The UVA Patent Foundation recently announced that university inventors received 32 U.S. patents in 2010—a record number, according to Miette Michie, interim executive director of the foundation.

“We like to look at it as a validation of the novelty and the utility of the inventions we have coming out of research here at UVA,” says Michie.

|

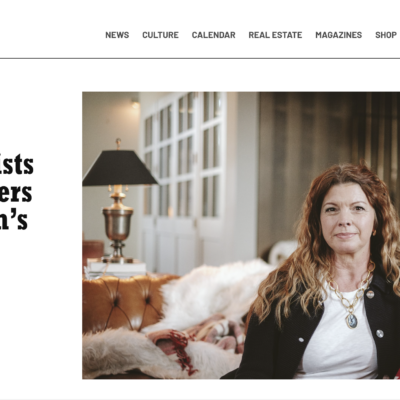

Miette Michie, interim executive director of the UVA Patent Foundation, called the foundation’s record number of patents issued a “third-party validation of scientific innovation.” |

However, that number of inventions seems to be slowing. Each year, the UVA Patent Foundation releases its annual report, which lists the number of provisional patent applications filed, royalty revenue from UVA inventions, and the number of invention disclosures by UVA inventors. Since Fiscal Year 2007, the number of invention disclosures has dropped from 184 to 139—a 24 percent decline.

There is no explicit link between the number of inventions disclosed and the number of patents issued annually. A number of the new UVA patents were issued for applications filed three or four years ago. Additionally, UVA filed more provisional patent applications in 2010 than in 2009, despite fewer invention disclosures.

But one wonders whether a decline in invention disclosures could negatively impact the budgets of UVA’s most innovative laboratories a few years down the road. Patented inventions earn royalties, which propel the next round of studies by aspiring inventors. In FY2010, UVA patents generated roughly $6.2 million in revenue—down from $7.2 million in FY2009, but a sturdy number compared to recent years. Of that $6.2 million, roughly half was distributed between UVA ($1.8 million) and the inventors themselves ($1.2 million). The rest, says Michie, covers the operating budget for the foundation, which employs 16 and might pay anywhere from $10,000 to $20,000 in fees per patent application.

Last year, Dr. George Gillies, who teaches in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, received two patents for targeted catheter systems. He filed his patent applications in 2005. Patent royalties, says Gillies, are “primarily responsible for funding much of my part of the work on our latest efforts to advance instrumentation for cardiology and neurosurgery.”

Michie attributes the decline in disclosed inventions to a decline in government funding and grant sources. “Everyone’s struggling a little bit with writing grants and trying to find other sources of funding, which takes away their time to think about disclosing an invention,” says Michie.

Of course, being an inventor means taking constant aim at a moving target. The rate of successful innovation may be moved by finances, but it’s also moved by—excuse the pun—currency. Different inventions may demand different times.

Dr. Boris Kovatchev, a professor in UVA’s Department of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences, says his lab filed more inventions and received more grant awards in 2010 than ever before. And Dr. Gillies maintains that grants have always been difficult to come by, and the challenges to inventors remain unchanged.

“I believe they are the same as they have always been,” says Gillies. “Appropriate use of one’s imagination and experience to find the right idea to solve a particular problem.”

/8910_photo_1_high_res.jpg)