In late April, three plainclothes federal agents swept into Albemarle County General District Court, and carried out some of the Trump administration’s earliest-known local courthouse detentions.

There, in front of stunned witnesses, agents detained Teodoro Dominguez-Rodriguez and Pablo Aparicio-Marcelino, who had each appeared in court while facing separate criminal charges. The sudden arrests—and the failed attempts of two bystanders to intervene—ignited outrage, fueling debate over the administration’s aggressive tactics and the use of courthouses, once considered off-limits, as hunting grounds for immigration enforcement.

Dominguez-Rodriguez’s detainment by the three men (one wearing a balaclava) was documented in a video obtained by The Daily Progress. After being handcuffed, Dominguez-Rodriguez was marched out of the courthouse by the agents, and driven away in a blue Ford.

Both Dominguez-Rodriguez and Aparicio-Marcelino were held at the Farmville Detention Center, where Kilmar Abrego Garcia currently remains. According to state records, they later appeared in local court, but neither is currently in ICE custody per the organization’s website.

In an interview with C-VILLE, a Legal Aid Justice Center attorney who’s involved in the case revealed Dominguez-Rodriguez voluntarily left the country after his public detainment.

Dominguez-Rodriguez’s story is an example of the Trump administration’s immigration policy in practice: Increase mandatory detentions to pressure voluntary exits, regardless of the merit of cases, and deliberately create confusion via rapid changes to policy and court proceedings.

Anyone with an address

Since inauguration day, groups already vulnerable to detention and deportation—namely anyone facing criminal charges—continue to be targeted by ICE. However, to meet the sky-high 3,000 daily arrest quota, the Department of Homeland Security and ICE have stretched the definition of what warrants detention from potential public safety threats to seemingly anyone with a known location.

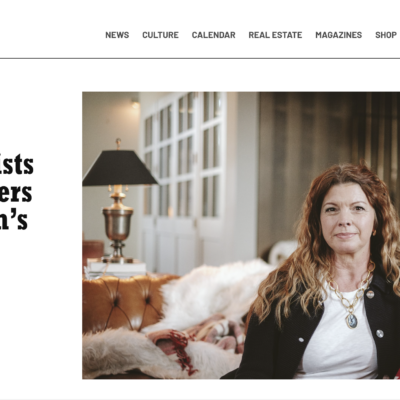

“Targeting people at workplaces … people [who] have criminal records … that’s been a constant. That’s not new, but the definition of criminal record has definitely expanded under this administration,” says Kristin Clarens, an immigration lawyer with the LAJC.

Local immigration experts like Clarens have received reports of minor charges, including speeding tickets for 15 miles per hour over the speed limit, leading to detainment.

For those without a criminal record, participating in immigration proceedings now also comes with the risk of detention.

“People who have already made themselves known in some way, or … entered the country legally and are in proceedings, or have sought some sort of immigration relief, ICE and USCIS [U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services], they know what their address is. They know where they are. They know all their information,” says Sophia Gregg, senior immigrants’ rights attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia. “They are the low-hanging fruit for ICE to ultimately fulfill their quotas.”

Fast-track deportation

One change contributing to the spike in immigration detentions, and the denial of immigration parole, is the expanded criteria for expedited removal.

As the term implies, expedited removal allows the U.S. government to rapidly deport someone with minimal court proceedings and limited rights.

“Expedited removal historically has only been applied to people who enter the country … without inspection—so people who enter not through a port of entry, but enter by other means into the country, not legally—and are caught very close to the border,” says Gregg. In other words, what once applied only to people caught sneaking across the border can now be used for someone pulled over for speeding.

From 2004 to 2020, expedited removal proceedings were only applicable to migrants at a port of entry, those who entered by sea, or anyone located within 100 miles of a U.S. border within two weeks of their arrival.

“The government interprets expedited removal to indicate that these people are not entitled to a hearing on their underlying reasons for staying in this country,” says Clarens. “It’s harder for them to assert an interest or a fear of return to their home country within the time frame of the process that’s being … applied against them.”

“There are fewer protections in place [with expedited removal]; it’s just a process that can move much faster. … They could be gone by the time we hear from their families,” she says.

The U.S. government is now pursuing expedited removal of anyone undocumented, or with a vulnerability in immigration status, who

cannot prove United States residency for at

least two years. Anyone facing expedited removal is ineligible for parole and must remain in detention.

In detention

It’s technically not prison, but conditions in immigration detention are strikingly similar to incarceration. Between the Farmville and Caroline County detention centers, Virginia has a 1,000-bed capacity for immigration detention.

“There’s barbed-wire fences, there’s locks on the doors, their [detainees’] movements are restricted,” says Gregg. “While Virginia has two major detention centers, those detention centers are at or exceeding capacity limits. There’s real concerns of conditions within those facilities, given that increase in the populations there, whether or not they’re getting access to adequate services and care while they’re in these detention centers.”

The exact reason he was deemed ineligible for parole is unknown, but Dominguez-Rodriguez is part of a growing population that has opted to voluntarily leave the United States rather than continue their immigration case from detention.

“He was going to need to fight his underlying immigration case … he would have been detained the entire time,” says Clarens. “It’s not unusual for proceedings to take many years and it’s unclear how much more quickly things are moving for people who are detained.”

“Lots of people in that similar situation … who are starting from the beginning of their immigration case have just decided it’s not worth it [to] stay in a detention center,” she says. “It’s not a great vibe.”

In addition to conditions in detention centers, potential third country removals have prompted some migrants to leave the United States, forgoing their due process rights. The already complex process of obtaining legal representation, or representing oneself, is further complicated in custody. Unlike the criminal system, defendants are only entitled to an attorney if they can obtain one.

Pro-bono immigration lawyers are in short supply in Virginia. The cost of obtaining a private attorney can range from thousands to tens of thousands of dollars depending on the complexity and location of the case.

“In many instances, people are unable to get immigration attorneys,” says Gregg. “Statistically speaking, people are much less likely to be able to win an immigration case without an attorney.”

Once someone in detention has obtained representation, through a pro-bono lawyer or paid attorney, getting out on immigration bond is a top priority—and expense.

Detainees must post the entirety of their bond—usually $5,000—to leave custody.

“The goal when I get a new detained client is always to try and see if there’s a way of getting them out of the detained track,” says Charlottesville-based immigration attorney Tanishka Cruz. “You have access to your job, you’re able to pay for the representation, you’re able to collect evidence. You’re just able to do more, and you’re way more limited in a detained environment.”

Feeling the impact

From civil rights watchdogs to activist organizations and local attorneys, everyone in immigration law has felt the impacts of Trump administration policies and ICE activity.

Despite a foreign-born population of 13.3 percent (a full percentage point below the national average), Virginia has experienced the largest increase in immigration enforcement under the Trump administration, reports the ACLU. A July article from The New York Times corroborates this, with data showing ICE arrests in the commonwealth up more than 350 percent from last year.

“[The LAJC is] seeing a steady stream of referrals to our intake system for detained people looking for legal assistance,” says Clarens. “We’ve seen an increase in Charlottesville, but … we’ve seen a really high increase in northern Virginia.”

In her practice with LAJC, Clarens works on a range of immigration cases, including asylum, humanitarian parole, U-visas, and T-visas. Immigrants in proceedings to affirm their legal status have also encountered challenges from nationwide policy and enforcement changes, which have led to devastating consequences for some.

“Somebody comes in and [asks] me for help with something, and then a week and a half later they get a speeding ticket of 15 over which … [could] derail their ability to file for a green card, which would allow them to evacuate their family from Afghanistan more readily. That time frame of that speeding ticket then bumps up against the implementation of the travel ban, and then the person will never be able to see their family,” Clarens says. “I really wish that that was emphasized more. I think most people think that they’re going after … these violent gang leaders. In fact, anybody who has any sort of mild infraction, [and] is trying to change their immigration status, is vulnerable.”

No matter the kind of immigration case, local attorneys and activists alike say the most disruptive shift has been the ever-changing and seemingly unexplainable alterations to court proceedings.

“I’ve always been busy. That’s never been the issue. The problem is the chaos,” says Cruz. “We’re just further exasperating a system that needs to be reformed, that needs overhaul, that needs correcting. There’s no solutions being put forward. We’re just breaking things further, from my perspective, and … there’s a lot of people being hurt and caught in the crossfire.”

Court chaos

Failing to appear for immigration court hearings can have severe consequences, up to and including detention and deportation. Now, court proceedings and ICE check-in times and locations are being moved around and scheduled at atypical hours—with limited notice or reason.

“Immigration court hearings are being scheduled and changed faster or in sort of a weird cadence, and that’s really scary, because if you miss an immigration court hearing, you get a deportation order because you didn’t show up,” says Clarens. “It’s just like a completely different approach to scheduling, and … what feels to me like a sort of gotcha.”

These tactics are reaching even the most vulnerable cases—those involving asylum-seekers, unaccompanied minors, and victims of violent crime or trafficking.

Attorneys say hearings are being abruptly moved up, sometimes by weeks, leaving little time to prepare. “They’re looking for ways to thwart these processes on technicalities … the consequences shouldn’t be borne by these children,” says Clarens.

Government lawyers are also pushing to dismiss active cases, only for ICE to detain people as they leave the courtroom. Cruz recalls one asylum-seeking group whose hearing went forward—then agents tackled and arrested them outside the courtroom.

“The thing that has been most detrimental, has been the courthouse arrests,” Cruz says. “I can’t ever guarantee to someone that I’m going to go appear with that they won’t be detained. It’s always on the table. So that’s unnerving, … to factor in the fear that you could be detained for simply doing exactly what you’ve been asked to do: … attend all of your immigration court hearings.”

Back to court

Whether it’s in immigration court or the local courthouse, ICE arrests are undermining the entire justice system. Every source C-VILLE spoke with for this story reported increased difficulty getting clients and witnesses to attend hearings, report crimes, and otherwise engage with the legal system.

“It’s an access to justice issue,” says Gregg. “If non-citizens are unable to access the court system, unable to access the local courts, to either defend against criminal charges or vindicate their rights as a witness or a victim, that kind of issue impacts all of Virginia, all the communities, when any one group is unable to seek justice through the court system.”

According to Clarens, “People can’t access justice in a community where ICE is just lurking in our local courthouses. I think all local practitioners spend a lot of time getting calls from people who don’t want to go to court.”