Artificial intelligence was once the stuff of sci-fi dreams, and though it has been available in some form for many years, 2023 has marked a sea change for AI. New chat bots seem to launch by the day, and backlash has already begun to foment. The “godfather of AI,” Geoffrey Hinton, left Google, warning of the dangers of the invention, and Writer’s Guild strikers have named AI as a threat to their livelihoods.

Advancements in the ease-of-use and sophistication of AI have prompted companies around the world to integrate the most powerful technology of the moment—and maybe for years to come—into their businesses. Now, Charlottesville’s techies are harnessing AI to achieve all sorts of research and marketing goals, but each application comes with its own risks and rewards.

The origins of AI

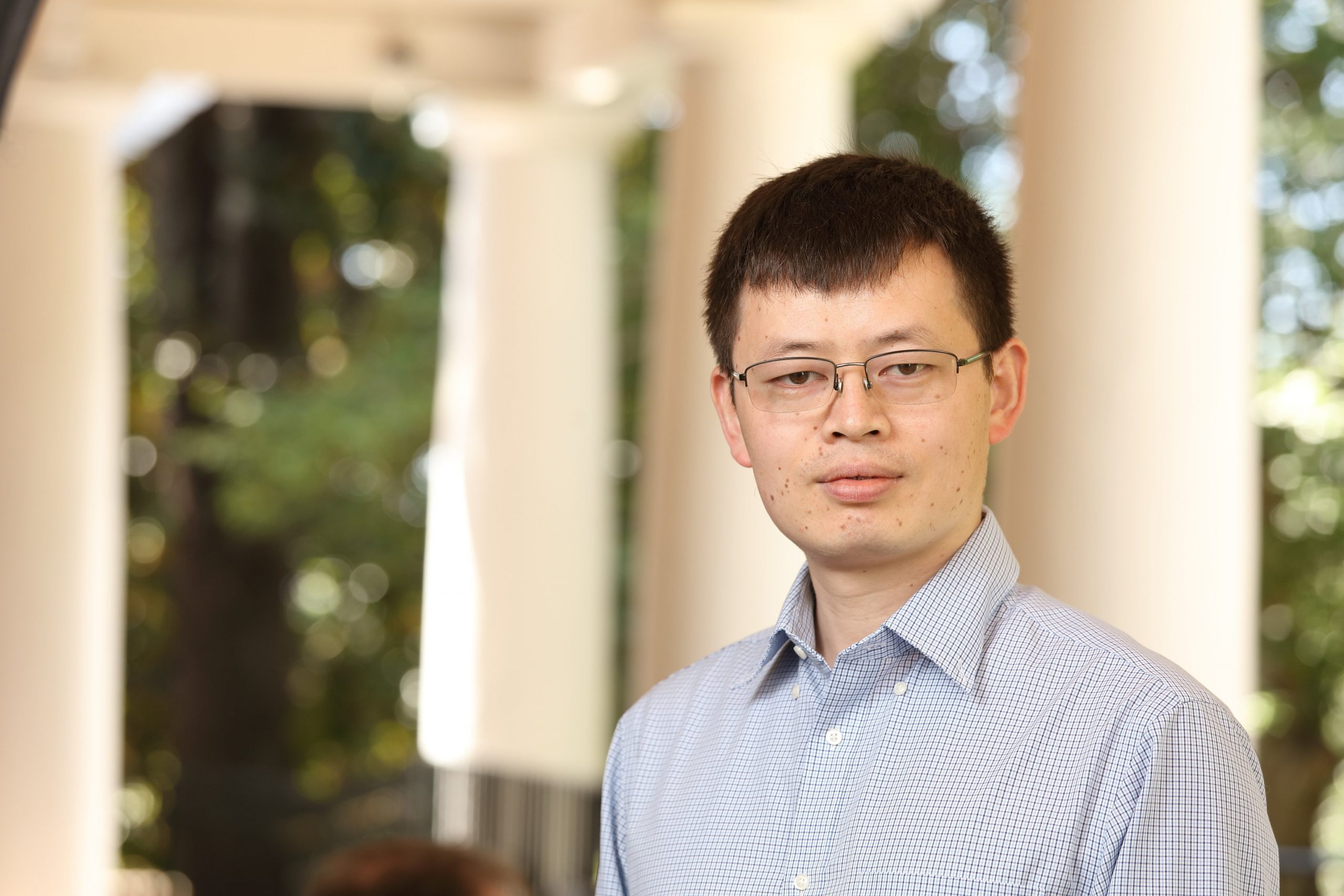

Before AI, machine learning developed. “The goal of ML is to extract patterns from data,” says Yangfeng Ji, the William Wulf Career Enhancement Professor in the University of Virginia’s computer science department. For example, looking at restaurant reviews, a machine trained on data sets can examine the data and figure out which words are related to positive reviews and which words are related to negative reviews. The machine extracts patterns and then predicts something from them, such as whether to add a restaurant to suggested recommendations for a user. “Machine learning is a way to achieve artificial intelligence,” Ji says.

Ji says AI began when people started trying to build and train computers to mimic human-level intelligence and perform tasks in the way a human would, in several aspects. For each aspect, “we try to create a research subject to study it,” Ji says. “To name two examples, we have natural language processing, where the goal is to understand human communication in the natural language. Computer vision teaches the computer to recognize and identify a human face or a different object in an image.”

Charlottesville is a “hub for AI” work and research, says John Elder, who has owned Elder Research for nearly 30 years. He notes that the university here has researchers and professors who train students in AI and machine learning, and many graduates like living here. Elder, whose company creates business value from client’s data, says, “Alumni of our organization have also started or staffed other analytic firms nearby. Charlottesville is very strong, for its size, in data science, just like it is in good restaurants. We also have an abundance of hedge funds and venture capitalists here, which likely further amplifies local innovation.”

Artificial intelligence used by companies reaches far beyond the free version of ChatGPT (which stands for “generative pre-trained transformer”), an assistive, natural-language bot available online through Microsoft’s OpenAI. OpenAI offers more robust products, like the GPT-4 model that is available as an application programming interface, or API, for developers. Other large companies also offer AI, including Alphabet (home of Google), Meta (Facebook), and Baidu in China, so smaller companies can build AI-based applications and services.

AI growth is moving fast

AI usage is growing swiftly in labs and companies globally. Elder says his company brings in “millions” annually for AI-related work.

Market.us estimates that the global artificial intelligence market size was $129.28 billion in 2022, with more than 51 percent of revenues in North America—and growth is estimated to accelerate at a compound annual growth rate of 36.8 percent, to an estimated incremental revenue of more than $2.7 trillion by 2032. While a search for AI revenues in central Virginia or the state didn’t return results, a study by AI-driven website builder YACSS found Virginia to be the 10th most “AI-obsessed” state, based on Google keywords data (Massachusetts was first).

“Analytics, data science, and AI are on a continuum,” Elder says. “They all use experience of known situations and their outcome [data] to better determine actions to be taken for similar new cases. They are ideal for, for instance, finding people who are the lowest risk for repaying loans, or who could be the highest threat to national security. Success marries the speed and accuracy of the computer with the people skills of creativity and understanding of the problem.”

Aiding accurate, swift analysis is UVA’s new School of Data Science. Commerce school alum Jaffray Woodriff, successful in hedge-fund analytics, gave the university $120 million to establish an entire school full of students, from undergraduates to Ph.D.s., looking toward careers in AI and other data analysis fields.

Tobias Dengel, president of WillowTree, a TELUS International company with its headquarters here and more than 1,000 employees worldwide, says, “Over the next 24 months everything we do—from design to development—will be made more efficient using AI tools. Consumers will see this change as every app and website will become a virtual voice-based assistant. To order your favorite coffee or pizza, you’ll just open your Starbucks or Domino’s app and tell it what you want. The entire human/machine interface is about to change.”

Some are wary of that predicted inevitability, however. Artist Rosamond Casey says AI artworks need to stay in the digital world: “Label it as AI art, set up a market for it, but call it what it is,” she says. “Keep it out of the physical world.” With AI making the art, “it appeals to emotion, but large areas of the composition fall apart. Maybe artists being artists will find a way to own AI and make it their tool, and we will all adapt.”

Eric Seaborg, a journalist and author, notes, “The articles I write are based on interviews with experts, and AI doesn’t seem close to being able to do that, so my little part of the world is safe for now.”

But as usage of AI grows, and many leverage its power, some experts’ confidence in its abilities to assume other tasks in society grows with it. Michael Freenor, WillowTree’s principal data scientist says, without hesitation, “I predict every shop will be using AI.”

Locals leverage AI

Elder’s group approaches queries to learn, for example, about people with security clearances by looking for anomalous behaviors—their keystrokes, which doors they enter and exit, and so on. “The question is, ‘How do you create good features out of that vast sea of flowing information, so that you can summarize it in a way to make it clear?’” he says. The model shows only that a person has a certain probability of being risky, fraudulent, or not paying off loans. A model provides a probability (a number between 0 and 100, say), and it’s up to the end user to decide whether to act on the prediction.

Other local businesses, like Astrea, also use AI. Its website describes an “artificial intelligence platform to combine cutting-edge technologies and analytics-ready satellite imagery,” dealing in geospatial data and tools to analyze the data at lower costs.

Drug developer Ampel’s site notes that the company “brings their expertise in basic and translational research, clinical trial design, and bioinformatics together in a new way to develop scalable systems using AI and deep machine learning to improve patient outcomes.” Ampel expects its first product, LuGENE (a blood test that assesses disease state and drug options for lupus patients), to be out this year. ZielBio is also using AI to develop drugs, as is HemoShear Therapeutics. All three are based in Charlottesville.

Sheng Li, a professor in the UVA School of Data Science, primarily directs his AI research to improve trustworthiness. In the concept of machine learning, those in the field define trustworthiness from several angles: robustness, fairness, transparency, security, and interpretability. His team would like to investigate all of these topics, but for now it focuses on robustness and fairness.

One robustness project is fish recognition—gathering data for the U.S. Geological Survey. Researchers are recording unique patterns and markings that stay with individual fish over the years. The recognition data has robustness issues, however, because often the fish are not seen in winter, and by spring and summer they gain size. Such changes will make the model work worse if you only examine data from certain seasons. More frequent data will improve the project, which tracks fish to learn how populations are growing. If individual fish can be recognized, then researchers can monitor the health status of the fish, based on unusual skin patterns, Li says.

WillowTree has an active AI project group, including clients in health care, human resources, financial services, and agribusiness.

WillowTree’s Freenor says his most complex project to date involved a client dedicated to enabling data-driven efforts in diversity, equity, and inclusion. AI can drastically increase productivity across product development, so one assignment that typically takes six weeks was completed in two days. The final product entailed creating a smart database interface for HR professionals skilled in the DEI space but not necessarily at data analysis or engineering. With GPT, natural-language commands such as “What’s the gender pay gap at my company?” allowed users to search for patterns in the client’s own HR database on which the AI was trained.

“It was the first major project we used GPT on,” says Freenor. “It’s the first time in my career that I got giddy with a piece of technology, honestly. It was very obvious. It was so fast and I had it performing in just a couple of hours, which was wild.”

Freenor cautions that with a large-language model like GPT, the first answer isn’t always the right answer, however.

WillowTree found prompting and then re-prompting technology is a good technique, says Freenor. Adam Nemett, WillowTree’s director of brand and content strategy, explains that this kind of “prompt engineering” is vitally important. “If the technology is operating in a world of assumptions, drawing on the massive amount of public information it’s been trained on, it’s going to reflect whatever bias exists in its training.”

“For most use cases a company will want to license and train the AI independently, to make sure the application is analyzing a concrete set of data rather than billions of data points from all of human history. Then you can essentially engineer the prompt to refine itself,” Nemett says. “Just because this technology is powerful doesn’t mean it’s always correct the first time. You still need human experts building and training these models to ensure the privacy of the data and integrity of the system’s responses.” Nemett says WillowTree is well positioned to work on complex, thorny issues because of the breadth of its expertise, from the data scientists effectively wielding LLMs to the engineers and designers building voice-powered AI solutions to the social scientists in their research division staying abreast of the technology’s impact.

UVA’s Ji is working on a system that would make the human user responsible for concluding the correct answer. He wants a system to include three different characteristics for the user’s peace of mind: an answer, an explanation for the answer, and then the percentage prediction that an answer is information used to come to an answer.

Given all of the information, the human user needs to make an educated decision about whether the answer is truthful or whether it is misinformation. “The difficulty is that we have to construct a collaboration, working together with people who may have different views and backgrounds,” Ji says.

Risks of AI technology

Kay Neeley, associate professor in the UVA School of Engineering and Applied Science, teaches a course called The Engineer, Ethics, and Professional Responsibility. Every student in the school must take one ethics course.

“One of the biggest problems is that AI is a very broad category of technical capability that can be used for lots of different things,” Neeley says. “We need to start by saying that generalizing about AI doesn’t make sense.” She calls for people to look at specific AI applications in the context of their use.

“Scrupulous” is a word several interviewees used when talking about businesses that use AI. Businesses must be scrupulous or the information delivered will be unsatisfactory, false, or worse. There can be risk to the brand if the LLM doesn’t provide thorough information or provides incorrect information, or if someone can trick it to obtain information or intellectual property that should not be released. “There is risk to the brand and to those who receive its information, and any of those outcomes is bad from an organization’s perspective,” Freenor says.

Often, those who get the information hesitate to use it. Gartner, a technological consulting firm, predicted that “80 percent of analytics insights will not deliver business outcomes through 2022.” Elder says he is pleased that 90 percent of his clients do use the insights his team provides. “People naturally fear making decisions in a new way. They may not understand the model well enough, or just figure that no one gets fired for doing things the old way.”

ChatGPT, open and available to the public, is astonishing people with how quickly it can produce seemingly-sensible commentary on any subject. That it is public and free may be a real problem, in Elder’s view. “It lies brazenly. I wouldn’t make a business decision based on it,” he says. “It never says, ‘I don’t know.’ It’s often right, always wrong about something, and completely confident on everything.”

Elder challenges: “Ask it something you know a lot about. Like, ask what you have invented and how does it work? It’ll get some things right but then run on about your genius with say, a super-shredder or galvanizing rubber. It badly needs a validation mechanism.” He says he knows a local firm using the public version even now to craft marketing pitches to different types of customers.

Neeley agrees that ChatGPT needs to be used carefully. “There are some limited, humane purposes to which something like ChatGPT can be put,” she says. She gives the “very constructive” example of lower-skilled workers who performed at a higher level in the context of interacting with customers if they were assisted by a capability like ChatGPT.

“In an academic context, however, we don’t have students write essays because someone is going to buy the products,” Neeley says. “We have them write so they develop the capability. The point is the people who are developing or making money off of ChatGPT are not bearing the costs of reconfiguring the system of education, so that it still works reasonably well with this capability out there.”

Students could cheat. Neeley bemoans the lack of accountability on the part of the AI developers, while back at UVA, “we are spending a lot of time figuring out how we are going to deal with this capability. Those are costs that we are bearing.”

One of the biggest risks Neeley sees, however, is that people treat the continued development and use of this capability as inevitable, as if this is something that is going to happen, in which case the question is how we adapt to it.

“The discourse of inevitability is inimical to ethical sensitivity and awareness,” Neeley says. “Ethics is not about what we can do, it is about what we should do.”

She subs in “morphine” for AI. “None of us wants to live in a world without morphine. We don’t give morphine to students and say, ‘This can be used for good and bad things, and we hope you make good decisions.’”

With morphine, we control the outcomes. With AI, “we know we cannot control the outcome, but we know the stakes are high enough that we are going to try to control it, and the role that choice plays,” asserts Neeley. “If we believe we have choice, then we do.”