Imagine you’re a young person in Africa. Your community is strong and supportive. You have everything that you need—until one day you’re kidnapped, put in chains, and packed tight into a ship with hundreds of other people who look like you, but whom you don’t know or understand.

You see others die on the ship right in front of your eyes, but, by the skin of your teeth, you survive. In this unfamiliar land, you’re forced to do backbreaking work without any pay. And if you resist, you’re killed or beaten within an inch of your life.

But over time, you learn how to survive in this system, and teach your children how to do so. From generation to generation, these survival mechanisms—as well as the trauma you experienced—are passed down, not just by word but in your descendants’ DNA.

At Charlottesville’s last Liberation and Freedom Day event, on March 8, Dr. Jessica Young Brown used this scenario to explain the topic at hand: African American intergenerational trauma.

Research into intergenerational trauma, an emerging field of study in psychology, explores “whether and how mass cultural and historical traumas”—like the Holocaust, the Khmer Rouge killings in Cambodia, or the enslavement of African Americans—affect future generations, according to a 2019 article in the American Psychological Association’s Monitor on Psychology.

On Sunday, dozens showed up at City Space to hear Young Brown, a licensed clinical psychologist (among other things), who said her own interest in the subject was sparked by reading Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome by Joy DeGruy.

According to DeGruy’s work, the trauma African Americans experienced during chattel slavery and under Jim Crow influences their present-day behavior, and contributes to the modern forms of oppression they continue to face, from microaggressions to police brutality.

“Our ancestors instilled a sense of fear in their children about the dangers of stepping out of line or speaking out of turn. It was to combat the very real and present reality that one wrong step could be a painful lashing or worse: a violent death,” Young Brown explained. “Their great-great-great grandchildren learned this so deeply…[that] the sense of danger follows us, overwhelms us, and keeps us on high alert.”

To survive in a world “that was not meant for [them],” African Americans have ultimately learned to “focus on forward movement and act strong,” Young Brown continued. But that has left them without the tools to properly express, manage, and reckon with their emotions—and, in turn, heal from generations of trauma.

However, there are steps African Americans can take to heal, beginning with recognizing the trauma they’ve endured, Young Brown said.

“For centuries, the world has denied what occurred to us, and our responsibility is to say, ‘no, this happened,’ ‘no, this impacted us,’ ‘no, this trauma is in our blood,’” she said. “Once we acknowledge there is a thing to mourn, we can move forward.”

Young Brown went on to explain how African Americans can acknowledge their trauma at different levels. At the family level, they can facilitate healing through their parenting practices. While for generations, African American children have not been allowed “to have feelings,” African American parents today should teach their children how to express and regulate their feelings, or they will not be able to do this when they’re adults.

And as a community, African Americans can work together, instead of against each other, to heal, such as by buying from black-owned businesses and getting involved in black community organizations.

“I don’t actually believe we will ever end racism,” Young Brown admitted at the end of her speech. “But what I do believe is that if we do this work…we can feel what freedom feels like—even if the environment doesn’t want us to have that reality.”

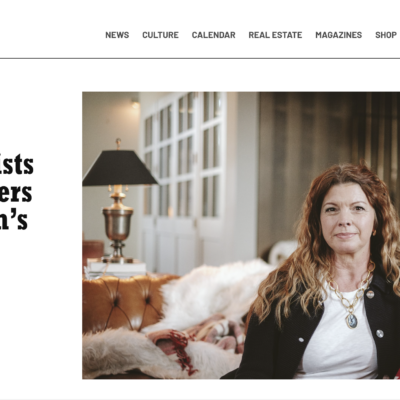

Dr. Jessica Young Brown spoke to a full crowd at CitySpace Sunday afternoon about African American intergenerational trauma for Charlottesville’s final Freedom and Liberation Day event.