Danzy Senna’s latest novel, Colored Television, tells the story of Jane, a novelist and tenure-track professor, and her husband Lenny, a painter and teacher at a Los Angeles art school that’s described as “a white hipster playground.” As a self-identified mulatto woman married to a Black man, Jane is abundantly aware of issues of race and class in her life. She uses her creative work as a place to examine these dynamics, root herself in a history that is not strictly Black and white, and attempt to make a place for herself and her multiracial family. However, while her writing is entirely focused on her interest in mulatto history and identity, Lenny’s paintings are abstract, one art critic noting that, “You’d never know the painter was Black.” This highlights a core tension within the book.

Colored Television explores and grapples with multiracial identity and the empty promise of representation, class differences and economic aspirations, the social expectations placed on women—especially Black women—and the potent ways that these experiences can combine to foster imposter syndrome and shame.

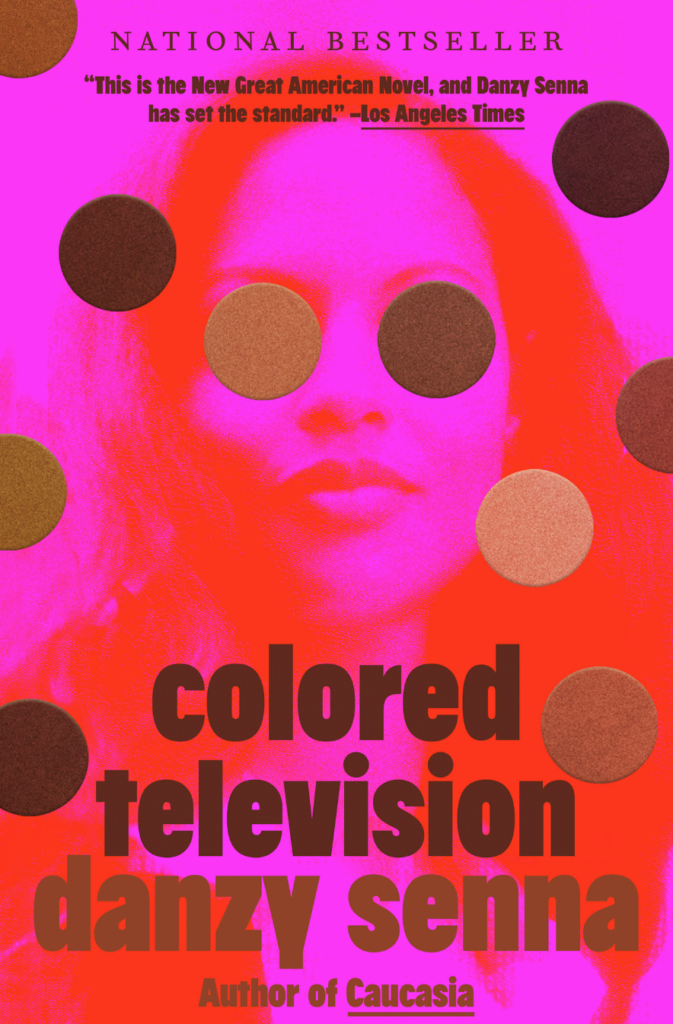

For those familiar with Senna’s previous work—especially her debut bestseller Caucasia, which has been translated into 12 languages and was named a Los Angeles Times Best Book of the Year in 1998—the themes will sound familiar, as her previous work also explored race and multiracial identity, class, and family, often with autobiographical details.

Senna, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Southern California, is the author of six acclaimed books. She has received the Whiting Award and the John Dos Passos Prize for Literature, among other accolades, and her byline can be found in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Vogue, among other publications. Colored Television was named a New York Times Notable Book of 2024.

As Colored Television begins, Jane is living in the ambiguity of trying to publish a second book. Her debut novel was published to great acclaim, but she’s been working on her follow-up for 10 years. With a focus on “racial nomads,” the draft of the second novel is a sprawling and chaotic endeavor. Jane hopes that a sabbatical from teaching, that aligns with a family housesitting opportunity for wealthy friends, will prove to be the motivation she needs to finish the book, submit it to her editor, and grasp the golden ring awaiting her on the other side of publication.

Senna writes, “Jane hadn’t been about to miss out on the opportunity to pretend they were rich Black artists who lived in the hills. She had been determined to be that couple this year… This was the year she would finish the book she’d been writing for so long. She’d publish it and get tenure, and they’d be middle class and maybe even have the money to buy a house of their very own.”

Things do not go according to plan. Jane, looking for middle-class stability and security for her family, reflects, “Mulatto children of peripatetic artistic hippies did not want to age into being peripatetic mulatto adults with children. It was an endless loop. She wanted a real middle-class home the way only a half-caste child of seventies-era squalor wants a home.” Instead, she winds up destabilizing her husband and children, making herself miserable along the way.

Throughout the book, Jane lies—a lot—to her family, to her friends and other people in her life. While housesitting, Jane goes to great lengths to pretend to be wealthy, throwing an extravagant birthday party for one of her children and wearing the clothes of one of the homeowners. Senna describes this pretense by writing, “her mouth filled with the bitter taste of want.” But it is a very specific type of desire that Jane is trying to fulfill, one that is deeply connected to her childhood and her multiracial identity. The resulting bitterness and stress pervade her work and Jane’s editor eventually responds to her finished draft by opining that, “You’re doing yourself a disfavor by writing about race again—by writing about, you know, the whole mixed-race thing.” Inspired by a friend from her MFA program, Jane decides to make the jump to writing for television, where she endeavors to create “the Jackie Robinson of biracial comedies” for a streaming service. Adventures ensue.

In the end, Colored Television is a smart satire about the lengths someone will go to and the pitfalls of chasing success when the very idea of “making it” has been defined by society instead of oneself. As Senna writes, “Jane’s father had once told her that white people believed, deep in their hearts, that Black people would all choose to become white if they could. But Black people didn’t want to be white…. Black people wanted only a big yellow Victorian on the hill, not to be the white people who lived there.”

Colored Television will be discussed by the African American Authors Book Club on June 12 at The Center at Belvedere. All are welcome. Supplied photos.