Visitors to The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia are greeted by a tangle of painted trout suspended in a wash of green background, rising from floor to ceiling. The imagery invites them into the first-floor gallery, where they’ll find “O’ Powa O’ Meng: The Art and Legacy of Jody Folwell,” a career retrospective of the eponymous Pueblo potter. It’s an intimate yet comprehensive exhibition, covering 50 years of the life, work, and influence of a pioneering contemporary ceramic artist.

“O’ powa is ‘I came’—I came when I started making pottery. Life was really contorted for me during that period of time, and once I started working in pottery, it was like I came, I found myself,” Folwell says in the exhibition catalog. “And o’ meng is ‘I’m going forward’—I’m going to be focused. The Clay Spirit gave me the ability to move forward and become something or somebody that it wanted me to be.”

That “something or somebody” Folwell has become is a profoundly innovative and impactful artist and ambassador for Santa Clara Pueblo pottery, which is captured in the “Art and Legacy” aspect of the show’s title.

Featuring more than 20 clay works, the exhibition also includes texts, photographs, and a short video, all of which provide excellent entry and context into who Folwell is, the traditional cultural expressions she builds upon, and her influence on other artists in expanding the profile of Pueblo pottery, and by extension Native art in general.

One of the wall texts quotes the artist directly, giving audiences invaluable insight into Folwell’s character and spirit. “Many of my pieces have some kind of history behind them,” it reads. “Personal history mostly, and just the mere fact that I love living in Santa Clara on the reservation, it’s a fullness of life. It’s security. It’s a sense of belonging because my ancestors are here, and they went through life here. I was born here, I raised my family here, and I know I will die here, and this gives me a sense of myself and a connection to all of my ancestors and people in the future that will come from this place. That is so incredible.”

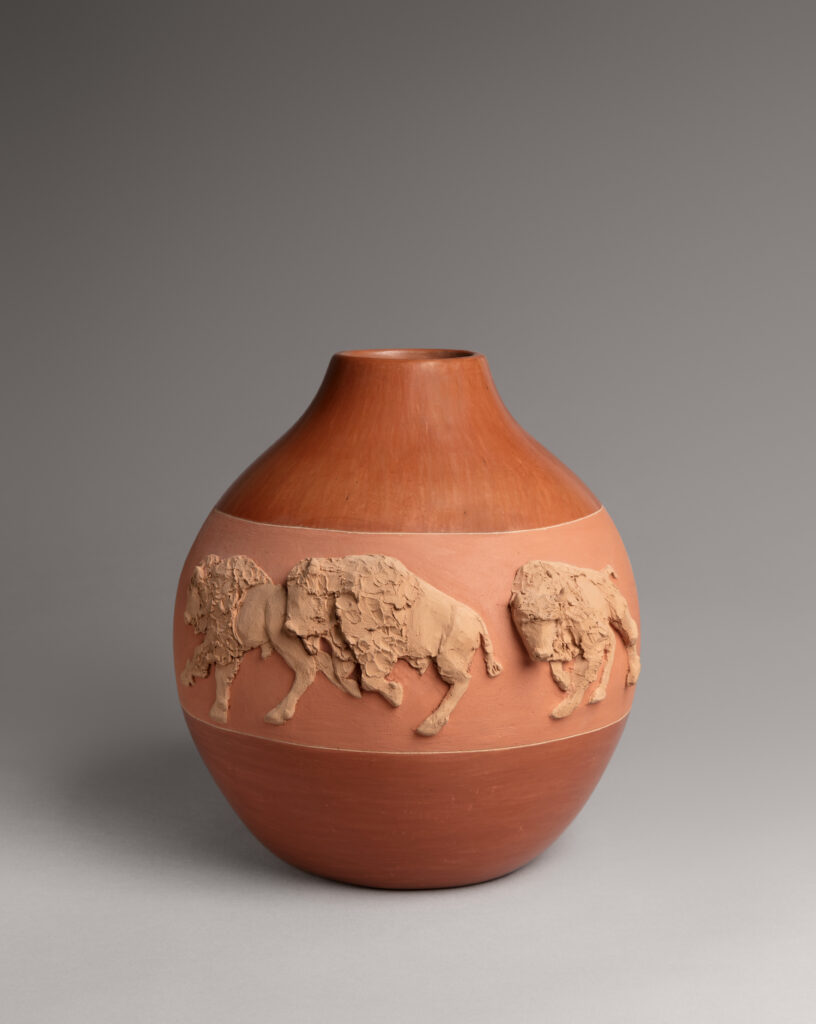

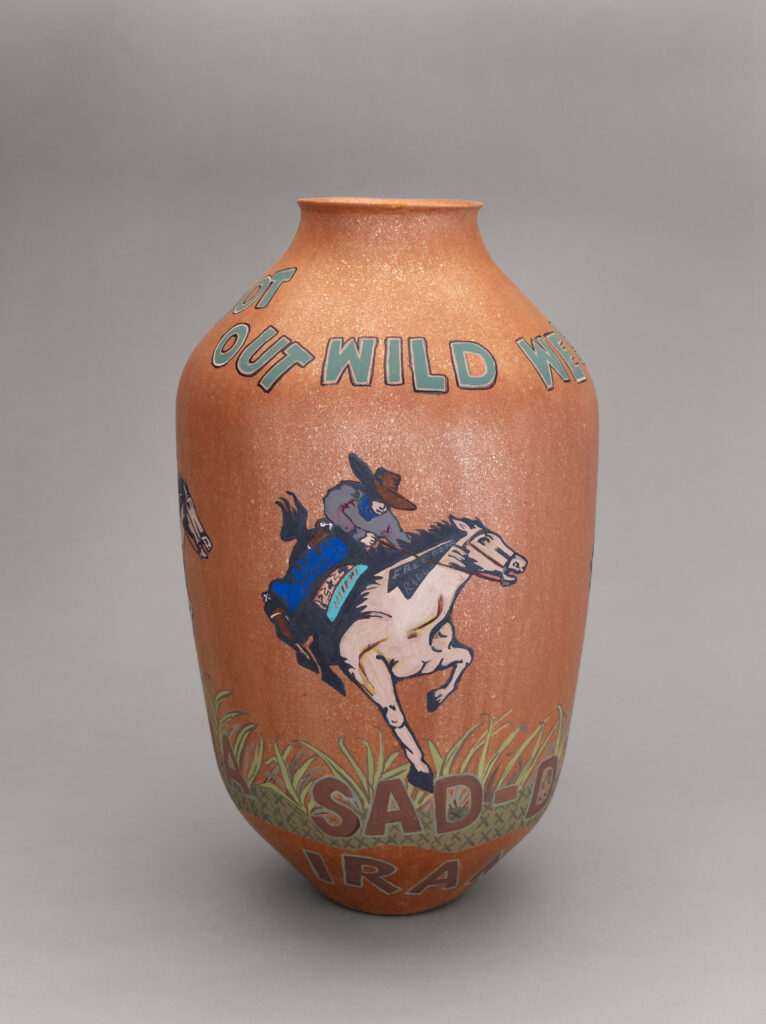

The majority of the works in “O’ Powa O’ Meng” are handbuilt vessels—pots, bowls, and urns. Many of the design elements used to adorn them are representations of fauna, including fish, frogs, horses, buffalo, dogs, and birds. Earthtones dominate the palette of the show, likewise reflecting a strong connection to the natural world embodied in Pueblo culture.

Extending beyond decorative motifs, Folwell’s designs carry strong narrative elements, communicating not only personal histories, but aspirational perspectives, homage, and political statements.

Designs painted onto or incised into the surfaces of the vessels exist in the round, alluding to cycles without beginning or end. This is particularly interesting within the more political works that offer narratives with representations of human forms. Works like “Wild West Show” and “You Don’t Push Bush” complicate our reading of linear time and history, calling into question historical records of events and their true points of genesis.

Some of Folwell’s most engaging works feature beautiful green hues, a radical innovation when she first employed the color in “The Hero Pot,” produced in collaboration with Bob Haozous and shown at the 1984 Santa Fe Indian Market. The work initially instigated dismissal by a number of the market’s judges, who debated whether the pot even constituted Pueblo pottery due to its form and color, and the fact that Folwell’s collaborator Haozous was not Pueblo.

Standing in stark contrast with the traditional red and black hues of Santa Clara Pueblo pottery, “The Hero Pot” ultimately won Best of Show. The judging panel decided it “represented innovation in an otherwise stale pottery marketplace,” says scholar Bruce Bernstein in the exhibition catalog. Taking cues from Folwell’s fresh perspective, and the change in parameters signaled by the judges’ high award, the innovative move prompted other Native artists to incorporate green hues and nontraditional applications of slip glazes in their submissions to the market the following year, effectively changing both collectors’ and potters’ definitions of what Pueblo pottery could be.

There is an incredible amount of variety in The Fralin exhibition. While most of the pieces are based on traditional Santa Clara Pueblo forms, Folwell has experimented with colors, slip glazes, design applications, and aspects of the forms themselves. Variations in the slope of a vessel’s neck, the rim around the opening, and exaggerations of certain compositional aspects of form may appear subtle, but they introduce enough visual difference to engage the viewer in seeking out similarities and departures within the show.

The exhibition design is a considered, measured installation that uses rich brown vinyl text on the walls, tying the didactic information to hues within the photos documenting Folwell’s pot-building practice, as well as to the physical works on view. This visual unity, enhanced by the tiled floor of the gallery, creates a cohesive and immersive experience. The voices of Folwell, her family members, and her collaborators emanating from a looping video, provide viewers with a sonic companion to the visual delights.

The woman behind the work

Jody Folwell lives and works in Kha’p’o Owingeh (The Place of the Singing Water), known to the outside world as Santa Clara Pueblo, one of six Tewa-speaking Indigenous villages located in northern New Mexico. Within these Pueblo communities, the ancestral and continuous pottery-making traditions stretch back as far as two millenia, if not farther.

Folwell was born and raised in the village, learning the traditional methods of handbuilding coiled-clay pots through a matriarchal lineage passed down by her great-grandmother and mother. She has experienced firsthand the expansion of Santa Clara Pueblo pottery from functional vessels used for food storage and preparation, to craft objects of cultural expressions sold to tourists and collectors as a means of sustaining the village and its community. Folwell has pushed that expansion further, facilitating breakthroughs for Native artists within the realm of contemporary fine arts.

Coming from a community of potters, Folwell sought a way to differentiate her works from those of her neighbors, artisans who were sometimes seen as more skilled practitioners of traditional Pueblo pottery. She began by taking what she called “half steps,” creating works based on ancestral forms with added, or altered, design elements. Her initial approach was both measured and considered.

“Most traditionalists, or traditional potters, do not expand or extend themselves out any farther than what they have been exposed to as children and as young adults, until they’re ready to retire, so that they remain within the confines of that particular thought in mind—it’s tradition, and that’s what it’s going to be,” Folwell says. “Because when you live in a very tight community, everything is looked upon by people around you—the community at large—to see what you’re doing. So when I first started out, I had to be extremely careful in not being able to expose what I was doing.”

While Folwell has continually pushed up against the boundaries of Santa Clara Pueblo pottery, everything she does comes from a place of understanding and reverence for the traditional methods and forms of her people, as well as the traditions and forms of other cultures.

“I still go back, and I have to always keep in mind that there are certain things that you have to keep learning in tradition,” Folwell says. “I don’t think that ever stops, but then once you start practicing that again, then you can go back, because it expands into something else that is the direction that you’re going to take.”

Inquisitive by nature, Folwell investigates and incorporates processes and aesthetics from Pueblo pottery in conjunction with creative expressions from Mexican, Japanese, and other Indigenous American cultures, among others, and is constantly experimenting with forms, firing and glazing techniques, and design elements.

“I’m 82, and the day that I leave this earth, I still would have to feel like I didn’t learn enough, I haven’t reached where I think that I should have reached,” Folwell says. “But maybe that wasn’t meant to be. It was maybe somebody else that will have to carry on that continuation from there.”

Expanding understanding

While she has been known and celebrated for years within circles that follow ceramic and Native arts, Folwell has not necessarily enjoyed the same recognition within the broader scope of contemporary art. A focused exhibition like “O’ Powa O’ Meng” highlights an individual artist, as opposed to an art form within a broader tradition.

“The importance of exhibitions such as these is to bring those two things together … correct that split that happens, whether intentionally or not,” says Adriana Greci Green, The Fralin’s curator of Indigenous arts of the Americas. “For Native art, we’ve got a tendency to focus on historic Native art, this idea that what comprises Native arts is things of the past, that really fulfill our preconceived notions of who Native people are. This kind of show, small as it is, is the opportunity to bridge those two divides and bring them together.”

This distinction between individual artists and the idea of what audiences expect to see in an exhibition of Native arts—

not just between individual artists or communities of people, but also across a span of time—is a facet that a show like this can define.

The term “contemporary art” often conjures expectations of abstract paintings and sculpture, or purposefully obtuse performance art pieces, reductionist views perpetuated by mainstream media depictions. These caricatures represent radically different expressions than the traditionally inspired Pueblo pottery forms adorned with narrative, figurative scenes as seen in “O’ Powa O’ Meng.”

“Jody is an exciting artist who’s been working for a long time, and bringing her work to a broader audience than the one that she’s been most exposed to—which has been more regional—is, I think, to the benefit of everyone,” Greci Green says.

A natural extension

Museum shows can take a long time to materialize. While exhibition planning for “O’ Powa O’ Meng” picked up steam in 2023, it was a concept that had been in motion for years, beginning with conversations between curators before moving into plans between institutions. As a co-presentation of The Fralin Museum and the Minneapolis Institute of Art, building the exhibition entailed input from numerous voices, with key contributions coming from co-curators Bernstein, senior scholar at the School for Advanced Research; The Fralin’s Greci Green; and Jill Ahlberg Yohe, an independent art curator and consultant.

“It took about two and a half years just to put the whole thing together in Minneapolis, and it was exhausting,” Folwell says. “I’m still processing it. I’m very delighted with it. I’m very excited about it.”

A beautiful through-line running between the process of planning the exhibition and the selected works on view is collaboration, with a nod to the legacy aspect of the show’s title. “O’ Powa O’ Meng” contains several collaborative works, whether between Folwell and fellow artists Haozous and Diego Romero, or by Folwell’s daughter and granddaughter Polly Rose Follwell and Kaa Folwell.

With the artist, we see this as a natural extension of her lived experience as a Pueblo and Santa Clara resident. When she was young, Folwell worked to help her great-grandmother make functional pottery for food storage and preparation. Later in life, she learned essential polishing techniques for her own pots from neighbors in her village.

Behind the scenes, collaboration is a necessity in mounting any exhibition, especially when drawing from a wide base of works to build a career-spanning retrospective. The works on view in “O’ powa O’ Meng” are meant to reflect the breadth and depth of Folwell’s extensive oeuvre.

“It’s a combination of our favorites, our knowledge, our research, and also Jody, things that she thought were particularly important that she wanted to see in the show,” Greci Green says.

Sharing in the creation process communicates that an idea is bigger than an individual opinion, creating additional impact by acknowledging the input of other voices, and consensus built on common ground.

Moments in time

Strong exhibitions give individual artists and artworks context, enabling audiences to confront their expectations and to have their view expanded. “O’ Powa O’ Meng” provides an excellent entry into the history of Santa Clara Pueblo pottery traditions, as well as Folwell’s personal history, creating an environment to better understand and appreciate the diverse works spanning five decades of creative expression and progression.

“I think the nice thing is that the public, the audiences, have had no problem being enthusiastic recipients of these exhibitions,” says Greci Green. “That kind of makes you think about all the opportunities missed in the past and all the opportunities that lie ahead of us in terms of when we do present contemporary art in this case, that American audiences are eager to hear more, learn more, open and eager to understand better the artistic output of all kinds of artists working today.”

Speaking more directly about this exhibition, Greci Green says, “Here really allows us the opportunity to focus on [Folwell] as an artist, and really on her as an artist in her own time, not just that she is a potter from a community of—a family of—pottery artists, but what she has to say as an American artist, in an American moment, or in a few moments across 50 years.”

That an exhibition dealing with a uniquely American experience would come to be presented in a time when the very concept of who and what are considered American is being questioned brings up an opportunity to recognize the experiences and perspectives of an individual artist whose work factors into this conversation so wholly.

For the artist, it’s an opportunity to not only look back, but to look ahead, as Folwell says, “Because as I had talked to Jill [Ahlberg Yohe] and Adriana [Greci Green], it has given me a new perspective on what I need to do, what direction to take, and the new work that I can accomplish.”

The reality of being a contemporary potter and continuing her work is innately tied to the phrase used by Folwell as the exhibition’s title, which she likens to the notion of a life’s path. “My path was set for me,” she says in the exhibition catalog. “Even now, I’m just halfway home. And when I’m sitting here looking back on it, then I’m saying to myself, ‘O’ powa o’ meng—I came here, I got here, I’m still going.’”

“O’ Powa O’ Meng: The Art and Legacy of Jody Folwell” remains on view at The Fralin through June 15, 2025. A panel discussion with artists Jody Folwell, Susan Folwell, and the exhibition curators will take place on Sunday, May 11, at Campbell Hall (School of Architecture) Room 153 at 2:30pm. A reception at The Fralin from 3:30–4:30pm will follow.

Photo: Eze Amos