As Charlottesville continues to grapple with its long history of slavery and white supremacy, the city’s Historic Resources Committee is putting descendants of enslaved people at the forefront of the conversation. Since last year, the committee has met with around three dozen descendants, seeking their thoughts on how to best memorialize the thousands of people who were bought and sold in Court Square. Last February, local resident Richard Allan confessed to throwing the former slave auction marker into the James River, frustrated with the city for not erecting a better tribute.

Before continuing with the descendant engagement process, the committee sought guidance from architect Dr. Mabel O. Wilson during its October 8 meeting. For several years, the Columbia University professor engaged with students, staff, faculty, alumni, local residents, and descendants of enslaved people as she helped to design the University of Virginia’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, which was completed last spring.

When UVA put together the MEL design team in 2016, it did not have an exact budget, building site, or design in mind for the memorial. “That was a huge risk, but because it was open and wasn’t hemmed in by more conventional processes, it allowed for invention,” said Wilson.

To gather input from a wide range of university community members, the team hosted different types of public forums—including small groups, large conferences, and catered lunches and dinners—at easily accessible locations around town, like historically Black churches and the Jefferson School. They also sent out online surveys to ensure that people who did not live in Charlottesville had their voices heard.

“We were constantly negotiating and listening and understanding what it was that people wanted or expected,” said Wilson.

The team chose to build the memorial near—but not on—the UVA Lawn to help Black community members feel comfortable visiting it, explained Wilson.

“We were understanding as we started going along that folks in the Black community think of UVA as a plantation,” she said. “It’s still complicated.”

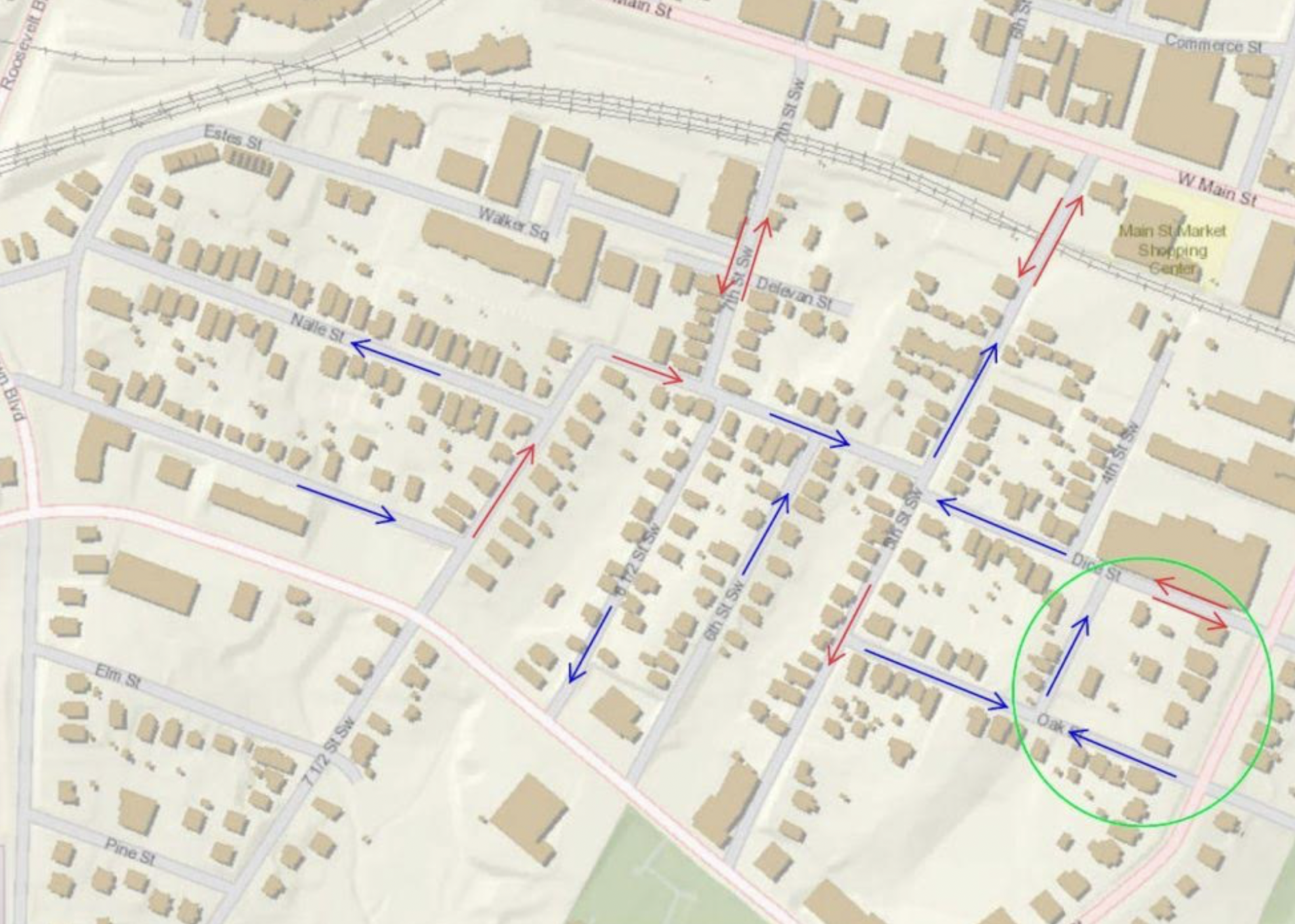

Pointing to the limited space available at Number Nothing, the former slave auction marker site, committee member Jalane Schmidt suggested the city look at additional locations associated with slavery, including Court Square Park, Albemarle County Circuit Court, Levy Opera House, and the former site of Swan Tavern.

Regardless of the memorial’s location, it must communicate the humanity of enslaved people, Wilson stressed. In addition to listing the known names of people enslaved at the university, the MEL includes those known by their occupation or kinship relation. It also features an excerpt from a writing by Isabella Gibbons, who was enslaved at the university and became an educator after emancipation, “speaking for the people who aren’t there,” she said.

“This is tough because it’s an auction block. It’s ground zero for that process of dehumanization,” said Wilson. “Given what this is marking, it might then call for other kinds of sites to be marked.”

Wilson strongly encouraged the committee to be open and patient as it brings a new memorial to fruition.

“Oftentimes, it’s a one and done. We’ve got that out the way—let’s move on,” she said. “But in Charlottesville, there’s a lot of ways in which the history of the city is being really rethought and leveraged to understand what’s not there, what’s not been said.”

“I think you guys are a model for how people can do this work.”