“My upbringing was pretty weird,” says David Bowie’s son. I know: You’re thinking, “No way.” But sure enough—or so Duncan Jones, the artist formerly known as Zowie Bowie, told the New York Times a few weeks ago.

Jones was recalling the formative years during which his father introduced him to the likes of George Orwell, J.G. Ballard and Philip K. Dick, and let him hang around the set on movies such as Labyrinth. Now Jones has made his own film, the dauntingly pedigreed but quite self-sufficiently entertaining Moon.

|

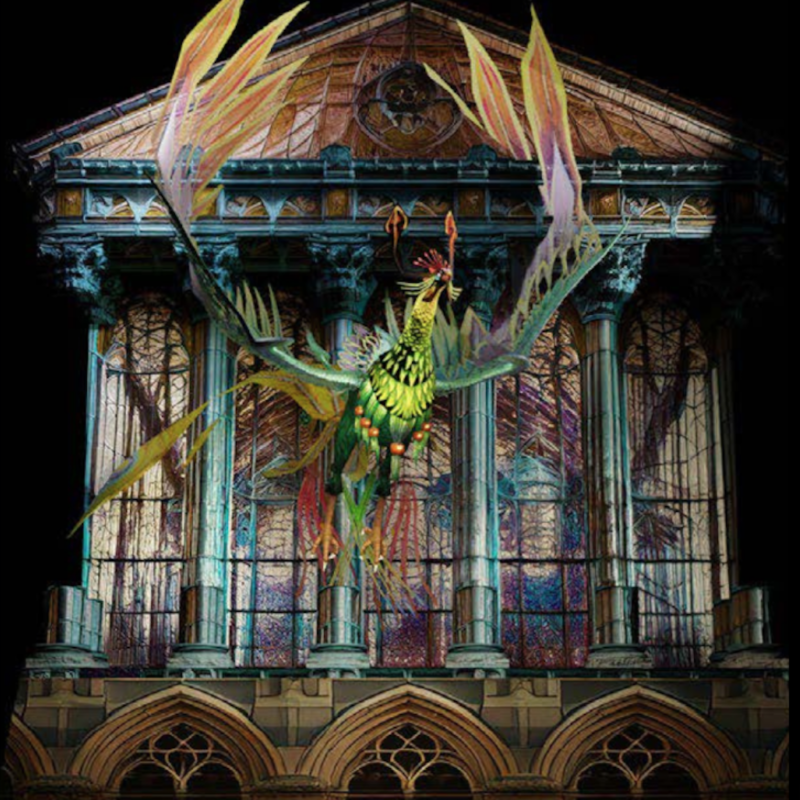

I’m a Rockwell man! David Bowie’s son directs Sam Rockwell in the loony lunar flick Moon. |

Sam Rockwell stars as a near-future moon base laborer who for three years has, by himself, mined the lunar soil’s rich supply of Helium 3, with which his far-flung administrative overseer claims to be solving Earth’s energy crisis. But that claim is dubious.

It’s hard to say more without giving the plot away, and the plot is best discovered by the audience as it is by the protagonist: gradually, and with a piquant combination of good humor and dread. Of course this plot—developed by Jones with screenwriter Nathan Parker—is also pretty ridiculous. But it’s still less ridiculous than you might expect from a movie by a guy who grew up reading Orwell and Ballard and Dick and watching David Bowie work on the set of Labyrinth.

Let’s just say that Moon takes place on the mysterious frontier between space madness and corporate malfeasance. The important thing about that setting is the quiet, airless brutality of the landscape in which our hero toils, and his sense of distance from civilization and from loved ones. The especially important thing is that he’s alone. That way, when a very unlikely visitor arrives and turns out to be very unpleasant company, you’ll be as freaked out as he is.

In recent years, Rockwell has been building a fine body of work by wondering how men live with themselves, and Moon is all about that. There’s potential for much actorly gimmickry in this role, but Rockwell’s tour-de-force performance never descends. It’s the entirety of the movie, yet also somehow simply one of several essential parts.

Such is Moon’s wily charm. It amounts to an assembly of nice touches—like Clint Mansell’s driving score; or the deliberate tactility of the production design; or the obligatory omnipresent talking computer voiced by Kevin Spacey, whose performances always seem like facsimiles of humanness anyway. (That the computer looks like some contraption from your dentist’s office, and also expresses itself through crude variations on the smiley-face emoticon, only heightens the amusing/unsettling effect.)

As a throwback to the unabashedly philosophical, pre-CGI science fiction of decades past, the assembly works: Moon is a small movie of big ideas. Jones may have inherited some of his father’s spaced-out sophistication, but his film’s real achievement is remaining so down to earth.