My day to talk with Dr. Russ Federman about mental health at UVA comes just two days after the Virginia Tech shooting.

An expert on campus mental health and UVA’s director of counseling and psychological services (CAPS), Federman has become a popular guy. That morning, he gave an interview on NPR’s “All Things Considered” about dealing with mentally ill students on campus. Media outlets everywhere are curious about the state of mental health at schools in Virginia and around the nation. Early the following week, he would testify before a United States Senate committee about safety on campus.

Dr. Russ Federman |

As we chat, Federman munches on a handful of almonds—it could be the first thing he’s eaten all day amid the chaos following the Tech shooting.

It’s difficult to ask him the questions I had planned, since I suspect we’ve both got the same tragic incident at the front of our minds. Seung-Hui Cho, a Virginia Tech university student, massacred 32 people before ending his own life on April 16. His glossy forehead, blank stare and dead eyes made even more frightening by hindsight have been plastered all over newspapers, TV news and the Internet.

As relatives told The New York Times, Cho’s issues began in childhood in Seoul, South Korea. Cho was painfully shy. He wouldn’t play with other children, wouldn’t speak to his parents or relatives.

By the time the family moved to the United States in 1992, Cho was an uncommonly reserved 8-year-old. Some reports have even suggested Cho had autism. His great aunt, who stayed in Seoul, hoped the U.S.’s open culture would help bring Cho out of his shell.

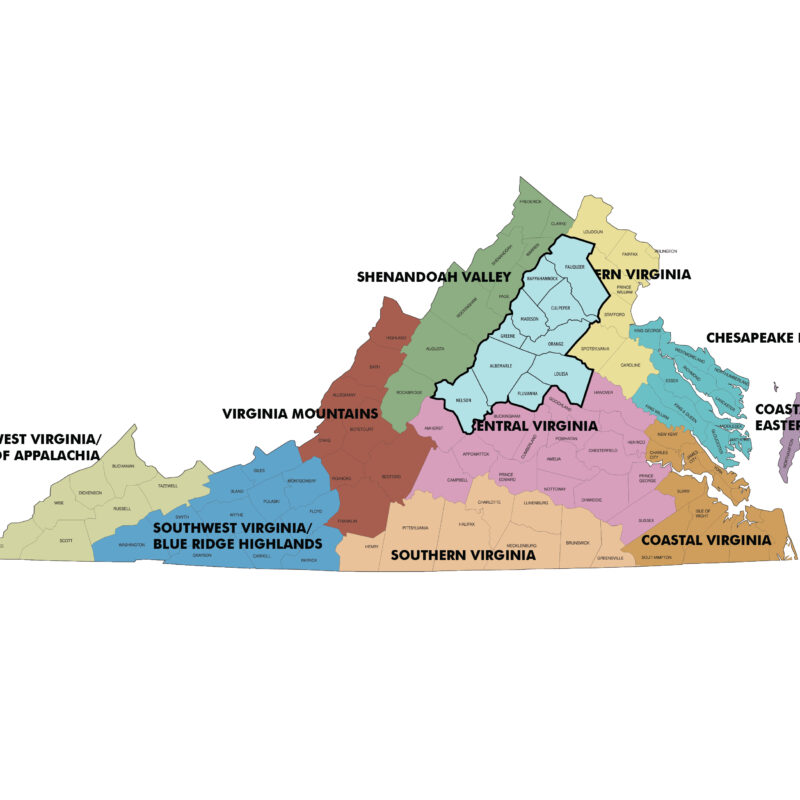

But at Westfield High School in Fairfax, Cho was teased for his silence and, when he spoke, his accented English and strange, deep voice. He retreated to videogames and would shoot baskets alone outside his family’s modest row house in Centreville, ignoring greetings from neighbors.

His parents were desperate to get Cho to open up. But he hadn’t been diagnosed with any psychological disorders, per se. When the time came in 2001 for the parents to drop off their son, without fanfare, on the campus of Virginia Polytechnic Institute in Blacksburg, Cho became the university’s problem.

A period psychologists term “late adolescence” and the unsupervised environment of college seemed to compound Cho’s issues. He had a made-up girlfriend named “Jelly.” He told a roommate he vacationed with Vladimir Putin.

Cho was removed from a creative writing class his junior year for writing disturbing poems and nightmarish plays that frightened other students. He would ignore fellow students’ attempts to connect, that blank stare perpetually adorning his face.

Cho was referred to counseling in 2005 after two female students reported him for stalking them. They didn’t press charges, but Cho was deemed an “imminent danger” to himself or others by a magistrate judge in December 2005. He was briefly hospitalized before being released for outpatient counseling. Cho never sought the help the judge said he needed.

When the long-disturbed Cho finally snapped, it happened slowly and methodically early this year. He purchased one gun, a .22-caliber Walther pistol, in February from a website and picked it up at a Blacksburg pawn shop. A little over a month later, he purchased a Glock 9mm from gun dealer Roanoke Firearms. He also purchased cargo pants, a hunting knife, and ammunition, and made videotapes in several locations—investigators estimate Cho spent thousands of dollars, charged to a credit card, prepping for April 16’s slaughter.

He rose early that morning, his suitemate said, around 5am. It would be hard not to know the rest. By 9:45am, Cho had massacred 27 students and five instructors and wounded dozens of others in campus buildings. He worked methodically, survivors have reported, shooting no victim fewer than three times, yet taking his time to reload his weapons. He also found time to go to the post office to mail a package—a “multimedia manifesto” of his rage—to NBC’s New York City headquarters.

All the while, Cho stayed silent, his trademark blank stare covering his face. When state troopers began to close in, Cho shot himself.

Culturally, the Virginia Tech massacre may stand out as many things: fuel for the fire of gun control debates, a platform for political posturing, possibly even a model for copycat killers. But for campus administrators like Federman, already tasked with keeping tender-aged populations of students healthy and safe, Cho is an example of the nightmare that could lurk beneath the surface of campus life.

“A tight-knit safety net”

I had been communicating with Federman for a few weeks before the Virginia Tech incident about the difficult work of providing mental health services to the college set.

As Federman would tell the Senate committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs in an April 23 hearing, “The college years represent a complex period of development… This is a transitional time where core values and mores, emotional states, day-to-day functioning and the broad spectrum of interpersonal relationships undergo considerable change.”

Of the nation’s 17-18 million college students, one in 11 has sought counseling in the past year. According to national data, 94 out of 100 college students report feeling overwhelmed by academics and activities.

Students who seek counseling at UVA are no different.

| UVA psych services by the numbers

Number of patients seen : 1,733Percentage of patients who are female: 60 Percentage who are white: 66 Percentage who are upperclassmen: 48 Percentage who are depressed: 32 Percentage with adjustment disorders: 16 Source: UVA Counseling and Psychological Services Annual Data Report, 2005-06. |

Federman describes a scenario common to elite university settings. An overachieving student, perhaps a valedictorian or musical genius, accustomed to being at the top of the heap, finds herself lost in the crowd of other top-notch students at UVA and, subsequently, has a personal crisis. Though UVA students are more likely to seek counseling in their third or fourth year, the initial personality crisis of arriving at college can be dramatic.

Annual data reports from UVA’s CAPS show a third of treated students are depressive, about 20 percent have anxiety, and around 15 percent have an adjustment disorder, which Federman describes as “trouble adjusting to…a clearly identifiable precipitant,” like a breakup with a significant other or fighting with parents.

To deal with these issues, CAPS uses “brief therapy, within the six to 10 session range” before students are referred to local psychologists in private practice.

Though students don’t like the outside referral system, Federman says this model is standard for a college mental health facility, which needs to maximize the number of students seen for treatment. [For more on CAPS resources and funding, see sidebar.]

Of UVA’s 19,200 full-time students, CAPS sees about 1,700 new patients each year, not counting the students who receive care on an ongoing basis.

“We’re good at getting them in,” Federman says. The stigma of going to counseling is on the decline, and CAPS staff make their presence known using the Web and through residence life training.

CAPS staff also spend a lot of time cooperating with other student affairs offices to create a “web” of safety for suffering students. Usually, students with issues like Cho’s would bubble to the surface and multiple phone calls would be made between Federman’s office, Dean of

Students Penny Rue and other administrators.

It’s the students who go under the radar that worry administrators the most.

Federman says, “I just spoke with a student a couple of weeks ago who took a fairly serious overdose and, to her surprise, she woke up in the morning. How many times does that happen out there that we don’t know about?”

National data suggest that as many as 13 out of every 1,000 students attempts suicide. Of the nation’s approximately 18 million college students, that’s 234,000 suicide attempts every year, or 642 attempts every day.

Suicide rates are especially disturbing following the Tech shooting because, as Federman told the Senate committee, “some students become suicidal before they become homicidal…before they act on their murderous wishes.” (Homicidal ideations, by the way, are still very rare. UVA had no such instances last year.)

At UVA, 54 students were hospitalized last year for psychiatric reasons, most of those “suicidal ideation or attempt.” There were 64 hospitalizations the year before, more than any other year. But, with only three successful suicides over the past six years, UVA has less than one-third the expected suicide rate for an institution its size.

Federman says UVA has stayed insulated partly because of a “tight-knit safety net.” But, “I would also say we’re lucky, or we have been lucky.”

“When anything goes awry on campus, parents will sue.”

Other schools haven’t been so lucky, nor their students.

In 2000, at Ferrum College in Virginia, freshman Michael Frentzel had a fight with his girlfriend. A few days later, he sent her a note informing her he intended to hang himself with his belt. The girlfriend showed the note to a resident assistant and college officials, who failed to supervise Frentzel. He hanged himself in his dorm room a few days later. In Schieszler v. Ferrum College, Frentzel’s guardian, LaVerne Schieszler, prevailed in court that a “special relationship” existed between Frentzel and college officials and that the school knew of the “imminent probability” that Frentzel would harm himself. The two parties reached an out-of-court settlement.

Also in 2000, Massachusetts Institute of Technology student Elizabeth Shin, a long-depressed overachiever, set herself on fire in her dorm room. She died in the hospital several days later, her body covered in third-degree burns. Shin had made suicidal threats over e-mail to faculty before her death. Her parents filed a wrongful death suit against MIT for $27 million in 2002. A judge found that MIT staff members “failed to secure Elizabeth’s short-term safety…by not formulating and enacting an immediate plan.” The Shin case was also settled out of court.

Speculation has already begun about the lawsuits to come following Cho’s homicidal rampage at Virginia Tech.

But Sheldon E. Steinbach, a higher education attorney with Dow Lohnes in Washington, D.C., and the former vice president of the American Council on Education, says, “At the moment it seems, from the evidence that has become public, that the university, both in terms of handling a disturbed student and in terms of…the onslaught that occurred later, did everything according to the book.”

He adds, “This doesn’t mean someone’s not going to file a lawsuit.” As Steinbach told Salon.com, “When anything goes awry on campus, parents will sue.”

But legal experts are anticipating a tough road for any attorney looking to hold Virginia Tech liable in the shootings.

For one thing, there’s a key difference between the Virginia Tech incident and those at Ferrum and MIT—Virginia Tech is a public school.

Public institutions are subject to something called “sovereign immunity.” So, suing a public university would be a little like trying to sue the government.

David N. Anthony, chairman of the Virginia Bar Association’s civil litigation section, told the Associated Press, “Our government can make mistakes. If they do, we can’t recover from them unless it falls into a category where they say we can.”

Virginia’s Tort Claims Act allows damages of up to $100,000 for bodily injury caused by state negligence, the AP reports. It would be difficult for any party to sue the state for more than that.

And, even if a skilled plaintiff’s attorney could get around sovereign immunity, it would be very difficult to argue that the university was liable for Cho’s actions, since the law in Virginia treats third-party liability cases conservatively.

As if the lawsuit piece isn’t enough of a pickle, lawmakers are quickly corralling for legislation that would help with campus mental health issues. If it did act, it wouldn’t mark the first time the General Assembly created law as a direct response to tragic campus incidents.

Just last session, the Virginia General Assembly passed such a law. Jordan Nott, a 21-year-old student, was charged with violating codes of conduct and suspended from George Washington University in Washington, D.C., he says, for seeking counseling and checking himself into the hospital for depression. Nott’s friend had killed himself shortly before by jumping from his high-rise dorm. In 2004, Nott sued GWU, saying it violated the Americans with Disabilities Act and other laws when it suspended him, essentially ending his GWU career.

GWU wasn’t the only school using heavy-handed policies to remove depressed students from the campus fold.

The General Assembly responded by passing a law that says Virginia schools c

an’t penalize students solely for seeking help when they’re depressed or suicidal. House Bill 3064 orders universities to institute policies that “ensure that no student is penalized or expelled for attempting to commit suicide, or seeking mental health treatment for suicidal thoughts

or behaviors.”

The law, no doubt intended to let students feel free to seek help, leaves a sour taste following the Virginia Tech shootings. Could such a law have been used to keep an ill student like Cho in school?

Delegate Al Eisenberg of Arlington, the bill’s patron, says, No: “The bill is very clear. First of all, the policies…they’re not proscriptive policies. Each college and university has to decide for itself how it wants to address the problem. Secondly, the legislation makes clear that if a student is a danger to himself or herself or others, or disruptive in any way, the institution can take action… I think that pretty much closes the circle.”

Delegate David Englin, one of many legislators to support the bill, says, “The goal of this legislation is to ensure that kids who need help get help.”

Still, experts caution against quick legislation in the wake of the Virginia Tech shooting.

Steinbach calls such problem-solving “governing by anecdote.” CAPS director Federman says, “I’m uncomfortable with most policy that winds up being reactive.”

“Unless they have a gun and have a plan, it’s not imminent.”

Campus mental health centers, for the most part, do a good job of keeping disaster at bay.

But they can’t do much for students who don’t want help. As has been reported, Cho wasn’t interested in attending counseling. When he was hospitalized in 2005, he denied suicidal ideations with the evaluating psychiatrist, and a judge was convinced he did not require commitment. He was ordered to seek outpatient counseling, which he never did.

According to Federman, colleges have a limited ability to compel students like Cho to get the help they need.

UVA policy says if a student poses an imminent danger to themselves or others, the school can have them hospitalized. While suicidal behavior qualifies as imminent danger, a student can’t be removed for simply making threats. Imminent danger requires intent and a plan. Federman says, “It isn’t just that someone has violent fantasies of shooting others. Unless they have a gun and have a plan, it’s not imminent.”

If the situation is less severe, a student’s behavior could be deemed disruptive under student codes of conduct. Penny Rue, the dean of students, can put a student on interim suspension while his mental health is being evaluated. (Rue could not be reached for comment.)

But, “even then all we can do is assess and provide recommendations to the dean’s office,” Federman says.

While CAPS tries to communicate fully with other student affairs divisions, sometimes patient confidentiality gets in the way. In fact, Federman appealed in the Senate committee hearing for a re-evaluation and clarification of the guidelines for when a university can violate a therapy patient’s confidentiality in dealing with a problem student.

Sometimes, despite oversight of CAPS staff, a student’s situation could simply appear to be less severe than it really is. “There are some times,” Federman says, “when that which comes to [administrators’] attention…may not reach threshold.”

Universities may not be able to take their policies much further without violating students’ rights.

“The ways in which we can control individuals’ behavior when they have their own legal rights as adults is limited,” Federman told NPR.

In Virginia Tech’s case, according to Steinbach, “based on the facts that are available at the moment, they did pretty much everything they should’ve done and that was reasonable to do.”

These are difficult responses to swallow, especially with the images of a crazed killer so vivid in the public mind. Two days after the Tech massacre, “NBC Nightly News” aired a video clip Cho had mailed to their studio. His head shorn to a close buzz cut, Cho donned militaristic attire and filmed a frightening, incoherent diatribe. His deep, monotone voice and heavy brow filled TV screens everywhere as he snarled sentences against rich kids and those who he felt victimized him: “You forced me into a corner and gave me only one option. The decision was yours…now you have blood on your hands that will never wash off. …You thought it was one pathetic boy’s life you were extinguishing.”

The videos were a horrifying cap-off to the worst incident of gun violence in this nation’s history.

But, from Federman’s office at UVA, a scenic campus relatively untouched by tragedy, it’s easier to see Cho less as a monster, and merely as one seriously ill student who did something monstrous.

It’s Federman’s job to look at the big picture.

“Do we have disturbed students at UVA who say and write frightening things?” says Federman. “Yeah, we do. Does it make me as a clinician and an administrator anxious? Yes.”

But, Federman says that on the whole, campus administrators do a good job of managing what goes on in the minds of students, and keeping them safe.

“The fact that [Virginia Tech] had one incident doesn’t mean that we’re failing.”