A few leafy green hemp plants sit on the second-floor windowsills in the Charlottesville Cannabis Club’s lounge. A puffy, white sectional couch fills the center of the room. The high-ceilinged space is a little brighter than the tapestry-draped basement you might expect at a members-only marijuana club, though there’s plenty of evidence that stoners dwell here: A bright green print of a weed leaf hangs on the wall, with bullet points taking visitors through a brief worldwide history of cannabis.

Matt Long, the tall, stubbled, 30something proprietor of the month-old business, shows me around the lounge. There’s a projector aimed at a blank wall—for “Cheech and Chong, or a football game,” Long says. He points out the snack bar, where bags of chips and cookies are on sale for patrons who might get hungry.

It’s four o’clock on a Thursday. Two men sit at the lounge’s table, swapping observations about each others’ vape pens, and a soft herbal aroma fills the air. A battered copy of The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll sits on one coffee table, a box set of the complete works of Calvin and Hobbes on another.

The Cannabis Club is a new venture, a result of Virginia’s stop-start overhaul of the state’s marijuana laws this summer. The commonwealth’s Democratic majority voted to legalize recreational marijuana sales starting in 2024. In the meantime, in an effort to depress arrests, Virginians are allowed to possess and consume marijuana in private spaces, but aren’t allowed to smoke in public.

“Since you can consume in a private setting, we created a private members’ lounge,” Long says.

For $200 per year, club members can stop by the rooms above Ten Thousand Villages on the Downtown Mall and smoke to their hearts’ content, before heading out, bleary-eyed, toward Charlottesville’s restaurants, bars, and music venues. And anyone can come up to browse the glass-topped counter full of non-psychedelic marijuana-adjacent CBD and Delta 8 products.

It’s a new business model for our stuffy old commonwealth. Long, though, isn’t exactly new to this game. In fact, he’s cannabis royalty.

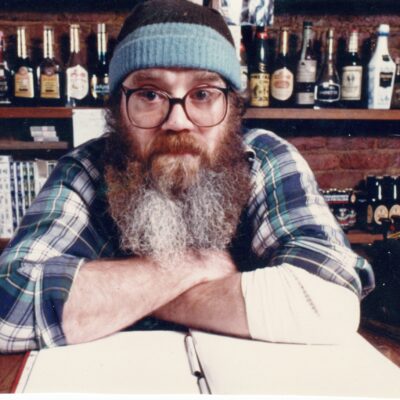

Photo: Eze Amos

All in the family

In the 1970s, Charlottesville native and Western Albemarle High School graduate Allen Long smuggled a million pounds of pot into the country. Allen flew rickety planes into the Colombian brush to pick up product. He nearly found himself on the wrong end of a Cuban-American smuggler’s gun. He made $25 million. He was the subject of a 2002 bestselling book, Smokescreen: A True Adventure, by Robert Sabbag.

Allen Long—Matt’s father—attracted the attention of his hometown, as well. His face graced the cover of the very first issue of The Hook, the Charlottesville alt-weekly that published from 2002 to 2013.

In his heyday, Allen “was spending his millions, doing coke day and night, wearing thousand-dollar suits, leasing a jet year-round and tipping the pilot $10,000 at the end of each flight,” wrote The Hook. He had “balls like a bull elephant’s—with charisma and cunning in the same large measure,” reads the back cover of Smokescreen.

Eventually, Allen Long’s luck ran out. He spent five years in jail, starting in 1992, when Matt was a little kid.

The Hook story portrays the recently-freed Long as a reformed man, participating in local charities and trying to raise his children the right way. Allen told The Hook that he’d send his kids to military school if they got caught smoking pot. He kept that promise—Matt did a stint at Hargrave Military Academy in Chatham before graduating from Western.

The older Long wasn’t reformed, however. He got back in the game, and went back to prison. Allen Long did three more years for smuggling, starting in 2006, and passed away in 2012.

Growing up, Long knew that his dad wasn’t like all the other dads in the carpool line. “The book came out when I was in high school,” Matt remembers. His classmates “made interesting remarks [about] it,” he says wryly.

“A lot of them read it, and did papers on it—they’d turn it in for class,” says Long. “The teachers would stop me in the hall and be like, ‘this is not your dad is it?’ And I’d say, ‘No it’s not my dad.’”

It wasn’t always easy. “There were times where it was shameful,” Long recalls, especially in the conservative central Virginia of 20 years ago. “‘Oh, you know, that kid’s dad is a drug dealer.’ That was a real remark from time to time.”

“And he was a drug dealer,” Long says. “So what could I say about it?”

The younger Long doesn’t remember his father expressing much remorse for the smuggling itself. “He was regretful of how much time he spent away, incarcerated,” Long says. “He fell into that industry, and fell in love with it, and became successful at it. When you become successful at something, it’s kind of hard to pull out of it.”

Matt’s mother, Simone, still lives in the area. How does she feel about her son getting in to the business? “I think she’s proud of what we’re doing, and would like to see it continue,” Long says. “The cannabis industry, it’s always been around. So it’s good that it’s going legal.”

In business

The younger Long says he’s keeping everything clean. The Cannabis Club has a storefront of sorts, and a lawyer, and a UVA intern. “We are working with legal counsel, we’re trying to do things above board and pay taxes,” Long says. “I don’t want to go to jail.”

Matt moved to Los Angeles after college to work in finance, but remembers visiting a hash bar in Hollywood and understanding the legal pot industry’s possibilities. When Virginia legalized growing industrial hemp in 2018, Long returned home and started his own farm. It’s called Smokescreen Farm, after the book about his father, and is the origin of many of the products for sale at the club.

“I am doing some of the cannabis stuff to keep the heritage going,” Long says. And having dad’s connections is helpful. “We have family friends and stuff, farmers in California that we’ve known for a long time. It’s a second-generational business now.”

Long hopes to turn his space above the mall into a full-fledged marijuana dispensary when it becomes legal to do so in 2024.

The state will hand out a limited number of dispensary licenses, but the Charlottesville Cannabis Club will have a good shot at getting one. Virginia plans to issue some dispensary credentials through a social equity licenses program, designed to help people who have been affected by the racist enforcement of drug laws get a foothold in the new cannabis industry. If you’ve graduated from an HBCU, live in an “economically distressed” area, were convicted of a marijuana-related crime, or have a direct family member who was convicted, you can apply for a social equity license. Long, because of his father’s record, will be able to apply through this program.

“People whose lives have been ruined by some sort of cannabis conviction—doesn’t matter what color you are, but specifically minority folks—they should definitely have a right to some sort of ownership in the industry,” Long says.

At this point, the local CBD and cannabis industry is predominantly, if not entirely, white-owned. The committee engagement director for the city’s Chamber of Commerce says she isn’t aware of any Black-owned CBD businesses, and the Office of Economic Development doesn’t know of any either. The Charlottesville Black Business Directory also doesn’t show any businesses operating in that industry.

In the few weeks that he’s been open, Long has attracted 45 members. He hopes to reach 150. He also plans to have live music performances and art exhibitions in the large showroom area, where psychedelic paintings hang opposite the glass case of products.

Earlier this year, Long’s Smokescreen Farm paired with Three Notch’d to create a hemp-based beer. (Three Notch’d marketed the beer as a “big, pungent, super dank IPA.”) You’d be forgiven if you mistook Long for one of the many craft brew masters wandering around the central Virginia countryside. He’s a millennial white dude brimming with enthusiasm for his locally made product; he’s wearing a baseball hat and a T-shirt with his company’s name written in a curly font.

Ultimately, the goal is to be the Devils Backbone of weed, Long says—“a solid operator in our own backyard.”

New leaves

Late afternoon light filters through the smoke of the members lounge. “It’s cool to be able to have a spot to duck in, be with friends,” says one club visitor, in between bong rips. “It’s gonna build a community.”

The conversation soon drifts easily to recollections of exactly where everyone was when UVA’s men’s basketball team won the national title in 2019.

A neon sign in the window reads “open” in looping green letters, advertising the club’s presence to passersby on the street below.

The industry has changed since Allen Long’s time. “You don’t meet people like that anymore,” Long says of his dad. He was like a bank robber in an old western flick, someone who really did the dirty work, says the son.

“Now it’s a real industry. People are seeing the recreational and the medical benefits, and the tax revenue and the employment that can come from this,” Long says. “The green wave is rising.”