On a cold morning following a night with temperatures in the teens, Quincy Scott and Cheryl Burroughs are among the first to gather on the benches that line the Downtown Mall. Tents, sleeping bags, and blankets are pulled snug against the transit center to take advantage of an overhang that juts out slightly and keeps the snow off. Both are glad they didn’t spend the night there.

Scott overnighted at the Baptist church on University Avenue, and has been staying at church shelters since he was released from Central Virginia Regional Jail on December 14. He was there for a probation violation, but in the bigger picture, he’s returning from 15 years in prison. He’s staying in shelters while looking for a way to get back a piece of the life he left.

“I’ve got people rooting for me,” Scott says. “Friends, family, judges, everybody.”

Burroughs stayed overnight at Crescent Halls, a public housing facility on Monticello Avenue. She says she was taken there by police at 3am, following an altercation. Burroughs gives conflicting dates about where she’s been staying. For some time, she had an apartment at The Crossings, Charlottesville’s supportive housing community for those facing homelessness, but left. She says she’s been on the streets off and on for 15 years with chronic drug addiction.

Overnight shelters in Charlottesville are just that, for night use only. Scott has a bed through PACEM (People and Congregations Engaged in Ministry), but at 7 every morning he has to leave.

People can find themselves without shelter for a variety of reasons. Many, like Scott, are going through reentry after a period of incarceration. In 2023, about 30 percent of people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. reported having a serious mental illness with 24 percent being related to chronic substance abuse, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Approximately 10.4 percent of shelter services in 2023 were used by survivors of domestic abuse and their families, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

But experts on the topic agree that in Charlottesville, as well as in the nation, the single biggest issue causing homelessness is the lack of affordable housing.

In its three-year plan to end homelessness, the Blue Ridge Area Coalition for the Homeless reports that the greatest barriers in the area are lack of affordable housing, limited economic opportunity, and few supportive services for mental health and substance abuse.

“I think the causes here are the causes everywhere,” says Michele Claibourn, who works in data science at the University of Virginia’s Equity Center. Claibourn co-authored the 2023 Stepping Stones Report that measured factors related to community well-being for the City of Charlottesville. “Our population has increased, we don’t have enough housing, housing prices increase as a consequence, and people are priced out of rentals and certainly home ownership,” she says.

The United States Interagency Council on Homelessness estimates that 40 to 60 percent of people experiencing homelessness do have a job, sometimes two, but housing remains unaffordable. A full-time worker would need to earn an hourly wage of $26.94 on average to afford a two-bedroom rental in Charlottesville, according to a 2023 report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition. In only 7 percent of counties in the nation can a full-time minimum-wage worker afford a one-bedroom rental, the report says.

Affordable here means being able to pay rent without spending more than 30 percent of income on housing. Still, the wage needed to live in Charlottesville is almost four times the federal minimum wage, which means that households earning less than that could easily lose their housing if something unforeseen happened, such as a car accident, medical emergency, theft, or job loss. Households that spend more than 30 percent of their total income on housing are considered cost-burdened households, and in Charlottesville, about 50 percent of all households fall into that category.

Looking at the numbers

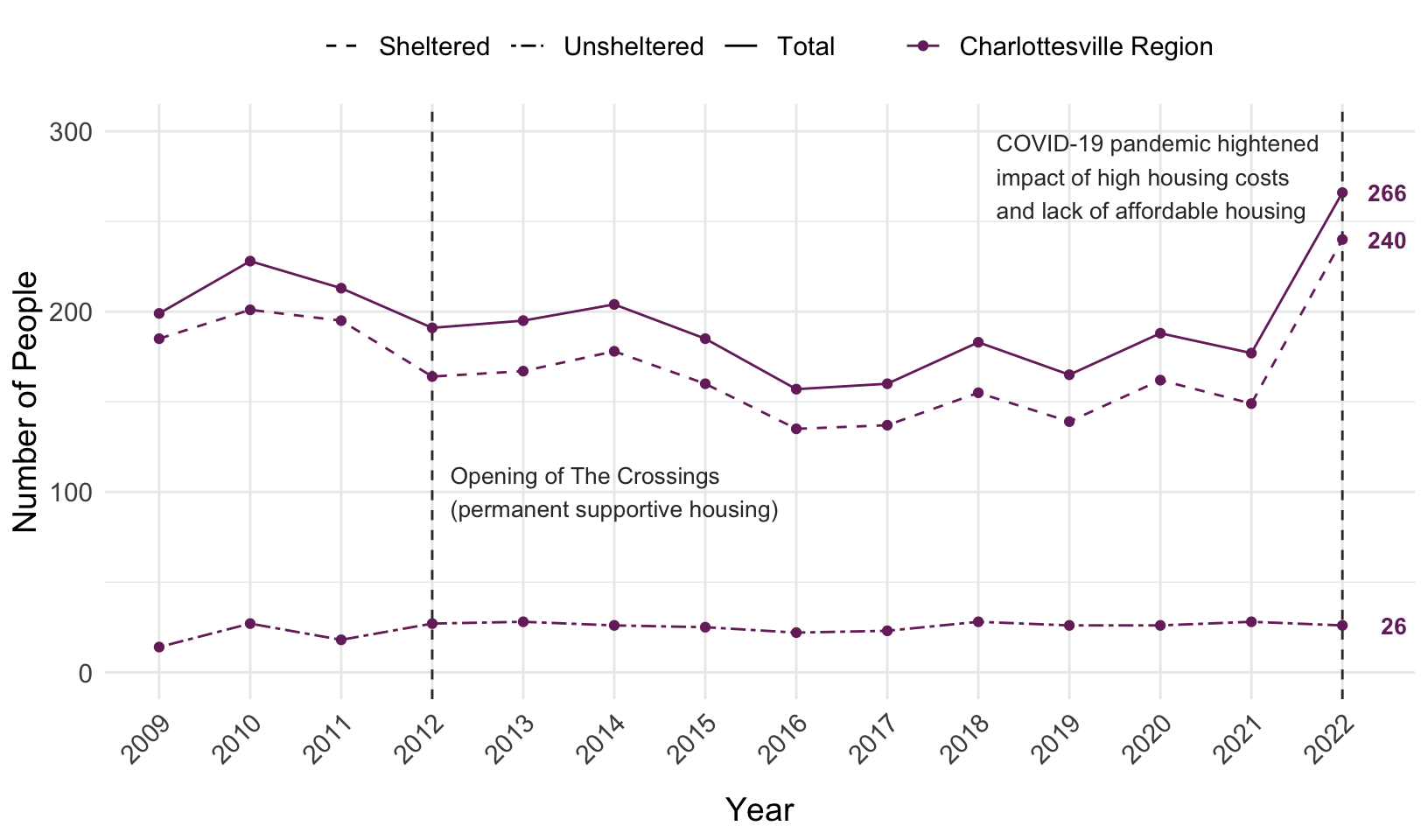

In 2022, the number of people experiencing homelessness in the area reached its highest point in the past 12 years at 266, according to the Point-In-Time count for that year. The area includes the City of Charlottesville and the counties of Albemarle, Fluvanna, Greene, Louisa, and Nelson. However, that number on its own can be deceiving. The PIT count spiked in 2022, from 171 in 2021. In 2023, the count returned to about the same level, at 191.

According to Claibourn, the spike is related to COVID-19 relief funds. One of the limitations of getting data about unhoused populations is that many people go uncounted if they haven’t interacted with a service agency. Claibourn says that in 2022 there was more money for shelter services, so more people sought services and more people could be counted.

That high point is not indicative of a rising trend in people experiencing homelessness, Claibourn says. In fact, the trend in homelessness has gone down overall since 2010, when the PIT count was 228. Another thing the numbers show is that the vast majority of people who enter a period of homelessness are able to exit homelessness if they’re given sufficient resources. Anna Mendez, executive director of The Haven, Charlottesville’s downtown day shelter, says for most people who experience homelessness, it’s a period of a few months.

“Because of our data collection, we know that in any 12-month period of time, between 400 and 500 people in our community experience homelessness,” Mendez says. “So, what that means is that they have either slept outside or they have slept in a structure not fit for human habitation, like they’re sleeping in their car. Or they’ve slept in a shelter, because people who are merely sheltered are still people who are homeless.”

The PIT count, which counts the number of people experiencing homelessness on a single day, is much lower than that. That’s because the vast majority of people who enter a period of homelessness leave it within a year.

The PIT count also tracks the number of people experiencing chronic homelessness, which is defined as experiencing homelessness for at least a year or repeatedly over the years. In Charlottesville, that’s about a quarter of the overall count, numbering 53 in 2023.

Claibourn says the numbers show us that homelessness is a solvable issue.

“It’s not such a huge number that you couldn’t imagine actually housing all of those people,” she says. “We’re not talking 10,000, we’re talking 150, right. The problem is there has not been enough political will to do so.”

The Haven

Both Scott and Burroughs start their day at The Haven, along with many others. The cafeteria, lounge, and lobby that comprise Charlottesville’s only daytime shelter is crowded and busy, especially on cold days. Because The Haven serves breakfast, it’s where the day begins for many of those seeking shelter.

People can also go to The Haven to take a shower, do laundry, store personal belongings, pick up their mail, and be safe. The day shelter distributes shoes, clothes, and other supplies that people have donated. It’s open every day year-round and is low-barrier.

“Low-barrier means that we do our best to welcome anyone who walks through the doors,” says Mendez. The rules are that guests can’t possess or use substances and can’t cause conflict. But people who are inebriated or under the influence or have a violent past are welcome to find rest at The Haven.

The shelter also functions as a kind of base camp where people can connect to the constellation of services available in Charlottesville, from housing to counseling. The Haven’s own housing department administers three programs that help over 200 households every year either exit homelessness or prevent them from experiencing homelessness in the first place, Mendez says.

Often, that work is preventative. If someone has an emergency and misses a month of rent, The Haven can help them. Or, if someone is facing an eviction that would result in homelessness, The Haven can help rehouse them.

“We really see a vision of Charlottesville where we are working toward eliminating homelessness,” Mendez says.

However, The Haven isn’t somewhere people can stay the night. The doors open at 7am and close at 5pm on weekdays and noon on weekends. After that, those seeking shelter have to find it elsewhere.

The Salvation Army

The Salvation Army on Ridge Street provides overnight beds, with 28 for men and 28 for women, plus a lobby with floor space for six men and six women in an emergency. But the Salvation Army employs a more structured approach than The Haven. Those seeking a bed have to go through an intake process and agree to the rules. The shelter opens at 4pm, with a break for dinner from 5 to 6pm.

“They are searched every time they go out the front door and come back in,” says Sandy Chirico, the Salvation Army’s social services manager. “So we look through their backpacks, turn their pockets inside out, and we do scan them with the metal scanner wand.”

The search is to keep out drugs, alcohol, and weapons. Guests also have to pass a drug test and breathalyzer. Curfew for the shelter is at 9pm. Breakfast the following morning is at 8am and people have to leave by 9am.

The Salvation Army has a case-management program for those staying at the shelter that is aimed at rehabilitation and, eventually, stable, independent housing. One of the key points of that program is securing employment, so during the day guests must either be working or looking for a job.

After intake, those seeking shelter can stay at the Salvation Army for 21 days. If they are meeting the goals of the program, the stay can be extended. Many stay up to six months, if they stick with the program.

Finding employment comes with a number of barriers for those living on the streets. The Salvation Army helps with filling out applications, following up with employers, having access to computers, providing vouchers for clothing, and many of the little things that can become larger hurdles if you’re in a tough spot. However, employment alone often isn’t enough to get out of a period of homelessness.

“Right now, I would say 75 percent of our folks are working,” Chirico says. “I don’t think the public is aware of that. Some of them are maybe lower paying jobs. It’s hard to live in Charlottesville on $16 an hour, $17 an hour.”

If securing employment isn’t enough, Chirico says case workers can help people navigate social services, get vouchers to the Salvation Army thrift store, and, in many cases, get a second job.

The Salvation Army is the only year-round, overnight shelter in Charlottesville, but the capacity is quite limited. In the winter especially, the need for shelter is much greater.

PACEM

During the coldest parts of the year, generally from October to April, some local churches band together to provide overnight shelter where they have space. PACEM is a coalition that pulls together 80 different congregations and community groups to provide shelter, so the shelter moves from one location to another every two weeks. Officially, PACEM has a capacity for 35 men and 15 women, but it will find shelter for anyone who comes to the door.

On a night in January, PACEM had set up cots for 44 men in the basement of University Baptist Church, and provided hotel vouchers for 11 more.

In the organization’s 20 years, “we have never had to turn anyone away specifically for capacity issues,” says Liz Yohn, PACEM’s operations manager. “Even when we are full, we make room.”

This winter, PACEM has seen more demand for shelter than expected. Yohn says the loss of supports that were in place for COVID has led to the increase.

“It supported so much,” she says. “It supported shelters and it supported individuals from ending up in homelessness. From things like additional food stamps and the unemployment insurance benefits to the eviction moratoriums, there were a lot of supports in place during the pandemic that aren’t in place anymore.”

PACEM doesn’t turn people away, but it does have limitations. The shelter is open from 5pm to 7am, and only operates for half the year. Because of its rotating schedule, the shelter can be hard to access, though for the more remote locations PACEM offers a shuttle that leaves from The Haven at 5:15pm.

PACEM is an emergency shelter for those who need it, but transitioning out of homelessness is a longer journey.

“We are the last rung on the safety net,” Yohn says. “In order to end up experiencing homelessness, there’s a lot of loss that you’ve probably experienced. It could be the breakdown of family and friend relationships, it could be mental or physical health that you’re struggling with.”

Shelter in Charlottesville is a patchwork of overnight, daytime, and seasonal options. Without a 24/7 emergency shelter, it can be hard to hold it all together.

Yohn says it’s been a challenge to find space for everyone who needs it, but the group has always found a way. That said, the official overnight capacity in Charlottesville doesn’t come close to the demand, as shown by the PIT count. There are many people who never come to PACEM’s door. In January of 2022, in the heart of winter, Charlottesville’s PIT count found 26 people sleeping outside of any kind of shelter.

On the Downtown Mall

Roscoe Boxley remembers working on renovations to The Haven before it opened in 2010. He recalls painting the ceiling and floors and touching up the exterior. By 2019, Boxley was coming home from prison, and work became harder to find. In 2023, he returned to The Haven, this time seeking shelter.

Boxley says he had to leave an unhealthy relationship and that included leaving his home. “I had to get myself in a better place so that I could be more attentive to my child,” he says. “So, I ended up just leaving everything altogether to reestablish myself and start over.”

At the time, Boxley was working two jobs, earning $10 an hour at Taco Bell and $11 an hour at Burger King. But child support and garnished wages meant he couldn’t afford a place of his own. He says he met people on the street from every background imaginable.

“People that are unhoused are not what people who aren’t unhoused think,” Boxley says. “There are a lot of people with skills, a lot of people with intellect, a lot of people that can solve issues that we have as a society. But most people who look at homeless people look at them all as if they’re the same, people who decided to make bad decisions or decided to disregard the law, or things like that.”

The issue of homelessness has been one of particular contention on the Downtown Mall. Boxley says there are efforts to force the unhoused out of the area.

“There used to be benches on the Downtown Mall,” Boxley says. “There were benches and stuff all around, but because homeless people laid on them, they took them up. Then they locked the power outlets, so you’re not allowed to plug your phones and stuff up. And they put these spikes along the windows of the bank where the heat exhaust is so that homeless people wouldn’t sit there. In the winter it’s the only place that blows heat, so you’ll see homeless people kind of gather right there.”

Boxley had put his own work into the downtown area. Years ago, he helped build some of it. But now, it was a place where he was unwelcome. Boxley says police were regularly called to enforce the 11pm curfew at Market Street Park to prevent people from sleeping there.

“Before COVID, a lot of these people were holding this society up,” Boxley says. “And now, because they’re homeless, people just want to get them out of the way.”

Frustrated, Boxley refused to leave the park. He set up a chair, held a sign, and wouldn’t go. It was a one-man protest. He was arrested and charged with trespassing and violating probation.

“My sign,” he says, “said ‘Make Room For Homeless People.’”

Tents in the park

A September 16 incident in which a police officer was accused of kicking an unhoused man sleeping in Market Street Park, and public outcry at a September 18 City Council meeting, led City Manger Sam Sanders to lift the park’s 11pm curfew.

Boxley estimates that 60 to 70 people were staying in the park. What sprang up was a refuge, but it was also a community where people who needed support were able to support one another.

“One, it was easier to access the resources that we needed, that was the most important thing,” Boxley says. “Then, to be close to each other, community-wise, it was about having a support system.”

But friction between the housed and unhoused population only became more evident. Boxley heard complaints that the homeless people in the park were dangerous, that the residents felt unsafe. There was also hostility.

“People throwing rocks or fruit, yelling ‘Get out of my damn park,’” Boxley says. “You know how many fights I got in over that park?”

The calls to remove people from the park grew proportionately with the calls of support. On October 21, those calls were heard. The curfew was reinstated, and by 11pm all the tents were gone.

Reflecting on the episode, Mendez says, “For us at The Haven, what saddens us most, is that at times it seems like people are more upset about having to see people who are experiencing homelessness than they are about the fact that in a community as wealthy as ours, the experience of homelessness still exists.”

Permanent supportive housing

The ultimate goal of the network of services and nonprofits in Charlottesville is to end the experience of homelessness in the community.

For Jessica Moody, the programs worked.

Moody was 47 when she lost her job at a customer service call center. In the beginning, she moved in with her daughter in Buckingham, but eventually had to leave because of limited space and the commute to her new job in Charlottesville.

“So I ended up being homeless in Charlottesville, working in hotels,” Moody says. “I was working in hotels, so I was staying in the hotels at night.” Moody bounced around between her car and hotel rooms.

“I’d worked hotels before and I know how they work,” she says. “A lot of hotels, if you work for them, they’ll give you a discount on a room or they’ll give you a room, you know, they’ll work with you. That’s why I came to work in the hotels here.”

Moody also worked weekends at a domestic violence shelter where she was expected to stay overnight. No one there knew she was homeless.

That went on for over a year before Moody sought help. She was referred to The Haven and, through The Haven, found PACEM. There, she was able to get a room for a year at PACEM’s now-defunct emergency shelter, Premier Circle.

Though Premier Circle closed due to funding last spring, the program highlighted how effective stable shelter and long-term support can be in successfully helping someone get rehoused. The future of the property, which was formerly the Red Carpet Inn, will serve a similar purpose. A renovation project, spearheaded by Virginia Supportive Housing, aims to build 80 permanent supportive housing units where Premier Circle once stood.

Shayla Washington, executive director of the Blue Ridge Area Coalition for the Homeless says that is the best tool for addressing homelessness.

“The most effective thing is permanent supportive housing. That comes with case management, it comes with rental assistance, and really just providing that strong case management piece that folks really benefit from.”

Like Premier Circle, permanent supportive housing offers a long-term room. Many, such as Moody, find the most value in the personal support and case management they receive at the facility.

“It’s great to have a good case manager, people who care,” Moody says. “That was very important to me. That’s what helped me.”

Typically, there are a series of losses that come before the loss of housing—loss of relationships, loss of jobs, loss of health. Resolving those issues is complex.

“We believe in a housing-first model, that you’re not going to address any other aims in your life until you have a stable house,” says Julie Anderson, director of real estate development at Virginia Supportive Housing.

Virginia Supportive Housing, which has operated at The Crossings since 2012, has 60 units available to those experiencing homelessness. The facility will add another 80 units by the spring of 2025, more than doubling Charlottesville’s capacity.

“The development will be 77 studio apartments, full studios with a kitchen and bathroom and living/sleeping area, as well as three one-bedroom apartments, and onsite supportive services, all for homeless or low-income individuals,” Anderson says.

The room isn’t free, but the cost is sliding to meet each person’s means.

“Residents sign leases and their rent is based on their income. They pay a monthly rent equivalent to 30 percent of their income,” Anderson says. “On average, our residents pay $200 a month. However, if you have zero income, the rent is just $50 a month and our services staff onsite can help the individual be connected with a church or somebody that will help them pay that rent every month if they need that help.”

That same system is what allowed Moody to finally find her own place last summer. Her case manager helped her get a voucher from the Charlottesville Housing Authority, which allows her to pay 30 percent of her income in rent. After a lot of searching, she found a room at Mallside Apartments.

“I’m in a place now and I’m so happy. I love it,” Moody says. “My apartment is nice. It’s small but it’s nice. I love the area. I’m happy to be in my own space.”