A confession: I’m not adequately prepared to discuss Peter Allen’s “Un-becoming” show at McGuffey Art Center with the level of insight both the artist and his art deserve.

I certainly spent plenty of preparatory time and afforded the exhibition my contemplative attention. No, this is just a shortcoming of my own faculties—the same dearth that surely plagues the stupefied majority of Allen’s audiences. For there exists a gap of confounding distance between the viewer and the disarmingly tight collection of striking, illuminating, and unflinching personal visions alighting the walls of the Sarah B. Smith Gallery. For seven pieces, there is much to digest and decode.

I’ll liken my feeling of ineptitude to those moments when, reading an article, you pause to look up some referenced concept with which you’re unfamiliar; then, two minutes later, you find yourself on Wikipedia reading its definition for the fifth time, starting to question if it’s actually written in English, convinced that you know less after this fruitless endeavor than when you started, and cursing yourself for having dicked around so much during formative middle school math and science classes.

This is the overwhelming effect of Allen’s brilliance in visual art and poetry. To my great satisfaction, the artist’s statement and the ideas he’s shared about his creations demonstrate profound meaning. See, for a dummy like me, it’s a little intimidating.

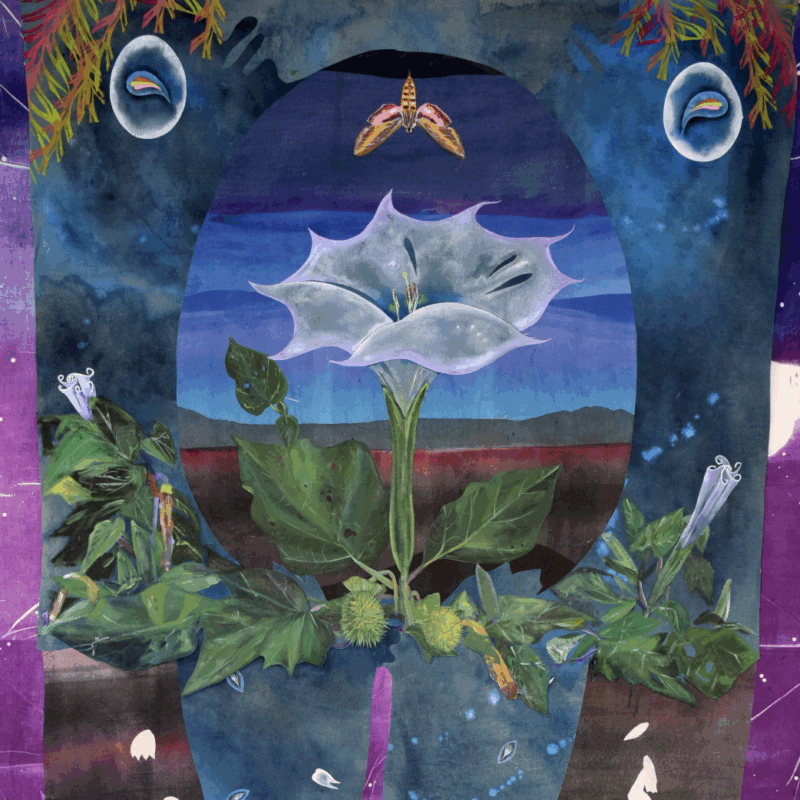

Allen, a McGuffey member since 2011, says that his penciled paper and canvas pieces contend with “the nature of the self and the pressures of context.” His autobiographical discoveries invite viewers to consider their own identities, too. This lofty impulse is advanced through an upcycling of public domain, commercial, and personal images, recontextualized in graphite. He then couples his visuals with hand-cut, stenciled letters on a grid, spelling out his poetry in vertical streaks without space between the lines, often mirroring itself in a backward orientation. Though difficult to read, Allen accurately notes that his texts, which harbor some likely unintentional resemblance to Gee Vaucher’s protest art for anarcho-punk band Crass, look “at once ancient and modern.”

These bi-media pieces require us to consider the meaning of the words, as well as the images. There is little doubt that a casual Friday night art crawl won’t suffice, nor will the half-buzzed gallery stroll-through that might otherwise do the job for art proffered without paired poems. This takes time. Muttering your knee-jerk Rorschach test appraisals to the person next to you won’t cut it here.

Check out the titles—even they demand explanation: “Sequela,” “Scotoma,” “Albedo,” “Anamorph.” The good news is that, for three dollars, you can get a chapbook of sorts, where conventional presentations of Allen’s poetry are served with definitions of the unfamiliar language he’s chosen for his works’ names. Honestly, his verse provides more shocking imagery than his visuals, ornamented with terrors like deformed spider parent domination, town-crushing giants from childhood, and a recurring theme of relatives performing mutilations on each other.

The sinister elements that arise in his penciled canvases are more muted: an arrogant bather tilting aggressively in the surf, the confrontational gaze of a man among a gaggle of unhappy children, a stunned Red Riding Hood scrutinizing a contented wolf dozing in her grandmother’s clothing.

The show’s first piece, “Sequela,” features a type of self-portrait bust bisected by a vertical stream of text; the subject wears an unsettling white paper mask with holes for the eyes, nose, and mouth. The mask itself hangs on the backside of the wall above the poem, “Vault.” The three-part text tells of wandering into a dense forest, referencing wolves and birds, animals that reappear in the aforementioned fable piece “Albedo,” and the perched bird of “Anamorph.” It’s an intricate pattern of meaning that no brief review has space enough to explore.

Viewers of Allen’s third solo McGuffey show will be taken by the explosive monochromatic beauty of “Zoetrope,” which extends across multiple panels, snaking around two walls. Allen says the idea for the work originated 40 years earlier, when as a college student, he would shoot photos on the train to New York for museum visits. It concerns his idea of time and space interacting as parts of the same illusion that obscures the viewers’ sense of location and ability to interpret what’s being observed. “Zoetrope”’s silhouettes, cloud bursts, rays of sunlight, windows, reflections, and waves of smoke make it impossible to tell.

Though Allen leaves us ample instructions for understanding his influences, ideas, and objectives, following him for the entire journey takes chutzpah. But, for those of us willing to take on the challenge, the rewards are many.