Eric Clapton

John Paul Jones Arena

Thursday, October 12

music From a conversation with my 14-year-old companion on the way into Eric Clapton’s sold-out concert at the John last week: “It’ll be white kids and rich college students.”

O.K., so maybe they’re not teaching about the Baby Boom in the schools anymore. Sure, Clapton attracts a segment of the music-downloading youth market (and some of them came out for the show), but most of the people pouring into the arena had a little more heft around the belt buckle and a little more jiggle around the upper arm—confirmed rockers from back in the day, long before Clapton looked, uh, experienced and grizzled enough to actually be God. And to satisfy them (and get a hell of a lot of butts out of the seats), Slowhand structured a hits-heavy show, virtually identical to his gig in D.C. two nights earlier (many songs sounded just like the record!). Yet somehow he still managed to promote the values of musicianship and virtuosity that provided the early paving stones for Clapton’s own 40-year path.

What’s his secret? Load up the stage with exemplary musicians, and then step back into the lineup just often enough to make the point that you’re merely one deity in a pantheon, and that, really, if you didn’t know already, lowly humans can only approach the divine because the guitar is god.

And who was chief among its priests last week? Doyle Bramhall II on guitar, Willie Weeks on bass, Tim Carmon and Chris Stainton on keyboards, and Steve Jordan on drums. And the archbishops? No doubt they would have to be opening act Robert Cray—who also joined Clapton and his seven-member band for a couple of numbers, including the rousing encore “Crossroads”—and Derek Trucks, whose slide work on “Anyday” and “Little Queen of Spades” was (as some of the kids in the crowd might have put it) friggin’ awesome! Seriously, the man can coax previously unknowable sounds from his instrument.

Which gets us to the conversation between me and the aforementioned 14-year-old as we left the show, a rejuvenated “Cocaine” still ringing in our ears. Me: “Derek Trucks is unbelievable. I think he’s better than Clapton.” 14: “What? No way. Clapton’s the best. He put that guy in his band.” Touché. —Cathy Harding

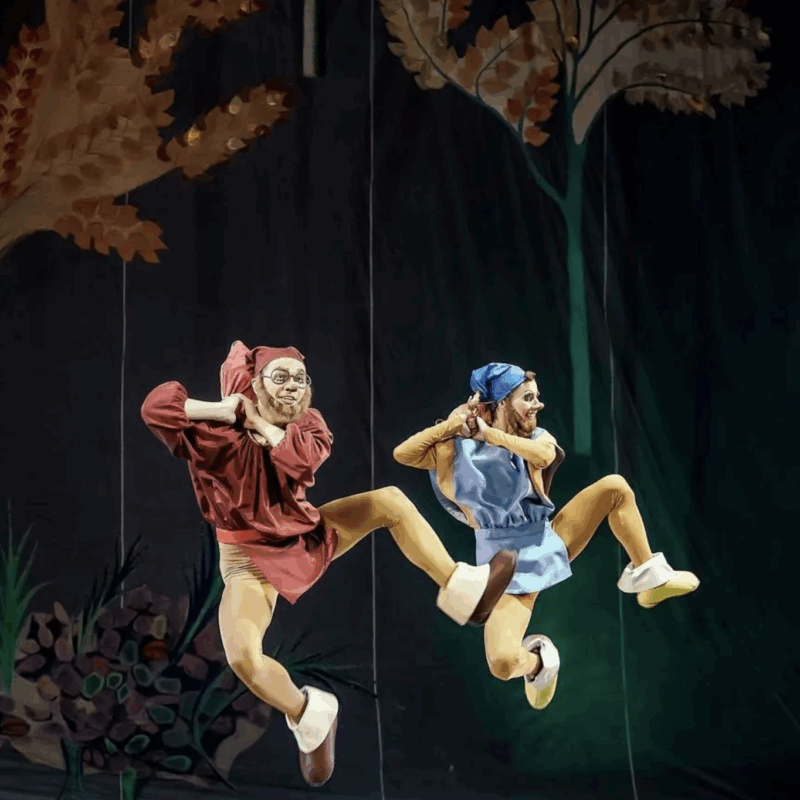

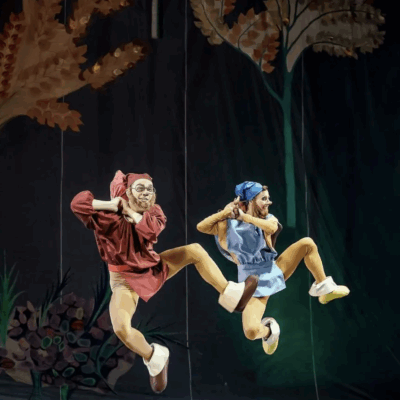

Helen

Live Arts

Through October 28

stage Of the Ancient Greek dramatists we revere today, Euripides is the most fascinating. He was a pacifist and a free thinker in a time when violence and intolerance were the norm. His characters are often anti-heroic, and confront their interior and exterior lives in ways that anticipate modern psychological playwriting. His work is at once teasingly intellectual, wonderfully strange, gorgeously written and crackling with energy. His technique is distinctly nonformulaic. In the case of Helen—one of the few of the almost 100 plays he wrote that have survived—he introduced contrasting elements into the rigid structure of tragedy, creating what we today call the comedy/drama.

Ellen McLaughlin’s modern-English adaptation of Helen is like an extremely liberal translation of the play. It exists on its own merit while preserving shades of Euripides’ poetic spirit, as well as the original structure: a dizzying array of tantalizing ideas and themes anchored by a clear attack on the futility of war.

McLaughlin’s version takes place in a luxury hotel room in Egypt, where Helen (Jennifer Downey) endures a lifeless existence swatting flies and flipping through TV channels while the Trojan War—a fight, in effect, for the right to possess her beauty—rages outside. Besides periodic appearances by her servant (Cynthia Burke), she also has visits from Io (Susan Burke), whose horns are the only remaining evidence that she was once transformed by Zeus into a cow, and from Athena (Linda Zuby, who by day is C-VILLE’s Business Administrator), the goddess who looks down upon mortals as if they were toy soldiers, and, finally, from her husband, Menelaus (Chris Baumer), in a daze over his decision to raise an army to steal Helen back from Paris, leading to the deaths of thousands.

It’s no wonder that Live Arts’ Marketing Director Ronda Hewitt, a standout actor, was drawn to direct Helen. The play, relayed largely in extended monologues, is an actor’s showcase. The cast and Hewitt clearly worked diligently together to make each monologue a deeply felt, multicolored event. Without Downey’s consistently varied emotion in the lead role, for instance, the whole two hours would have been as static as Helen’s hotel room.

Hewitt is also adept at creating an air of unreality that meshes with McLaughlin’s blend of modern and ancient details and tones. Hewitt does this not only by encouraging an acting style that’s a few beats away from realism, but also with concrete techniques like stop-motion and shadow-play.

That said, she’s not afraid to leave much of the text to speak for itself, and to trust the audience to tune into its subtleties. So, if you think that “mentally challenging” really means “mentally taxing,” you might want to spend your money on Jackass Number Two instead.—Doug Nordfors

The Road

Cormac McCarthy

Knopf, 241 pages.

words It’s bleak, depressing and unflinching—it takes the human capacity for hope, crushes it into a tiny ball, and tosses it into the wastebasket of wishful thinking. Which means, basically, that The Road is like any other Cormac McCarthy novel. Acting as a sort of one-two punch in combination with last summer’s brilliant No Country For Old Men, McCarthy delivers yet another world in which human law and morality are absent, in which death permeates every page like a thick ground fog, and in which the entire universe seems poised on the brink of a biblical apocalypse.

What makes The Road unique from its predecessors is that the landscape in this case is not the open prairie or the untamed West, but a blighted, ashy America in which an unnamed holocaust (my guess is nuclear) has wiped almost everyone off the planet. A nameless man and his young son make their way down a nameless road to a destination that’s never quite clear (this is one of those novels where the themes lie in the journey, not the destination). But what a terrible journey it is: an almost relentless plodding through a literal wasteland that calls to mind the final, post-meteor march of the dinosaurs in Disney’s Fantasia. “They passed through the city at noon of the day following,” McCarthy writes. “The city was mostly burned. No signs of life. Cars in the street caked with ash, everything covered with ash and dust. Fossil tracks in the dried sludge. A corpse in a doorway dried to leather. Grimacing at the day.” See what I mean?

What holds this novel together, however—the saving grace that keeps it f

rom descending into a schlock post-apocalyptic thriller—is the bond between father and son, the almost regimented manner of protection that reads like tough love but feels like true love. Their relationship is what provides the reader an emotional home amidst this “one vast sepulcher”—it’s an emotional bond we don’t find in any of the other sparse survivors they encounter. The Road is a story of Darwinian survival, in which the supposedly moral and superior homo sapiens has devolved into just another animal—scrounging for food, fleeing from predators, defending their young with claws extended and teeth bared. There are some tense moments throughout—episodes where it seems things cannot get any worse (and believe me, they always do)—but not for one moment does the reader imagine that this man will leave his son behind to fend for himself.

McCarthy is a stylist unlike any other currently working in American letters; his economic prose makes these fantastic events all the more believable, and his penchant for quick, brutal violence is ever-present (when you’ve got one of the last working handguns in America, you’d better believe it’s going to be fired at someone). Most unremarkable is the blatant glimmer of hope that closes the story. Whether you buy it depends on whether you’re a half-emptied- or half-filled-glass kind of person. As for McCarthy’s glass—well, it seems like there are still at least a few drops left in it. —Zak M. Salih