India Sims’ favorite place in Charlottesville is 5th Street Station, the large shopping area anchored by Wegmans supermarket. It’s one of the few places in town where her presence feels expected rather than just tolerated. For Sims, who is in a wheelchair and has been partially paralyzed since she was 10 months old, finding welcoming spaces has been a constant challenge.

5th Street Station does a good job with accessibility, Sims says. There’s plenty of parking, sidewalks have ramps instead of curbs, entrances are accessible all the way around buildings instead of on just one side, store aisles are wide enough to be comfortable for a wheelchair to navigate, and the café-style seating outside Wegmans is easy to use.

“They took it upon themselves to make it accessible all the way around the building,” Sims says. “If you go anywhere else, they don’t do that.”

Sims doesn’t often go to other parts of the city for that reason. She says it’s just too tiring to deal with the frequent obstacles, or even barriers to entry.

“I wanted to take my children to Banana Republic in Barracks Road,” she recalls. “And there’re two steps to get in there, and they don’t help you, so we couldn’t go.”

Downtown can also be deterring for those who use wheelchairs. Many buildings have entryway steps; uneven or widely spaced bricks can be rough to pass over; and the sidewalks are narrow with high curbs. A poorly placed signpost or utility pole can make it too tight for a wheelchair to pass, let alone turn around.

“It’s just like a maze for people that are disabled,” Sims says. “I know that they want that historical feeling, but it’s not going to hurt anything to just put some brown pavement there too to help.”

Sims says that the difficulty in accessing public spaces keeps many with disabilities from going out, rendering the population and its needs invisible.

“I see so many people that are disabled that hide in their community because they don’t want to deal with the people out here,” Sims says. “One, it’s inaccessible, and two, there are so many discriminatory people that make them feel unwelcome.”

Disability advocates maintain that we all have different access needs. Whether you speak a different language, come from another culture, or move through the world in a wheelchair, we are diverse, and accessibility means welcoming those differences.

“When we think about access, we should really be considering a human perspective,” says Jess Walters, a disability advocate and artist based in Charlottesville. “[Access] can mean a lot of different things to a lot of different people.”

Design choices determine who a place is built for. A space created for car traffic, for example, looks different than a space for pedestrian traffic. Signs that are in English or in Spanish make a choice about who is being spoken to. Advocates say that those with disabilities are often left out of the picture when spaces are being designed.

“Not providing access ultimately means you’re not inviting disabled people into the room,” Walters says. “Disabled people make up a quarter of the population. We are the largest minority, and yet we often have the smallest amount of influence.”

Walters has Alport Syndrome, a rare genetic disease that damages the kidneys and can cause late-onset deafness.

“So the one I fight for daily is closed captioning and [American Sign Language] interpreters,” Walters says. They say they encounter difficulty getting accommodation for their access needs. The resistance has to do with how people with disabilities and accommodations for disabilities are conceptualized, they say.

“Because we’re socially a burden,” Walters explains. “Therefore, our access needs are a burden.”

In their artwork and activism, Walters seeks to shift how disabilities are viewed.

“The focus is always on how to fix what’s broken, it seems,” they say. “A mantra within the community is, ‘We’re not broken. Society is broken for not including us.’”

Walters advocates for a more humanistic perspective. That is, thinking of a person with disabilities as whole rather than someone with a piece that’s missing—whether it’s hearing, sight, mobility, or something else.

“When you look at us from a deficit-based perspective, you sort of only see the negative and you don’t really get the larger picture,” Walters says. “That moves away from that sort of humanistic, holistic viewpoint which, I think, does us disservice because it ultimately eradicates variability.”

Walters says the needs of a person with disabilities are historically viewed as “needier,” when they should be viewed as “different.”

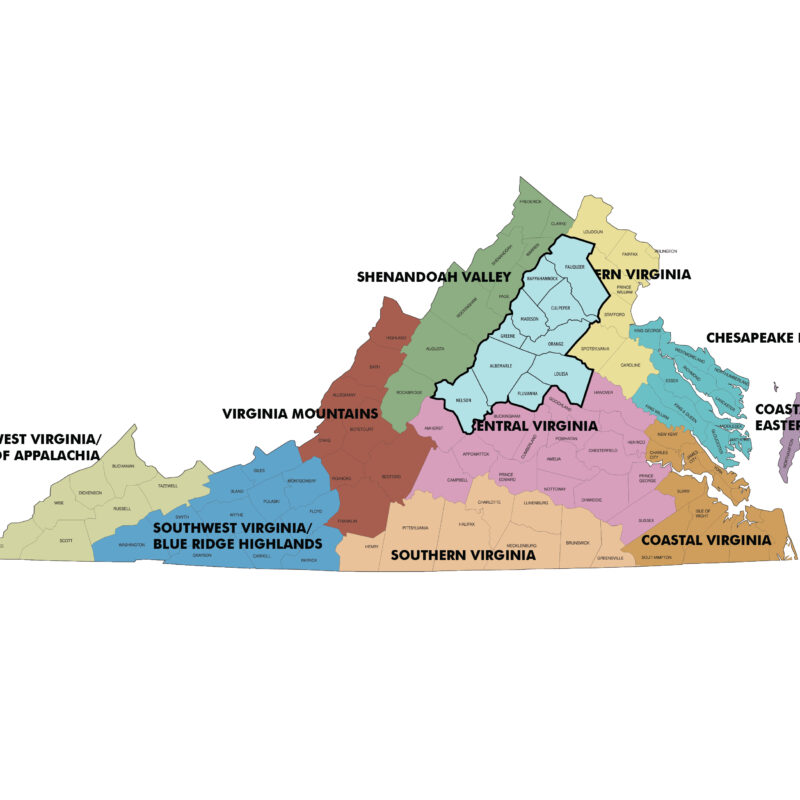

In Albemarle County, 9.3 percent of the population lives with a disability, according to 2021 U.S. census data—almost one in 10 people. Providing equal access requires acknowledging a spectrum of different needs.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 makes up the major legal infrastructure to prevent discrimination against people with disabilities. The ADA addresses equal access to employment, state and local government services, businesses, and nonprofits, as well as telecommunications. The act includes requirements for sidewalks, buildings, sign language interpreters for government programs, and provision of reasonable accommodations for businesses and employers.

However, implementing those standards can be difficult.

Sarah Pool knows ADA requirements as well as anyone, and better than most. Diagnosed with a degenerative eye disease at the age of 16, she was legally blind by age 30, and now, at 63, she sees only spots of light in a fog. Getting around is a challenge for her, and a major hurdle of living with blindness.

“It’s not a lot of fun when you’re walking down the sidewalk and suddenly you’re smacked in the face with a branch,” Pool says.

Pool walks with a cane, but it goes right under trees and shrubs that reach into the sidewalk. The ADA does have a regulation for that: Vegetation may grow no more than four inches into walkways.

Pool has been active in addressing complaints about accessibility to the city’s ADA coordinator for the past 15 years—some for vegetation, and also frequently regarding the regulations for detours around construction zones.

Pool says some of the problems that she’s noticed include the cross-slope of sidewalks, the slope from side to side, which should not exceed 2 percent under ADA regulations. Many sidewalks are also narrower than the required 36 inches and, Pool says, there are over 200 places that are missing required curb ramps where they should be.

Paul Rudacille, who was appointed ADA coordinator for the city last year, agrees that Charlottesville has some shortcomings.

“Charlottesville, like a lot of cities, at least older ones on the East Coast, was built before the Americans with Disabilities Act or the Rehabilitation Act, which is older than the Americans with Disabilities Act,” Rudacille says. “So, a lot of things do need to be upgraded.”

Rudacille says that Charlottesville is currently undergoing an ADA transition plan, a required self-evaluation of physical barriers that limit accessibility throughout the city. He says that city contractors will be looking at every single curb ramp, walking every sidewalk, and evaluating crosswalk signals.

Precision Infrastructure Management, hired by the city to conduct the audit, is in the process of assessing all public facilities in Charlottesville to find out if they meet ADA criteria. For example, contractors are looking to see if curb ramps are where they should be and if they have the proper grade and tactile warning strips for pedestrians who are blind. For pathways, they’re evaluating whether they are wide enough, if they have obstructions such as signposts, and checking for vertical height displacements—tripping hazards where sidewalk panels have come apart and become uneven. The assessment is currently looking at right-of-ways in the city but will also cover facilities, parks, programs, services, and the city’s website. The evaluation is meant to be in-depth, comprehensive, and detailed.

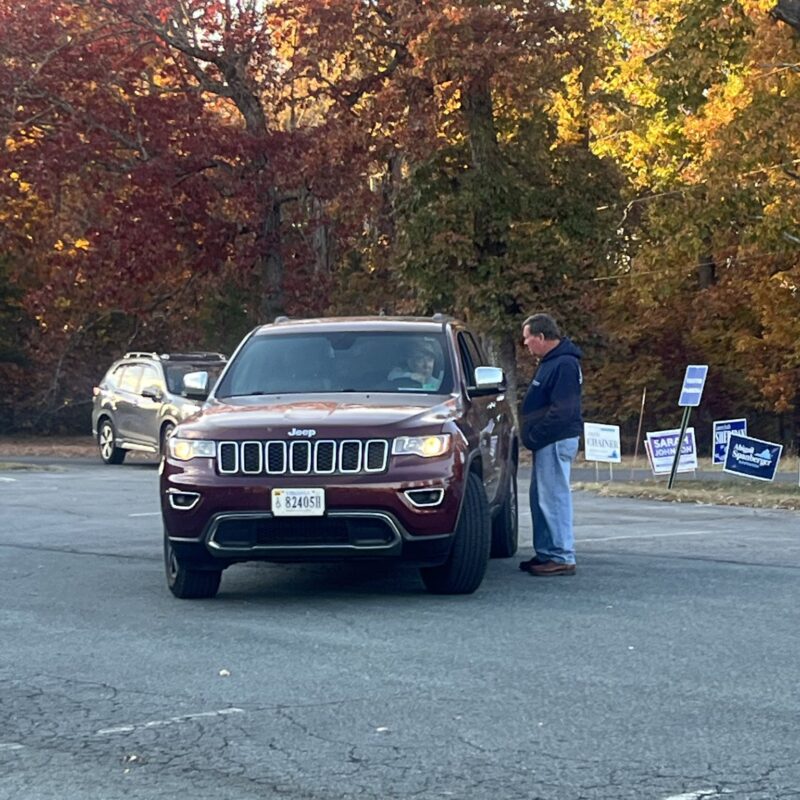

A major component of the transition plan is community outreach—input on public services will help shape priorities for the implementation phase of the plan that addresses where improvements should be made and what those improvements should be. A survey is available on the city’s website for residents to offer feedback, a more open forum for engagement is on the schedule, a town hall-style community meeting was held September 20 at CitySpace, and another is planned for December.

“Primary consideration should always go [to] the person with the disability,” Rudacille says. “Some people want accommodations, and some people don’t want accommodations.”

Rudacille points out that awareness is also key to providing accessible services. Charlottesville has many accessibility services in place already. JAUNT is a reservation-based, accessible transit service that residents can use to travel to areas Charlottesville Area Transit doesn’t reach. The city is required to provide closed captioning or ASL interpreters for public programs upon request. Municipal web pages are also required to work with text-readers so they are accessible for people who are blind.

Pool hopes the transition plan will also include a training program so that city employees know how to connect people with the accommodations that are available. Overall, Pool is very happy to see the transition plan underway.

“This is probably one of the most significant things the city has ever done,” Pool says.

However, the city’s jurisdiction only goes so far. ADA regulations also address requirements for private businesses and non-governmental entities, but enforcing those standards is more difficult.

Sims has run into such problems in the private sector. She says she’s had trouble getting a loan to start her own cosmetology business. The reason, she says, is discrimination. Despite having a license, she believes the lenders didn’t think she could succeed because she’s in a wheelchair.

Employment has also been a challenge. Sims says she has had 30 interviews in the past year.

“On the phone, amazing,” Sims says. But she says the tone changes when employers find out she uses a wheelchair. “They never call me back.”

Kim Forde-Mazrui, a professor of law at the University of Virginia, says that in addition to prohibiting conventional discrimination, the law also gives employers an affirmative obligation to accommodate a disability. That means an employer is required to determine whether a reasonable accommodation could be made to allow a person with a disability to do a job.

“For example, I’m legally blind,” says Forde-Mazrui. His employer, the UVA School of Law, is required to determine if there is a reasonable accommodation he would need for the job. In fact, he does use software that can read his computer screen aloud for papers and textbooks. “They have to work with someone with a disability before they just decide that someone with a disability can’t do the job.”

However, it’s hard to prove that someone wasn’t hired because of their disability.

“That’s very difficult,” Forde-Mazrui says. “Which is why employment discrimination cases are so hard to win, because so often they turn on the subjective motivation of the employer.”

In Albemarle County, just one in four (24.4 percent) people with disabilities are employed and one in 10 (10 percent) live below the poverty line, according to 2021 U.S. census data. In national averages, those with disabilities are less than half as likely to be employed and twice as likely to live below the poverty line.

Sims says affordability is a major concern for her as a person with a disability and should be part of the conversation around access.

“I want accessible housing for people that are disabled. I want us to be able to go get a home without a problem. I want us to be able to get a loan so that we can start a business, any business that we want. I want everyone that doesn’t want a business to be able to work.”

That is the future she says she’ll continue to work for.