Chanell Jackson is home early.

The local resident and mother of three had about seven weeks left on her six-month sentence in Albemarle-Charlottesville Regional Jail when she was transferred to house arrest in late March. She’s one of the 61 non-violent offenders who have so far been released with ankle monitors, as the ACRJ braces itself for the worst-case scenario playing out in prisons across the country: a coronavirus outbreak within the jail.

“It feels good to be home and with my family, especially with everything that’s going on,” Jackson says. “In the jail it’s scarier if you get sick. I don’t feel like I would be able to quarantine properly.”

Jackson’s concerns are legitimate: more than 5 percent of inmates in New York’s huge Rikers Island complex have already tested positive for COVID-19, meaning the jail has a higher infection rate than any country in the world. In Virginia, as of April 8, 11 inmates and 12 staff at the Virginia Correctional Center for Women have confirmed cases of the virus. Some Virginia prisons have had serious health care problems even in the best of times—in 2019, a judge determined the Fluvanna Correctional Center for Women had failed to provide sufficient care after four women died while incarcerated there.

Also nearby, local advocacy groups report that 100 immigrants held in a Farmville ICE detention center have gone on hunger strike to protest their continued incarceration despite confirmed cases of the virus in the jail. The facility, run by the for-profit company Immigration Centers of America, experienced a mumps outbreak last year. ICE denies that the current strike is occurring.

“The jails and prisons already don’t have adequate health care for people who are inmates,” says Harold Folley, a community organizer at the Legal Aid Justice Center. Given the virus, “if you lock somebody up, I feel like it’s a death sentence to them.”

Under normal circumstances, ACRJ has six “hospital cells” for more than 400 inmates.

ACRJ Superintendent Martin Kumer understands the concern. “I want to be clear, jails and prisons are not set up for social distancing,” he says. “They’re designed to house as many people as efficiently and effectively as possible.”

Emptying out

Across the country, advocates have demanded that local justice systems reduce the risk for incarcerated populations by letting as many people as possible out of jails. Some such programs are underway—in March, California announced it would release 3,500 people over the next two months.

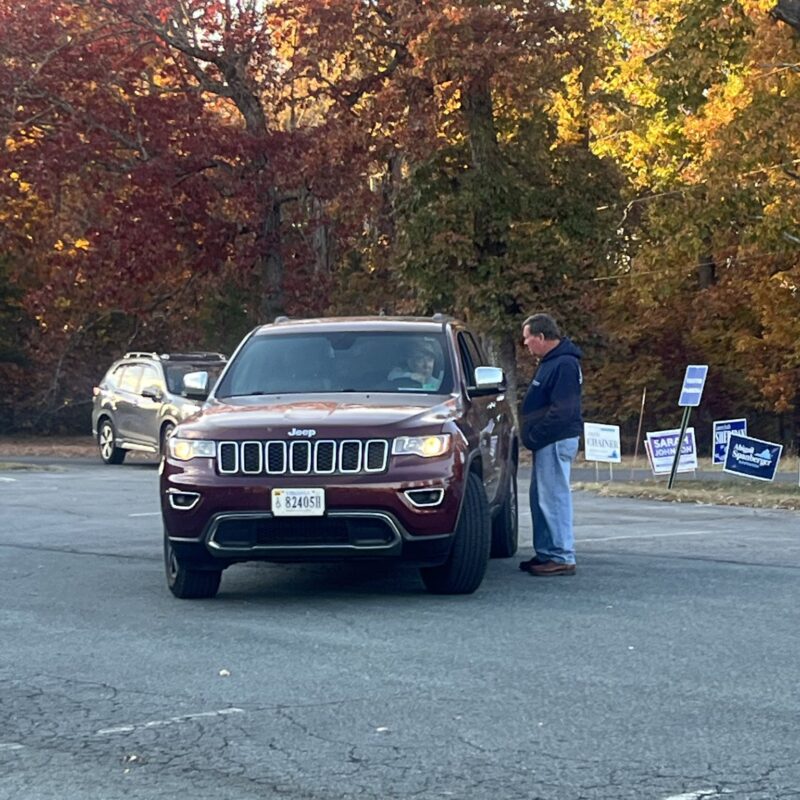

Locally, some prosecutors have enacted progressive emergency measures designed to reduce jail populations. Others haven’t deviated from their usual practices.

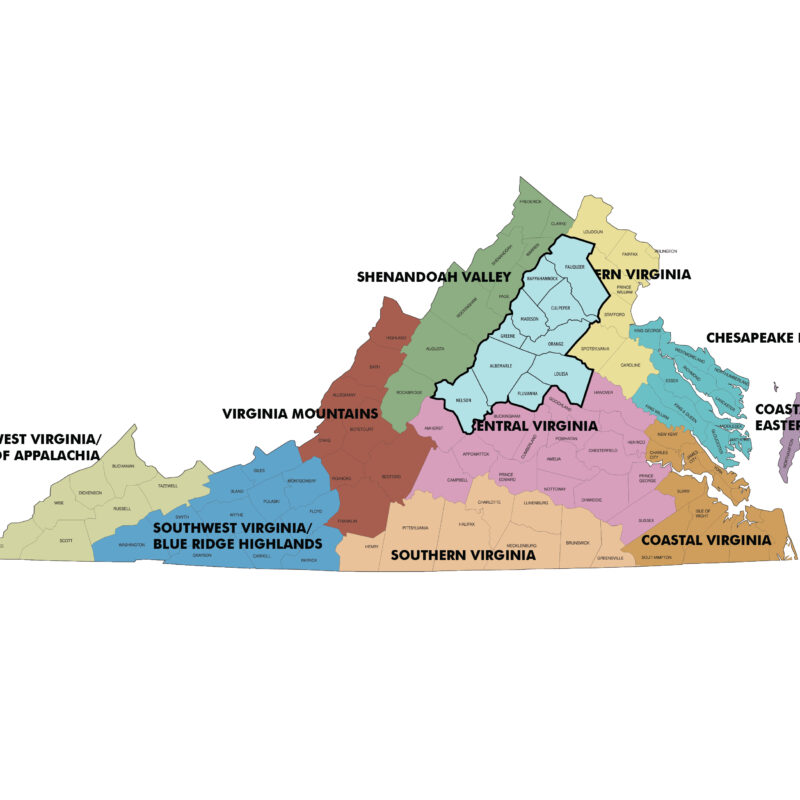

Charlottesville Commonwealth’s Attorney Joe Platania and his Albemarle counterpart Jim Hingeley have worked with the jail to identify nonviolent prisoners with short amounts of time left on their sentences, and transfer those people to house arrest or release them on time served. The commonwealth’s attorneys have also recommended releasing nonviolent prisoners being held pre-trial. That’s resulted in 122 of the jail’s 430 inmates leaving the premises so far.

Nelson County prisoners also go to ACRJ, but Nelson County Commonwealth’s Attorney Daniel Rutherford, a Republican who campaigned on aggressively prosecuting drug crimes, has not participated in the efforts to decrease the jail population, says Hingeley. Rutherford did not respond to a request for comment.

“People don’t understand, the commonwealth’s attorneys have so much damn power,” Folley says. “Joe and Jim have the ability to release people to home monitoring free of charge.” Normally, offenders must pay their own home monitoring costs, up to $13 per day.

“Home electronic incarceration is not release,” says Hingeley, a point Platania also emphasizes. People on HEI are still incarcerated, and can be returned to the jail without any court getting involved if they violate the terms of their house arrest by doing things like traveling without permission or failing a drug screening.

A history of violent convictions will ensure an inmate stays in jail, Kumer says, but there are other considerations, too, like if the inmate is medically vulnerable or where they might go upon release. “We have a large number of individuals who are otherwise nonviolent but they have no place to live,” Kumer says, so they have to stay in jail.

Police Chief Rashall Brackney supports the shift to home monitoring. “I am very confident in the commonwealth’s attorneys, as well as the superintendent, that they are reviewing those cases and taking a very careful look at each of those individuals who would qualify,” she says. That’s a more tempered tone than some other police chiefs in Virginia: “The COVID-19 pandemic is NOT a get-of-out-jail-free card in Chesterfield County,” the county’s police chief wrote in a Facebook post. Last week, two employees at the Bon Air Juvenile Correctional Center in Chesterfield County tested positive for COVID-19.

The jail is emotionally isolating in the best of circumstances, Jackson says, and coronavirus precautions won’t help—all visitation has been halted, except attorneys. The jail is offering two free emails and two free phone calls per week to try to ameliorate the situation. (Normally, an email costs 50 cents—“a stamp will cost you more than that,” Kumer notes—and a phone call costs 12 cents per minute.)

Fewer people behind bars means prisoners can be more spread out and the facility requires fewer staff to operate. Kumer says the plan is to segregate—the jail has emptied out and rearranged one wing to house all inmates who start exhibiting symptoms.

For now, inmates and officials wait with bated breath to hear the virus’ dry cough rattle through the cell blocks. So far, “no one has been symptomatic enough to test,” says Kumer.

Despite these precautions, Kumer isn’t rosy-eyed about the situation. “There’s not a lot we can do if an outbreak does occur,” he says.

Looking ahead

The 308 inmates currently inside the jail is the smallest number in at least 20 years, says Hingeley.

The emergency measures represent baby steps towards a more equitable justice system. The city-commissioned Disproportionate Minority Contact report earlier this year concluded that black people were disproportionately punished at every level of the local justice system. As it turns out, releasing non-violent offenders and people serving short sentences disproportionately helps black people: A little less than half the jail’s total population is black, but two-thirds of the people transferred to HEI due to coronavirus are black.

“There’s a lot of folks who are not paying attention to people who are incarcerated,” says Folley. “When you think of people incarcerated you think, automatically, they are criminals, right. But what people should know is they are human, too.”

“I think they definitely should offer [HEI] more,” Jackson says. “There’s still rules and regulations that you follow, but some people have minor violations and they’re being incarcerated and taken away from their family. At least on home monitoring you can stay home and take care of your family. Because every day is precious.”

Jackson says she loves cooking, and she’s been doing plenty of it since she got home. Her favorite thing to make is lasagna; she just pulled one out of the oven. “I’m very family oriented. I’m very happy to be home with them,” she says. “I have a younger daughter, she’s 1, so I’ve been catching up with her, spending time with her…Everything is mama, mama where’s my mama,” she says, laughing.

Will the change last? That depends who you ask.

“We’re taking some calculated risks with some of these decisions,” Platania says—he doesn’t want to “overreact one way or another.”

He says it’s “absolutely” possible that the local justice system takes a more progressive view of sentencing and bail decisions after coronavirus. “But you know to turn that on its head,” he adds, “if we make a decision to release someone on a nonviolent larceny offense, and they break in to someone’s house and steal something or hurt someone, do we then say well, everything we did was unsafe and foolhardy?”

Hingeley, who ran his 2019 campaign as a candidate for prosecutorial reform and alternatives to incarceration, is more direct. “Absolutely it is my goal to have these practices last,” he says. “From my perspective these are things that we should be doing.”

The emergency measures offer an unusual opportunity to see progressive policies in practice. “We are going to be accumulating information about the effects of liberalized policies with respect to sentences and bail decisions,” Hingeley says. “I am optimistic that that experience—as hard as it comes to us, in this emergency—that experience nevertheless is going to teach us valuable lessons. And we’ll see big changes going forward.”

“I can take the initiative, but other people have to agree,” Hingeley says. Platania also emphasizes that judges are a coequal branch of government to prosecutors, and though there’s been great “judicial buy-in” during this emergency, that won’t necessarily be true in the future.

“I do hope that this will change the system,” Folley says, “but it takes a number of people with courage.”

Updated 4/8 to reflect the number of confirmed cases in the Virginia Correctional Center for Women.