One early morning this spring, I walked through the door at Labor Ready, a day laborer employment service on W. Main Street, and took my place among the 30 or so people who had congregated at 5:30am looking for work.

People needing work congregate outside the Charlottesville office of Labor Ready, a national day laborer employment service that also has locations in Canada and the United Kingdom. “We’re just trying to help people get back on their feet,” says a local manager. |

There were all ages and types in there. The youngest looked to be about 20 while the oldest had to be around 60. Some of the men were tired, but others alive, joking and moving around, jostling with the early morning staff that decides whether or not to send them out to work, where to send them, and how they will get there.

“We’re just trying to help people get back on their feet,” said Alvin Jackson, the customer service representative of the local branch of the company that supplies approximately 600,000 temporary employees to jobs in construction, manufacturing, hospitality services, landscaping, warehousing, retail and more across the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

Later that day, I joined four others on a construction site on the south side of town. In our yellow hard hats and boots we stood amongst a pile of rubble, mostly planks and metal pipes, as a forklift operator picked them up and took the random items over behind a trailer where they were dumped. We stacked the wood on the forklift and moved Porta-potties so the machine could scoop them up and drop them in a less conspicuous spot.

By noon I was beat. The sun baked my neck and arms and my granddad’s old work boots only exacerbated the ache in my knees and feet. After lunch, I asked the forklift operator if they use Labor Ready much. “Yeah, but there’s so much turnover,” he said. “One guy might just work one day so he can get enough money for crack.” His words were borne out by one of the Labor Ready workers, an older man who had to leave mid-morning to report to his drug treatment supervisor.

With a scraggly salt and pepper beard, the old crackhead appeared constantly irate and when another day laborer and I took a seat in a deserted hallway he approached menacingly, his voice at a decibel level way too high. “You can’t sit here,” he shouted at us. “The ‘supe’ don’t like it.” He glowered at us and pointed to an adjoining room and a pair of brooms we were supposed to use to sweep the floor. He seemed to save his fury for my companion, a tall, stringy African who studies chemical engineering at UVA and does Labor Ready for some extra cash. The old man yelled at him throughout the day.

While my peer swept I slipped out a side door and went to find the superintendent I’d been assigned to. By late afternoon I was digging dirt with a shovel and pouring it on the base of a makeshift retaining wall. The rest of the day laborers were inside the building cleaning out a dingy dusty room strewed with broken concrete and insulation. When I had finished excavating, the day was finally over…sort of.

Next was the wait. Many of the day laborers have no transportation and so someone from Labor Ready had to drop us off and then pick us back up. We were off at 4pm, but after an hour of waiting I called a friend for a ride. Shortly thereafter, Alvin Jackson showed up in an economy car and loaded up the three who had been telling horror stories about the times they had waited hours in the freezing cold for a ride. The African and I waited for my friend to come and rode back with her to Labor Ready where our checks were going to be processed. We were getting $7.50 an hour to be the butt of civilization.

Making ends meet

When I first started to work on this story I envisioned it as a report on what it’s like to be a member of the working poor, but an additional night working in a kitchen (until I gave out) convinced me that there was a better approach to writing about poverty than simply describing the horrors of working two and three jobs a week to make ends meet. The working poor are just one segment of an overall population that exists under the poverty line. So I decided to broaden my reach and take on the state of the poor in our area, period. That led me to Anne Friedlander, who runs the Holy Comforter Soup Kitchen out of the basement of the similarly named church located on E. Jefferson Street. Every Thursday at noon, she and a handful of elderly volunteers serve food to a packed room.

Holy Comforter Soup Kitchen operates out of the basement of the similarly named church on E. Jefferson Street. Every Thursday elderly volunteers serve food to as many people as the room can hold. |

To my surprise, it was good food and there was a lot of it. I grabbed a plate and took the heaping portions of some kind of ground beef and gravy poured over rice to one of the tables and took a seat next to a man in his 50s or 60s. A construction worker by day, he also waits tables at night on the UVA Corner, that is, when the students are in town. Now he is searching for more work merely to get by.

“When you add in the cost of an apartment, that’s $600 or $700 a month,” he explained in between mouthfuls. “And then with bills…” His voice trailed off. “But the worst is if you get injured,” he said, not altogether unlikely when working construction, especially if you’re 60 years old. “Then you lose your job and you can’t pay for anything,” he glumly stated, shook his head and swallowed another bite of food. “You might end up homeless,” which is what happened to him for eight months once. “It wasn’t that bad,” he said matter-of-factly.

Fortunately, as I found, there is a surprisingly broad network of support for the economically disadvantaged of Charlottesville. For instance, when a person runs into one of these medical emergencies, Holy Comforter has a kitty set aside for just such circumstances. They will pay for medication—provided they are shown an official prescription—or help out with medical bills. And in addition to the soup kitchen, Holy Comforter sponsors three food give-aways—called Food Pantries—a week. On Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday mornings, families and individuals can show up at 10am and receive bags of free food, courtesy of the Thomas Jefferson Area Food Bank by way of the USDA and food purchased by the church itself. A normal bag of food contains pasta, bread and canned vegetables, among the numerous items.

Holy Comforter is far from the only church to host a food giveaway. Down Fifth Street Extended, at Jackson-Via Elementary, is the Loaves & Fishes Food Pantry put on by First United Methodist Church that offers both USDA-provided food (supplied by the TJ Area Food Bank) and donated food from churches and other local organizations. Open Saturdays from 10am to 1pm and Tuesdays from 7pm to 9pm, their hours of service were designed with a two-fold purpose.

“We targeted times that would hopefully accommodate peoples’ work schedules,” says Jerry Denney, who runs the pantry. “A lot of the other food pantries are open from 10 to 12 during the day but that’s not always the best time for the working poor. Hopefully, we’re giving people an alternative time where they can get out to pick up some food.”

Establishing whether someone falls below the poverty line is not an exact science. “We target households making under $20,000 a year,” says Friedlander of what seems to be a general across-the-board mark. Not surprisingly, the federal government has set up its own standards when determining if someone is eligible to receive food under the USDA program. For instance, a single individual’s income must fall at or below $14,700 to receive federal sustenance (under guidelines that expired at the end of June), while a family of two must be at or under $19,800, and a family of four at or less than $30,000 a year meet USDA requirements. That’s where pantries like Loaves & Fishes come in. Half of the over 200,000 pounds of food they gave away in 2006 was supplied by the church itself. “If you come to us and need food you will always get pantry food,” Denney says. “There are a lot of people that just can’t make ends meet.”

Every day’s a work day

Many years ago, when I was a student at the University of Arkansas, Jesse Jackson came to speak. A few years removed from his 1988 presidential run, his speech was much like the one he gave at the Democratic Convention, a moving address aimed, perhaps imprudently, at the working class, by and large a group that doesn’t vote:

“What’s the fundamental challenge of our day? It is to end economic violence. Most poor people are not lazy. They’re not black. They’re not brown. They’re mostly white, and female and young. Most poor people are not on welfare.

I know they work. I’m a witness. They catch the early bus. They work every day. They raise other people’s children. They work every day. They clean the streets. They work every day. They change the beds you slept in in these hotels last night and can’t get a union contract. They work every day.

They work in hospitals. I know they do. They wipe the bodies of those who are sick with fever and pain. They empty their bedpans. They clean out their commode. No job is beneath them, and yet when they get sick, they cannot lie in the bed they made up every day. America, that is not right. We are a better nation than that. We are a better nation than that…”

Not much has changed since Jackson’s plea. In fact, it’s only gotten worse. Many of the working poor slave away not only every day, but all day. That’s where something like the establishment of a living wage would help immensely. Many of the working poor hold down two—even three jobs—taking parents away from their children and creating a street culture that is repeated over and over again.

Last February the Albemarle Board of Supervisors met to consider a proposal to raise the living wage for county employees to $9.75 or even $11.07 from the current $8.81 an hour. Despite the protests of supervisors Sally Thomas and David Slutzky, the Board rebuffed the proposed increases with Chair Ken Boyd providing a simple blunt epitaph. “I don’t see how we can fund this,” he said.

“I don’t know why the county is so comfortable shooting down the living wage,” says Slutzky, who led the charge to raise the wage. “I think it’s really shameful and it tells me that this Board—with the exception of Sally—doesn’t seem to have much compassion. It’s all about the money and they didn’t want to burden the taxpayers. They’d rather give a reduction in the tax rate for the people wealthy enough to own land.”

The Board seemed to cave to a local populace demanding a deduction in the real estate tax rate. “It was probably politically unpopular for me to vote and push for the living wage, but so what?” says Slutzky. “There’s a moral imperative and that’s our job. Sometimes we’re supposed to do things that aren’t popular because they’re the right thing to do and I think the Board really missed the boat on this.”

Twenty percent of the county currently lives below or at the poverty line. “That’s a disgraceful circumstance in a county that has as much affluence as ours does,” continues Slutzky. “That we can’t even pay our own employees enough to not be in poverty is just shocking to me. It really bothered me as a citizen and made me feel bad that the other Board members—other than Sally—clearly did not feel compassion for the economically disadvantaged.”

The reason the Board was even discussing the issue of a living wage was likely due to the pressure 17 UVA students brought on the University a year earlier when they enacted a “sit-in” to try and force the school to raise their employees’ minimum wage to $10.72 from $9.37. The students’ efforts failed but their resulting arrest gained tons of exposure for the issu

e.

Change could also come on the state level, if only we lived in a different state. Just north, Maryland recently took the step of becoming the first state to enact a living wage law requiring large private state contractors to pay their full-time employees $11.30 an hour in certain urban areas and $8.50 per hour in rural areas. Virginia went the other direction, refusing to even raise the minimum wage, which has been stuck at $5.15 since 1997. In February, the General Assembly rejected a bill that would have boosted the wage to $6.15 in 2008 and $7.25 by the end of 2009. Maryland, on the other hand, has adopted a higher minimum wage than the federal government mandates, which is what Virginia’s rate is tied to.

A Band-Aid

While UVA, Albemarle County and the Commonwealth have failed to come through, Charlottesville has responded to the needs of the economically challenged—25 percent of city residents live under the poverty line—by giving full-time city employees $11 an hour. They also recently pledged over $1 million to go towards affordable housing. Surely, some of the city’s overall approach is attributable to the presence of an advocate for the poor right on City Council. Elected in 2006, Dave Norris is also the executive director of PACEM (an acronym for People and Congregations Engaged in Ministry), a rotating shelter for the homeless hosted by a number of churches who give up space to house those without a roof over their heads during the cold months of November to March. Started in 2004, PACEM hosted 237 homeless people last winter with an average number of 47 a night.

City Councilman Dave Norris is also the executive director for People and Congregations Engaged in Ministry (PACEM), a shelter that hosted 237 homeless people last winter. |

Right now, Norris is busy fundraising for next winter. “We continue to provide year-round individual support for homeless people that need help trying to find a job, or trying to get an apartment, veteran’s benefits, food stamps, or whatever it is.” According to Norris, many of the homeless are mentally ill. “To me, it’s a real shame that in our society of such wealth that we allow people who are severely mentally disabled to try to fend for themselves,” he says.

“Shelters are not an answer, they are a Band-aid,” he says. “The answer is getting people into housing and getting them the services they need. The two big culprits are a lack of affordable housing—we’re talking about apartments that are $400 a month or the equivalent thereof—and lack of services or people not being able to access services.”

A vicious cycle

Among current candidates for president of the United States, John Edwards is running on an unusual platform: the so-called war on poverty—unusual because it is highly unlikely to stir voters. The poor don’t vote, older white people do, and the unfortunate are not their chief concern. John Edwards will almost certainly lose on that type of notion, but one Edwards who won’t is Holly Edwards. Nominated for a Democratic seat on the Charlottesville City Council on June 2 she will likely join Norris next year as an active advocate for the less fortunate.

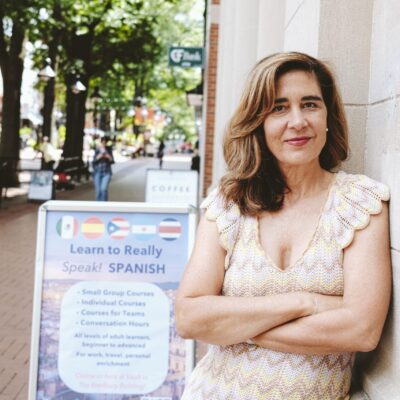

Holly Edwards has spent several years working at Westhaven Clinic, which looks out for those in the public housing sector. She says that there’s a “vicious cycle of people that are working but don’t have enough money to pay for more medical care.” |

One morning, I met Edwards at the Westhaven Clinic at 801 Hardy Dr. that sits at the corner of a public housing development. For the last five or six years, Edwards has worked at the clinic, first as a paid employee but now as a volunteer after an area hospital decided that funding a nurse at the community center was not one of their priorities. The clinic operates largely as a bridge, a reference point so that those in the public housing sector can seek out medical care there and elsewhere.

“Have you ever been here before?” she asked me, waving her hand across the humble apartment complexes surrounding the clinic. “Well,” I said, slightly embarrassed, “I used to live in the Starr Hill building, so I used to drive by here all the time, but that’s the extent of it.” Edwards looked at me a bit discerningly, I returned her gaze, mine a tad sheepish.

The truth is I was always a bit wary of the rundown neighborhood that was first formed in 1962 by the Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority as a $1.5 million housing project in an area then called Cox’s Row. Dubbed Westhaven, Charlottesville’s first public housing site was completed in 1964. The first of 126 families moved in on December 14, a Monday morning. Ever since, the rent to this day is based on the family’s income and the number of people in a family and varies from a minimum of $25 to a maximum of $90 per month.

It doesn’t look like it has changed much since its creation more than 40 years ago. Since I had never walked through, Edwards offered to give me a tour. Up the street we stopped in front of one of the small drab apartments to talk with a local activist named Joy Johnson, who Edwards laughingly referred to as a “loose cannon.” She lives in public housing.

Once Edwards tells her about my story, Johnson asks if I have heard about Albert, a 52-year-old man with a whole load of medical issues. Because the hospital’s financial screening process is so arduous he didn’t go through it, but in the meantime had a heart attack, which means the cost overall is going to be greater because he had no preventative care. “He’s part of the vicious cycle of people that are working but don’t have enough money to pay for more medical care,” says Edwards.

Just then a young woman and a male companion emerge from the apartment next to Johnson’s and as she walks past Edwards speaks up. “Are you working now?” she asks. “Yeah, Wendy’s,” answers the girl. “Good, good,” says Edwards as the girl walks away. “I had to ask.” Johnson, loose cannon that she is, jumps back in.

“What they [the hospital] don’t tell you is what they put you through to get the financial screening, and how little the screening is,” she laments. “I only make $10,000 a year because I only work part-time. And I’m a two tier. Well, what does that mean? I’m paying $60-70 a month for medicines.”

A former nurse at Martha Jefferson and a community activist for years, Edwards is more than familiar with the plights someone like Johnson faces. And as a burgeoning politician, she has already developed a certain kind of tact for stating the issues in a more sanitized fashion. “Clearly there’s a need to have more information about what the screening process entails,” she says, laughing again at Johnson’s bluntness, “how the tier process is defined, and put it in a way so that it will be meaningful for those going through the process.”

Johnson picks right back up. “I might be O.K. this month for my rent because I rob Peter to pay Paul,” she says. “So I paid the rent on time this month, but next month I’m getting my meds. So that makes my credit bad, but I can juggle. What about the people that don’t have the ability to juggle, they just fall behind.” Her empathy is more than palatable. “We’re living from paycheck to paycheck, and if you miss work, oh, God forbid, that’s another strike, because you know most people don’t have insurance.”

The ubiquitous Jesus Christ—inspiration for many of the local groups helping the poor—had much to say of their plight and displayed intolerance toward those that did not help. For instance, in the book of Matthew (Chapter 25, verse 45), he says, “Inasmuch as ye did it not to one of the least of these, ye did it not to me.” Or six chapters earlier, Matthew tells the story of when a rich man came to Jesus and asked what he could do to obtain eternal life. After a long list of requirements, Jesus replied: “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give it to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven.” According to Matthew, the man sulked away, “for he had great possessions.” At that point, Jesus turned to his disciples. “Verily I say unto you,” he said, “that a rich man shall hardly enter into the kingdom of heaven.”

One man trying to defy this notion is Tom Shadyac, the director of Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, Liar, Liar, and the new Evan Almighty. Last year, when he was in town to film portions of the latter film, Shadyac attended a living wage rally where he was motivated to act. After a discussion with Councilman Dave Norris, he decided to buy First Christian Church on W. Market Street for a reported $2.5 million to act as a resource center for the homeless and poor.

Living in this area while filming Evan Almighty, director Tom Shadyac, with beard, was inspired to buy First Christian Church on W. Market Street, which will serve as a resource center for the homeless and poor. He believes poverty here is “solveable as opposed to a place like L.A. where there’s tens of thousands of homeless.” |

“I feel blessed to be able to help,” Shadyac told me, standing in the middle of the empty sanctuary. Somewhere, Jesus is smiling. “I feel it’s important, whatever I’ve been given, to share that.”

“Tom has a real heart for the homeless,” says Norris.

“I have a burden for wherever there’s a need and there’s a need in this community,” says the director, a former UVA student. “Charlottesville not only felt like home because I went to college here, but the problem was very solvable as opposed to a place like L.A. where there’s tens of thousands of homeless.”

Once it is finished (projected to be next winter), the renovated old church will be a multipurpose facility, with the downstairs a homeless day shelter with showers and a soup kitchen. The top level of the facility will host groups that work with the homeless like PACEM and COMPASS that will run the shelter below and interact with the poor, from encouraging them to attend the Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings that will be held there to getting them job training. The main level of the church, the sanctuary with its high arches and beautiful stained glass, will be a shared community space for—according to Shadyac—theater, speakers, poetry readings, plays and music, both to enrich the lives of the poor and the broader community. “Then hopefully they’ll all work together helping one another,” the director says.

“Homelessness and poverty can only be eradicated, not through money and means, but through care and compassion,” Shadyac continues. “This is just a step.” Ultimately, the director hopes the center will inspire the surrounding populace to get more involved. “This is only going to work if the community embraces it,” he says. “I’m going to get it going and then the community has got to show an interest and a desire.”