There is a $25 million fine for bumping into John Hunter’s World Peace Game, the staggering, multilevel roleplaying game that stands 4′ tall near one side of his Venable School classroom. Curtain Calls (who is desperately stuffing his mattress with every spare dollar he can find for a ticket to see the Hives at the John Paul Jones Arena—see Feedback) cautiously follows Hunter around his game board. Then Hunter—dressed in a rich blue robe, his voice soft as if swathed in the same material—reaches out. And. Pushes. The. Structure.

After helping Curt to retrieve his stomach from his tonsils, Hunter grins and explains that he structured the four platforms of play—water, land, sky and space, each divided into four segments, up for grabs among four countries run by Hunter’s fourth grade students—to withstand a few bumps.

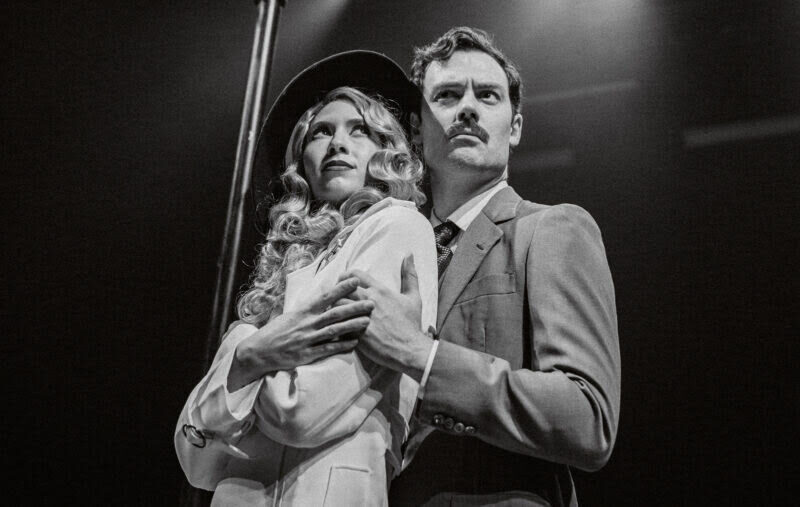

Comprised of hundreds of pieces and four stacked, overlapping levels, John Hunter’s World Peace Game puts students at Venable School to work solving oil disputes and global warming. “You can do anything you want to in the game,” says Hunter. “If you can deal with the consequences."

|

“But it’s only been bumped 10 times or so in 30 years,” he adds with a laugh.

Thirty years’ time has also seen a lot of structural changes to the game, originally a single-level board game created by Hunter for a lesson in African studies at a Richmond school. Hunter has refined the playability of the game, as well: A range of grade levels from high school to fourth grade (and “a few third graders,” says Hunter) have played the game.

Hunter’s class of students that participate in the World Peace Game have a few months to resolve a list of crises that they inherit from previous administrations on their first day—tensions across religious and geopolitical lines that weave with environmental disasters spanning four countries with interconnected histories.

John Hunter explains his World Peace Game. |

If a classroom resolves each conflict they receive at the start of each school year and every country’s asset value increases by the year’s end, the game is won. In 30 years, only one class has ever failed to find world peace. Hundreds of pieces from multiple countries litter the board.

“Every country,” says Hunter, “is in conflict with every other country on every level at the start of the game.” Curt reiterates—these kids are in elementary school (a time CC thought was reserved for kickball and clay).

Last year, a film crew from Chris Farina’s Rosalia Films shot upwards of 50 hours of high-definition digital film that Hunter and Farina hope to screen on a local PBS affiliate before working up the chain at PBS for more screen time; both Farina and Hunter are engaged in fund-raising efforts now.

The prophet

From the Korean War to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, from Alabama to California to Arizona to Virginia. From one end of the Downtown Mall to the other, then back.

“There are many things that make Charlottesville a good place—for me,” says Uriah J. Fields, and Curt makes sure that he is hearing right from the man who lived in Los Angeles during the Watts and Rodney King riots. When CC asks for an example, Fields says, “Less crime.”

Fields may be most recognized locally for the placard he wears around his neck, a sign that lists the current number of American lives claimed since the start of U.S. involvement in Iraq. Today, his sign reads “WHY? 3,799+. TAPS” across his green button-down shirt; his eyes are blue and bright beneath his white eyebrows and lined, dark skin.

And while this sign carries a brutal and straightforward message, Fields is optimistic. In his latest book, The Saint Troubadour: Speaking and Singing Truth and Love, Fields includes a span of writings (“Poems, letters, essays plus!”) and subjects beyond that which he wears around his neck (citing “Love!” and “Romance!” his head leans back slightly, eyes skyward).

The Saint Troubadour (available on PublishAmerica.com and Amazon.com), says Fields, is also a memoir and a work of philosophy, building on ideas that Fields has refined for years (including what he calls his “situational morality” and his “Mutuality Warrior,” a person that Fields describes as being a citizen within society that preserves his or her individualism).

“And it’s about consciousness,” says Fields. “I don’t think anyone could read it without having their consciousness raised.”

Fields speaks to Curt with endless hope and in proverbs. “History is too often used as a hitching post, not as a sign post.” “My life isn’t disorganized, but it is unorganized—I like to move with my intuition.” Each day, Fields says, he wakes and repeats a line from Khalil Gibran: “Awake at dawn with a winged heart and give thanks for another day of loving.”

Before parting, Fields passes an envelope of poems and songs to Curt, opening one and letting his voice do his marching for him, seated, singing.

Patting our backs

On the mailing list for Live Arts? You may’ve recently received a snazzy, pleasantly readable and beautifully designed newsletter detailing a stellar season.

Curt’s interest in finding the designer took him on a long climb—specifically, upstairs to C-VILLE designer Lian LaRussa’s desk. Pick up a copy at Live Arts and check out artistic director John Gibson’s thanks to LaRussa on the inside cover.

And, while Curt is yacking about C-VILLE: Head to the Music Resource Center on Saturday, October 6, to watch Curt’s mild-mannered alter (or “taller”) ego, Brendan Fitzgerald, participate as a judge in the Virginia Teen Idol Talent Competition, presented by Lifeview Films (see listing, page 42). The night’s winner will receive 500 CDs featuring their original tunes, art included. William Hung impersonators need not participate.

Got any arts news to share? E-mail curtain@c-ville.com.