With three series of black-and-white photographs depicting various aspects of the human form, “Holly Wright: Vanity” brings themes of corporeality, communication, and mortality into focus. Wright, who taught photography at UVA for 16 years and helped build the university’s museum collection of photo-based works, presents lyrical and contemplative images in her first solo show at The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia.

In the “Vanity” series, Wright offers tightly cropped closeups of her own hands. The photos depict fragmented forms in soft focus. Ridges of fingerprints and folds of flesh allude to the haptic—to touching and being touched. In the “Poetry” series, Wright brings forth a study of the mouth of her Pulitzer Prize-winning husband. Composed in the tradition of photographer Eadweard Muybridge to show sequential motion, more tightly cropped images create a visual rhythm within the picture plane and the installation itself. Where the “Vanity” series is installed in a straight line, creating a syncopated kind of visual rhythm, “Poetry” is installed at varying heights, in mimicry of the rise and fall of human speech. We see the shape of the mouth change, illustrating an expression of words that are absent. In place of the sonic reality of the poetry, the viewer is prompted to fill in the gaps.

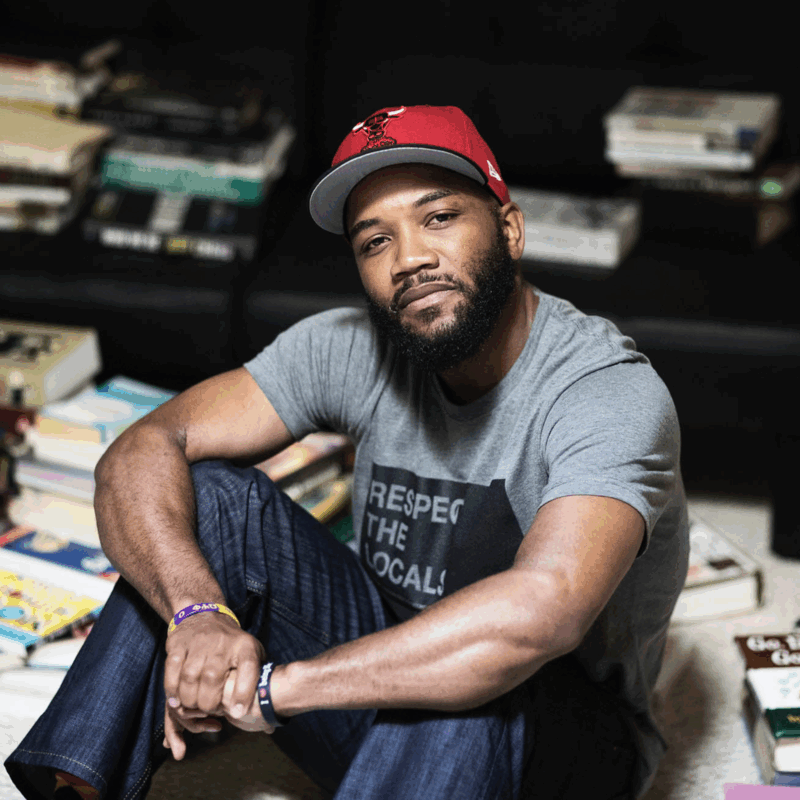

Wright’s “Final Portraits” series represents the most affective and impactful works in the exhibition. Alluding to funerary scenes, the set of eight portraits asks how each sitter would face death as captured in the act of an imagined final photograph. The viewer is immediately implicated in the series through scale. Presented in life-size prints, the subjects stare out at the audience, acknowledging that death will come for us all, and asking how each of us will face it. The images are simultaneously arresting and somewhat comforting. The subjects express palpable aspects of agency, even in the face of the inevitable. Apparel, adornments, and postures all speak to how we see ourselves, and how we want to be remembered when we’re gone.

Of the eight images included in “Final Portraits,” four feature couples—including the artist and her husband—underscoring that some will greet the end alone, and others together. The youngest subject, Wright’s son, shown grasping a repeating rifle with a hunting knife and hatchet affixed to a belt at his waist, conveys a kind of subdued surprise. A young woman in cowboy boots expresses a form of defiance, arms crossed, eyeing the camera lens suspiciously. The backgrounds of the portraits include grass, asphalt, and bedding, conjuring connections to earthen soil, artificial rigidity, and the comforts of home.

The series presents ruminations on mortality, but also of time, appearance, and what it means to inhabit a body, if even for a brief time. Good art can make us think, feel, confront uncomfortable truths, or turn away—Wright’s work asks all of this from the viewer, presenting an exercise in ephemeral awareness as we enter a new year.