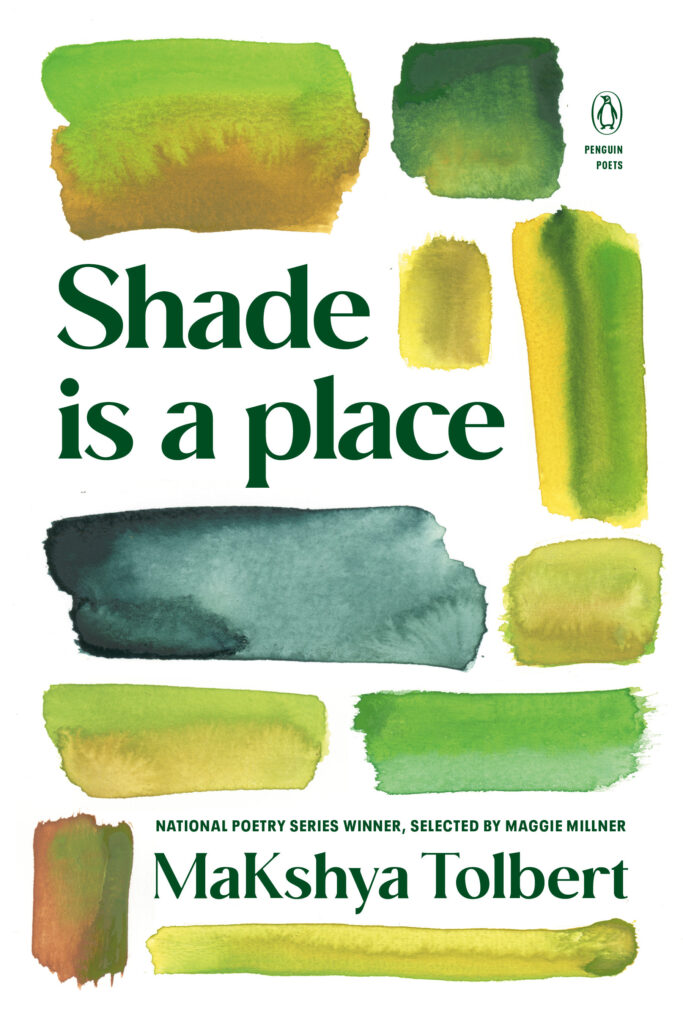

MaKshya Tolbert practices poetry and placemaking in Virginia, where her grandmother raised her. She is the 2025 Art in Library Spaces artist-in-residence at the University of Virginia and co-stewards Fernland Studios, an open-ended studio insistent on rest, rejuvenation, and reciprocity as a core compositional practice. Tolbert was the 2024 New City Arts Fellowship guest curator, and served as 2024-25 chair of the Charlottesville Tree Commission. She has received support from the U.S.-Italy Fulbright Commission, New City Arts, Community of Writers, and Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects. We recently discussed her debut book of poetry, Shade is a place, which was published earlier this month.

C-VILLE: This collection grew out of work you undertook during your artist residency at New City Arts in 2023, specifically the interactive, community shade walks that you led on the Downtown Mall during that time. In the poem, “Shade walk: ‘a life in rehearsal,’” you invite the reader along in these explorations, as people get to know the Mall’s willow oaks, declining in numbers even as you work. How did these shade walks inform or alter your understanding of your writing and the project overall?

MaKshya Tolbert: My shade walks were firstly an invitation for gathering among the Mall and its trees, as they turn. Getting to “be an invitation” for building an intimacy with the environment was as much for my own sense of place as for the possibility of inciting or widening that in members of the public who came along. Some more than once. And, as you know from the year we spent together in residency at New City Arts, I both wanted a social practice and also a place to rehearse—or practice—a different kind of relationship with each other. More tenderness.

Second, looking up and down at willow oaks and at each other—while also looking at my poem drafts—was an opportunity for revision. Sometimes a shade walker would make an observation that resonated with or troubled my own sense of attention. Many nights were spent with me at home trying to listen to the walk I had taken that morning.

If you’re reading this, and you shade walked with me: Thank you for your attention, which was so gracious for mine. The shade walks also gave me a container to rearrange my increasingly wayward relationship to movement, which led to a rearrangement of my poetics.

Those patient walks inspired me to write patient poems and soon enough, I was writing notebook-length, Bashō-style “haibun” (a Japanese poetic form that links prose and haiku) and thinking of the shade walks as an ambivalent practice always oscillating between a deepening “sense of place” as much as a choreography for movement. The shade walks gave me a sense of my own inner life as locomotive, this moving place inside me. And I wondered how that inner quality—of both place and movement (locus+motive)—could support the walks as both an inner directive and a wider invitation.

In that same poem, you write, “I thank myself for what I have been able to love: for not needing to give the willow oaks new names, for coming back all these mornings to be with trees for what they are. I start with study, limb walk toward self-study.” In this, I hear an expression of a practice—artistic, creative, meditative, and otherwise—that aligns with the themes of self-pruning, self-repair, and self-embodiment that you weave in and work at throughout the book. What evolution and adaptation has taken root in your own life as a poet and artist, through the creation of this collection?

The epigraph for this book, by Amiri Baraka, reads:

What I thought was love

in me, I find a thousand instances

as fear. (Of the tree’s shadow

winding

This project has ruptured the writer and the person I thought I was, as well as many of the stories I have about myself, and others. The necessary grief associated with loosening my grip on how I saw myself set me up for a project that I hope is as surprising as it is heartbreaking.

Shade is a place is aspirational, in many ways. I believe I wrote a speaker with more grace and a deeper attention than I have. Certainly with more appetite. That’s why I describe these poems—and shade—as both blueprint and archive, like many “places.” I was trying to admit to myself how great the distance felt between my speaker and me, while also trying to practice poetry and ecological attention as tools that could help close that distance.

I appreciate your curiosity about “adaptation,” which is an entry point into inquiries that run throughout Shade is a place, and beyond. My trying at what it would be to “adapt” both to what’s coming and to what’s already here, in terms of living under extractive economies and the duress that comes with doing so. In my life that was less public and shadeful, I was hiding just how great my needs for relief were: The time I spent with trees and with people talking trees gave me so much to do when I couldn’t look at myself. I could start with trees and their stresses, I thought. So I did.

I’m in a place these days where I can read about what I was going through in a way I couldn’t when I began working on Shade is a place. There’s a sentence I keep thinking about from my recent reading, about “closing one’s body off from exchange with the environment.” What began as wanting to save trees, from that more closed-off position, eventually gave way to a motivational world where arboreal relief (shade) morphed into an inner sense of relief (perhaps akin to being able to hear one’s breath). What’s taking root is a more porous exchange with my environment. Shade is a place offered me a method to loosen myself from what felt like an ecological trap so that as a poet and person I could shade walk with a more openhearted gait amid the flux—”in the middle of things.”

The “Ways to Measure Trees” series of poems suggests the growing experience with classifying trees that you developed over time. How would you describe your relationship to trees before you started this work?

That trio of poems is really exciting to me because I watch the poems shift not only in their physical proximity to trees—each level asks for more closeness and less distance than the one before it—but also in the sequence’s capacity and commitment to practice. Poetry—and shade trees—have given me a place for practice and to also practice practice.

Before I began this work, my relationships to trees were a bit chaotic. On the one hand, I was starting to learn to prune fruit trees—mainly apples and pommes—and found myself jumping up and down at bare trees. Because I could finally see them in their form, and I wanted to care for that. I told myself it really was a question of their integrity, and mine. On the other hand, I had never (and still have not) climbed a tree. I didn’t think too much about that when I was writing. But on a long flight recently, a man and I began talking about his son’s fear of trees and I found my own fear rearing its head. I’d always just thought “I was meant to be on the ground” and realized—after writing the book—that the ground is just where I have let my feet go. This is what I mean when I say that the book and its practices have really pushed my story about myself. In that way, it is not only a blueprint but also an archive of many attempts at living.

The closing work in the book, “Shade notes,” reads like a record of your creative process or a commonplace book, dense with the individual branches and altars of inspiration, information, and consideration that went into the collection. How did your process for writing this section differ or align with the other poems in the book?

“Shade notes” began as a long poem that wouldn’t stop bothering me. Both in that the poem compelled me to keep working on it, yet also bothered me too much to see all the way through. What’s coming up for me about its form and process is a bit anecdotal. I was instructed a few years ago to “write from the body,” in conversation with Hélène Cixous’ essay on écriture féminine (women’s writing), “The Laugh of the Medusa.” I did the assignment. Later, my professor wrote a note to me that I didn’t follow the instructions. I didn’t know what she was talking about!

Two years later, and after two years of some much-needed professional treatment and care, my appetite was stirring again. I went back to the Cixous essay about “writing from the body,” and felt as if it were the first time that her words were entering me. To think I’d never heard them before.

I realized then how far from myself I had been in the years I spent writing plenty of Shade is a place—how much I needed to “take up the space” of myself again. Which lends itself well, I hope, to placemaking and environmental poetics. To a renewed commitment to embracing one’s capacity for exchange with one’s environment. And I thought the infrastructure of that failed long poem—which isn’t so far from the walks themselves, in terms of the stops—could instead be a practice in spacetaking and spaciousness, or in filling myself up again: with study, with breath, with shade.

So I try to end the book with one more walk, with everyone but always with my full self. The contour line that bisects the piece’s pages is one of many walks I took along the Mall, and which I’m glad gets to be somewhere in this physical book.

It feels important that you use “shade walk” as both a noun and a verb, much like how the word “shade” itself takes many forms and suggests sundry interpretations. In one poem, you write, “The more we shade walk, the more my life branches out before me.” What is your hope for the ways that shade walks and Shade is a place will live as both noun and verb in the lives of people and trees?

My initial curiosity with this project—before there was even a book to work on—was to go see about ‘shade and its properties’ and to even seek out “shade without property.”

I wanted to see what shade could sound like, through me. Then I realized my questions about relief and stresses—trees and my own—lent themselves to constant surprises and turns that have become a social practice, an incitement for a more equitable and mutual canopy, an installation, a series of walks, a book.

There’s something about Shade is a place having a morphology that lends a grace to how often it changes. And that it changes. One of many intentions of Shade is a place is that the book might be an object or tool that helps us mark, practice, and yield to what it is to live only for a time—to be transient. I find that writing these poems as our trees’ bark thickens and thins is helping unveil a latent courage beneath my own armor. I wonder if the book can be that blueprint or archive for anyone else, even if only for a moment?

A little hope note: I am drawn to the hope Mariama Kaba describes learning from a nun, this “grounded hope that was practiced every day,” Kaba recollects. When I think of Shade is a place as verb, I think of how much shade’s animacy and my trying to move along the shade has revived my capacity for attention. I’m moved by shade walking and these shade studies as invitations to practice that groundedness. The more I walked—alone and with others—the more I saw my time and poems working toward some form, or choreography.

For turning, of course: We will keep planting trees and we will keep losing them. Poems, too. But also for learning to quiet or slow down enough to hear my own breath, or appetite, again. It might be Shade is a place as noun is a kind of “score” and the notion as verb is what happens when it comes to life. In rehearsal, or practice—call it what you want.

I’m bewildered about this project, which is why it keeps me so entertained, I bet. What I long for more than anything is to be an invitation for practicing that grounded hope, with our literal bodies—each of us deciding how that looks for us. And to offer a process for doing so that is both among the environment and also moves at the earth’s pace: in relation, in flux, of course in tension, and for the time it takes. Dies back, comes back again—each time a little bit its own.

Will you be leading any future shade walks?

I never got used to the brooms. When those first nine dying trees were felled, I never got used to how much sweeping arborists did. Like my grandmother, who raised me, they were always “cleaning as they go.” The more time I spend with trees and with myself, the more the gesture of sweeping comes along. I feel there is so much tending to do as my grip on myself and my environment loosens. And so much—in, around, and beyond me—wants to be touched or moved or cared for. So I’m following the capacity for tenderness rather than tension. I’m working on a walk that follows such a mood, where I can use my body to make room for more. Susan Raffo, of her own long walks, writes, “Walking is not slow enough.” And I’m finding that true in the walks I took and the ones I wrote. It may look like sweeping. I’m always thinking about how else to walk, how else to “be an invitation,” as a friend puts it.

Shade is a place came out on November 4. We strolled the Mall early that evening, in celebration of what you all have helped me to make. As always—and with the exception of the “Shade notes” that close the book, we took that east-west walk along [landscape architect Lawrence] Halprin’s Downtown Mall. I had New City Arts’ incredible and ongoing support to make sure it could all happen, and then we celebrated the book as the next episode in the wayward saga that is Shade is a place.