoir at Buck Mountain Creek.

“We’re not running out of water,” says Imhoff. “We have time to look at other options. I think [the RWSA] is frustrated by having spent a good deal of time and money, but I think the worst thing that can happen is for us to rush ahead.”

About the only helpful information that emerged from the April 18 meeting is that the EPA and other regulators encouraged the RWSA to hold a preliminary meeting in which regulators can review a plan and advise the RWSA on whether it will be approved.

So the new question becomes, which plan will the RWSA submit for review? That decision falls to a few people—Mayor Brown, Supervisor Rooker, Gaffney, Ellis, a Gannett Fleming consultant and Randy Parker, a local lawyer and board chairman for the Albemarle County Service Authority.

“We’re meeting right now,” says Parker. “We’re trying to come up with a consensus plan to pitch to the regulators. At this point, there is no consensus.”

Brown and Rooker, the politicians, have both indicated they want to focus on

the South Fork Rivanna. Ellis has said he doesn’t think a plan that involves the South Fork Rivanna will get approved. Parker declined to say which option he’s rooting for. “I don’t think it’s appropriate to say until we come up with a consensus,” says Parker. “Maybe there won’t be one.”

The sudden uproar over the James River pipeline points to an obvious flaw in the local water-supply planning process. Asked about theories that the RWSA is trying to either limit or promote growth, Authority officials insist that it is the responsibility of local political officials, not the RWSA, to make land-use decisions. It’s the Authority’s job, they say, to provide the water for those decisions.

If that’s the way it’s supposed to work, then why did we get two years into the latest water supply plan before elected officials stepped in to say they would prefer if the RWSA stayed inside the Rivanna watershed?

Recalling his water-planning career in California, Imhoff describes how Los Angeles simply stuck pipes in rivers to fulfill a dream of prosperity through endless growth, only to wake up and find their rivers dry and their land devoured by sprawl. There is a clear, if unspoken, battle about the costs and benefits of real estate development swimming just below the surface of the water debate.

“I think there’s a substantial body of people in the middle [of the growth debate] who think that elected officials should weigh in more,” Parrish says, “that you don’t just turn it all over to a utility.”