Half a century ago, Peter Jensen launched Project Censored, in part as a response to how the Watergate break-in was covered. Richard Nixon didn’t censor the initial reporting, but he didn’t have to. The press simply didn’t cover it with any serious scrutiny until well after Nixon was elected. The story didn’t reach the American people when it mattered most—when they could have done something about it directly themselves, before they went to the polls in November 1972.

Reflecting this, Jensen saw censorship as working differently in a democracy than in a dictatorship. He defined it as “the suppression of information, whether purposeful or not, by any method—including bias, omission, under-reporting, or self-censorship—that prevents the public from fully knowing what is happening in society.”

That happened with Watergate, though the truth belatedly came out. And an echo of the same sort of thing happened just as I was writing this half a century later. Six members of Congress who had served in the military or the CIA released a video accurately informing those serving, as they had, that they have the right—and in some cases the duty—to refuse unlawful or unconstitutional orders. President Trump responded on social media by falsely claiming their video message was “SEDITIOUS BEHAVIOR, punishable by DEATH,” but The New York Times relegated the story to page 16, with a headline that didn’t mention Trump’s call for their execution. “No wonder Trump thinks he can get away with anything,” said Mark Jacob, a former top editor at both the Chicago Sun-Times and the Chicago Tribune.

This was only a faint echo of what happened with Watergate—especially given the Times’ diminished gate-keeping role. But those echoes are everywhere around us, every day. That same dynamic of suppression of information by under-reporting and self-censorship is constantly at play, with the same consequence of preventing the public from fully knowing what’s happening in society—particularly in time to do something about it.

For half a century now, Project Censored has been bringing these omissions to light, and while each story highlights a particular omission, they are often complex and interrelated to each other. There’s a perfect example in this year’s top censored story: ICE solicits social media surveillance contracts to identify critics. Government spying on, suppressing, and even criminalizing its critics goes back at least to World War I as a systematic endeavor, but new elements have intertwined with it over time. Racial targeting, private contracting, and omnipresent surveillance technology are all present in this most recent example, and are routinely censored in other settings as well.

It’s also an example of systemic abusive policing—racial targeting is involved in stories number three and four, regarding systemic exploitation of Native Americans and targeting of pro-Palestinian activists, respectively.

Stories four and five involve tech surveillance in different ways, not just targeting activists but also systematically blocking data privacy protections for everyone.

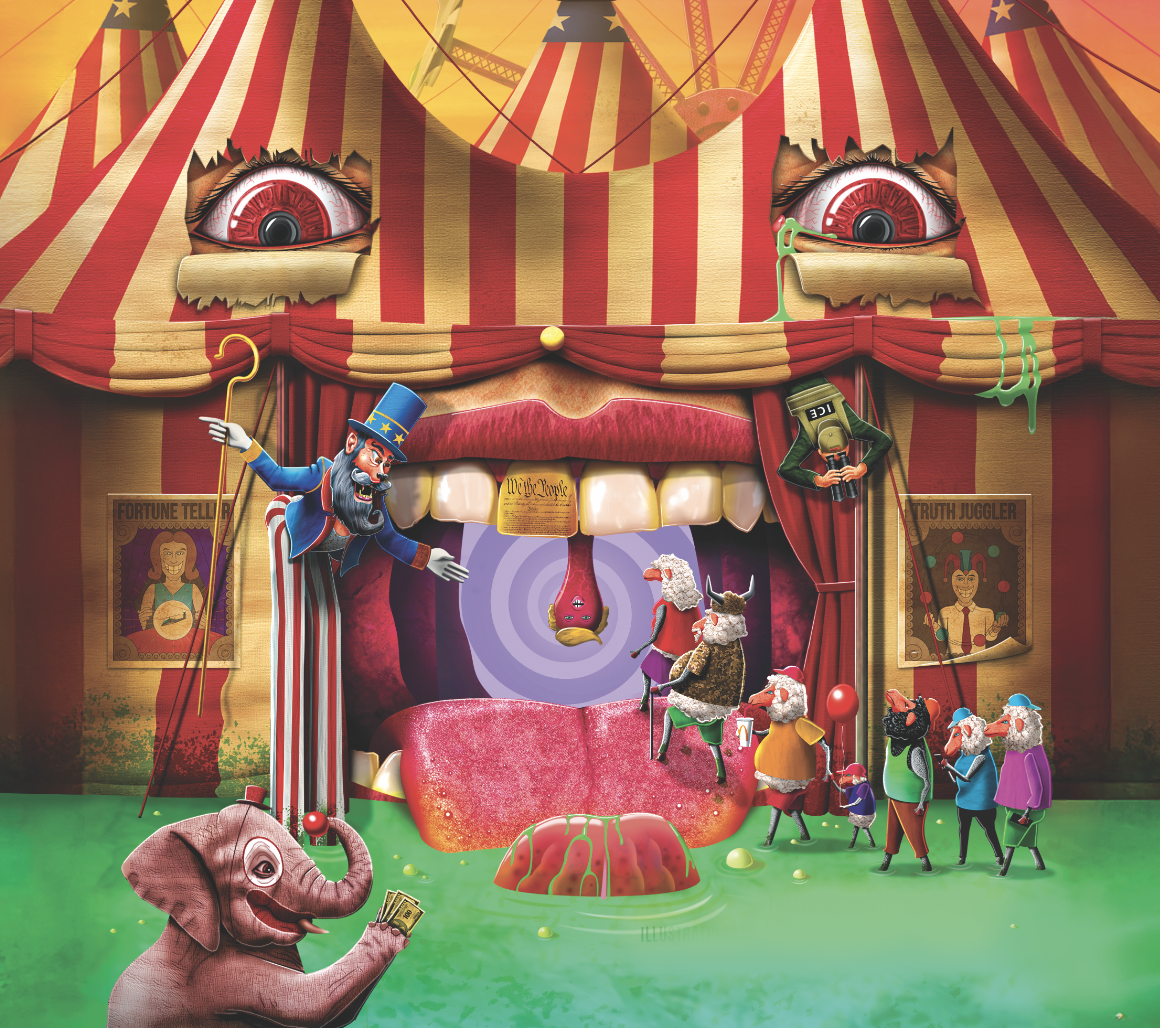

Project Censored’s list is about a different way of seeing the world if systemic censoring was stripped away. Here, then, is Project Censored’s half-century anniversary list, so you can see for yourself what that means.

ICE solicits social media surveillance contracts to

identify critics

In February 2025, Techdirt’s Tim Cushing reported on Sam Biddle’s Intercept investigation into a new ICE bid solicitation seeking private contractors to “monitor and locate ‘negative’ social media discussion” about the agency. The request, also covered by The Independent, appeared as the agency prepared for a more aggressive role under the returning Trump administration. ICE’s plan, Biddle wrote, could pull “people who simply criticize ICE online” into its surveillance dragnet.

Biddle noted the solicitation was “nearly identical” to a 2020 request that resulted in a $5.5 million contract with Barbaricum, a Washington-based defense and intelligence firm. But the new version, arriving amid ramped-up enforcement rhetoric, signaled a broader threat. Cushing observed that ICE justified the program by citing increased risks—yet provided no evidence.

The scope of potential targets is massive. Social media criticisms of ICE number in the millions, but contractors would be required to assess users’ “proclivity for violence” using “social and behavioral sciences” and “psychological profiles.” After scraping personal details—Social Security numbers, addresses, affiliations—contractors would deliver ICE dossiers containing photos, partial legal names, birth dates, education or work ties, and identified family members. The request also sought facial recognition tools capable of scanning the internet for additional information tied to a subject.

Although framed as a safety measure for ICE employees, Cushing wrote that the document “makes it clear ICE is looking for tech that allows it to monitor people simply because they don’t like ICE.” The First Amendment implications, he added, are unmistakable: the government should not monitor social media users to quantify criticism, especially when it conflates negativity with threats.

ICE’s digital surveillance ambitions are not new. Past investigations revealed fake ICE social-media profiles, entrapment schemes, and systems designed to flag “derogatory” posts.

Water scarcity threatens 27 million people in the United States

Nearly 30 million people in the U.S. live in areas with limited water supplies, Carey Gillam reported for The New Lede in January 2025. The finding comes from a first-of-its-kind U.S. Geological Survey study assessing national water availability from 2010 to 2020, including quality concerns. With climate change worsening droughts, floods, and contamination, the crisis is expected to deepen. Project Censored also highlighted two ongoing threats: saltwater intrusion and PFAS “forever chemicals,” linked to cancers, liver disease, and birth defects.

USGS Director David Applegate warned of “increasing challenges to this vital resource,” noting that socially vulnerable communities face the greatest risks. Gillam reported widespread pollution in waterways across the Midwest and High Plains tied largely to industrial agriculture runoff. USGS found “substantial areas” of major aquifers—supplying one-third of public drinking water—contaminated with arsenic, radionuclides, manganese, and nitrates. Low-income, minority, and rural, well-dependent communities face disproportionate exposure.

Project Censored cited worsening shortages in Texas due to drought, aging infrastructure, and international water disputes, and in Florida, where population growth and groundwater overuse have collided with climate-driven storms and droughts. In Virginia, massive data centers consume up to 5 million gallons of water daily, Grist reported, straining already depleted aquifers.

Globally, the situation mirrors U.S. trends. A joint U.S./UN assessment, Drought Hotspots Around the World 2023–2025, described current conditions as “a slow-moving global catastrophe,” with 48 U.S. states experiencing drought in 2024—the highest number on record. Meanwhile, The Guardian reported that the Trump administration ordered the closure of 25 federal water-monitoring centers, undermining the nation’s ability to track shortages.

Indigenous communities in the U.S. underfunded and exploited by federal and state governments

A series of 2024–25 investigations by ProPublica, High Country News, and Grist revealed how federal and state governments continue to underfund and exploit Indigenous communities—coverage largely ignored by corporate media. Matt Krupnick (ProPublica) documented the chronic underfunding of tribal colleges, institutions created in the 1970s to serve Native students harmed by generations of violence, dispossession, and cultural erasure. Although Congress set funding at $8,000 per tribal student in 1978, adjusted annually for inflation, the government has never met its obligation. Since 2010, per-student funding ranged from $5,235 to just under $8,700—far below the roughly $40,000 it would be if federal commitments had been honored—totaling a $250 million shortfall. Under the Trump administration, conditions worsened as at least $7 million in USDA grants for tribal colleges were suspended.

Meanwhile, a joint High Country News/Grist investigation showed how states profit from “trust lands” located inside reservations. These lands, often seized during the 1887 Dawes Act Allotment Era, generate millions through grazing, logging, mining, and oil and gas production—funding state universities, prisons, hospitals, and schools. Earlier reporting traced this system to the 1862 Morrill Act, which granted nearly 11 million acres taken from nearly 250 tribes to states to build land-grant universities.

The new investigation mapped 1.6 million acres of state-managed trust lands within 83 reservations across 10 states, revealing how state control undermines tribal sovereignty and jurisdiction. In some cases, tribes must lease back what was once their own land—an estimated 58,000 acres—paying the state for agricultural or grazing use. One notable exception is the Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes in Montana, which secured the return of nearly 30,000 acres through a 2020 water-rights settlement.

Corporate media coverage of these injustices remained minimal, limited mostly to stories about Trump-era layoffs that failed to address the deeper, long-term history of governmental neglect.

Meta undertakes “sweeping crackdown” of Facebook and Instagram posts at Israel’s request

Since Oct 7, 2023, Meta has executed a massive censorship campaign on Facebook and Instagram, removing or suppressing posts critical of Israel or supportive of Palestinians, Drop Site News reported in April 2025. The report called it “the largest mass censorship operation in modern history,” based on internal Meta data provided by whistleblowers and confirmed by multiple sources inside the company.

Meta reportedly complied with 94 percent of takedown requests from Israel—the single largest originator of content removals worldwide—affecting an estimated 38.8 million posts. While most requests were classified under “terrorism” or “violence and incitement,” the complaints all used identical language regardless of the content, linking to an average of 15 posts each without describing the posts themselves.

The campaign disproportionately targets users from Arab and Muslim-majority nations but has a global reach, affecting posts in over 60 countries. Drop Site News warned that Meta’s AI moderation tools are being trained on these takedowns, potentially embedding this censorship into future automated content decisions.

Project Censored noted that the Council on American-Islamic Relations condemned Meta’s actions, stating, “Meta must stop censoring criticism of the Israeli government under the guise of combating antisemitism, and Meta must stop training artificial intelligence tools to do so.” The report also cited the Committee to Protect Journalists’ findings that Israel controls coverage of its military operations.

Although independent outlets such as ZNetwork and Jewish Voice for Labour republished the Drop Site News report, no major U.S. newspapers or broadcast outlets had covered the story as of July 2025. Meta shows no signs of ending the censorship initiative, leaving critics concerned about the implications for free expression and the global reach of government-directed social media moderation.

Big Tech sows policy chaos to undermine data privacy protections

Big Tech companies are actively attempting to undermine consumer data privacy laws, using tactics reminiscent of Big Tobacco in the 1990s, Project Censored reports. Jake Snow documented this in Tech Policy Press and the ACLU of Northern California in October 2024.

Snow outlined a three-step strategy. Step one: “Respond to a PR crisis with a flood of deceptive bills.” Just as tobacco promoted “smoking sections” to weaken bans, Big Tech floods Congress with industry-backed laws that replace meaningful privacy protections with weak alternatives. Snow cites a 2021 Virginia law drafted by an Amazon lobbyist as “just what Big Tech wants.”

Step two: Complain about the “patchwork” of state laws, portraying diverse regulations as chaotic or unworkable. Tobacco did this in the 1990s; today, tech lobbyists repeat it, even creating websites like United for Privacy: Ending the Privacy Patchwork.

Step three: Use federal preemption to erase state laws and block stronger local legislation. While federal law could set a floor—like the federal minimum wage—Big Tech pushes it as a ceiling, limiting grassroots influence. Snow notes that states and cities historically drive real change. California, for example, enshrined a privacy right in its 1972 constitution, offering protections against modern abuses. Once state legislatures are sealed off, communities with limited access to Congress lose power.

These tactics are not hypothetical. The House version of Trump’s controversial “Big Beautiful Bill” included a provision shielding tech companies from state lawsuits for a decade over negligence, privacy violations, or AI misuse. Though removed by the Senate, similar efforts are expected.

Project Censored noted that while outlets like The New York Times and Time have reported aspects of Big Tech lobbying, no corporate coverage has fully captured the scale, coordination, or historical parallels Snow identified—leaving much of the strategy’s impact unexamined.