The plan had been to move to the country, renovate an old house, and start gardening. So Marvin Moss bought land in Fluvanna County, restored the 1829 Palmyra manor Glen Burnie, and made plans to plant daffodils.

Moss had worked 36 straight years as an Army officer and a congressional staffer. The time seemed right to rusticate. He was 57.

“I found this place sort of by accident,” says Moss, sitting in a quiet room in the Fluvanna County Public Library, where his name is displayed commemoratively in at least two places. “I was, of course, reading The Washington Post every day, and I was living in Washington, and I was looking at the advertisements for country estates, and I found Glen Burnie, my place, advertised. And so, on March the 17th, 1991, I drove down here with [friends] and saw Glen Burnie all abloom with a whole field full of daffodils. I fell in love with the place. I saw it on Friday and put a contract on it on Sunday. The house had been abandoned for 18 years, but all of the historic structure inside was still in place.”

Moss spent four years restoring Glen Burnie to grandeur. He moved to Palmyra full-time in 1995. And yet…

“I’d lived such an active life that I realized almost immediately when I retired that I had to find a niche here to do something,” says Moss, now 88. “Because I would have been bored out of my skull. When I retired, I was 57—so still of vim and vigor.”

So he helped raise more than $3 million.

Using expertise left over from his life on Capitol Hill, Moss, a former chief of staff to a U.S. senator, won dozens of grants over nearly 30 years through local nonprofits to pay for public works and programs, specifically the development of Pleasant Grove. It also helped Fluvanna absorb a Lake Monticello-led population surge. From 1990 to 2024, the county’s population grew from about 12,500 to more than 28,000.

Moss’ grants have funded a high school, a firehouse, parks, trails, beaches, uncommonly striking picnic shelters, historic renovations and restorations, conservation, museums, nonprofit organizations, one dignified stone bridge, and this geothermal-powered library. It has a neat little brick house off to one side that demonstrates to school kids how solar energy works.

A once and future candidate for Mr. All-Time Fluvanna County, Moss has chaired Fluvanna’s Board of Supervisors and served as president of several local nonprofit organizations, including the now-defunct Heritage Trail Foundation (it had served its purpose, Moss says), the Friends of Rural Preservation (which Moss also founded) and, until recently, the Fluvanna County Historical Society.

Citing age, Moss retired October 19 after 25 years leading the Historical Society. He’ll still be around, though. He’s a member of the board of directors and, now, president emeritus.

“I’m not sure that an awful lot of people realize how special so many of the things we have are,” says Mike Feazel, a longtime Fluvanna resident and journalist who moved to the county from Washington, D.C. He’s written about Moss in the Fluvanna Review. “A lot of them aren’t necessarily things that people who just drive randomly through the county notice. The courthouse is in downtown Palmyra, which nobody ever goes to. The bridge—well, you’re just zooming along at 50 miles an hour, and unless you stop and think and pay attention, you miss it. But it does make Fluvanna something special. … We’re sitting here with all these special things: that courthouse, the jail, the bridge, Pleasant Grove [Park]. I mean, good lord, the fact that that was practically disappearing and he made that into the Farm [Heritage] Museum.

“… Without him, none of this could’ve happened.”

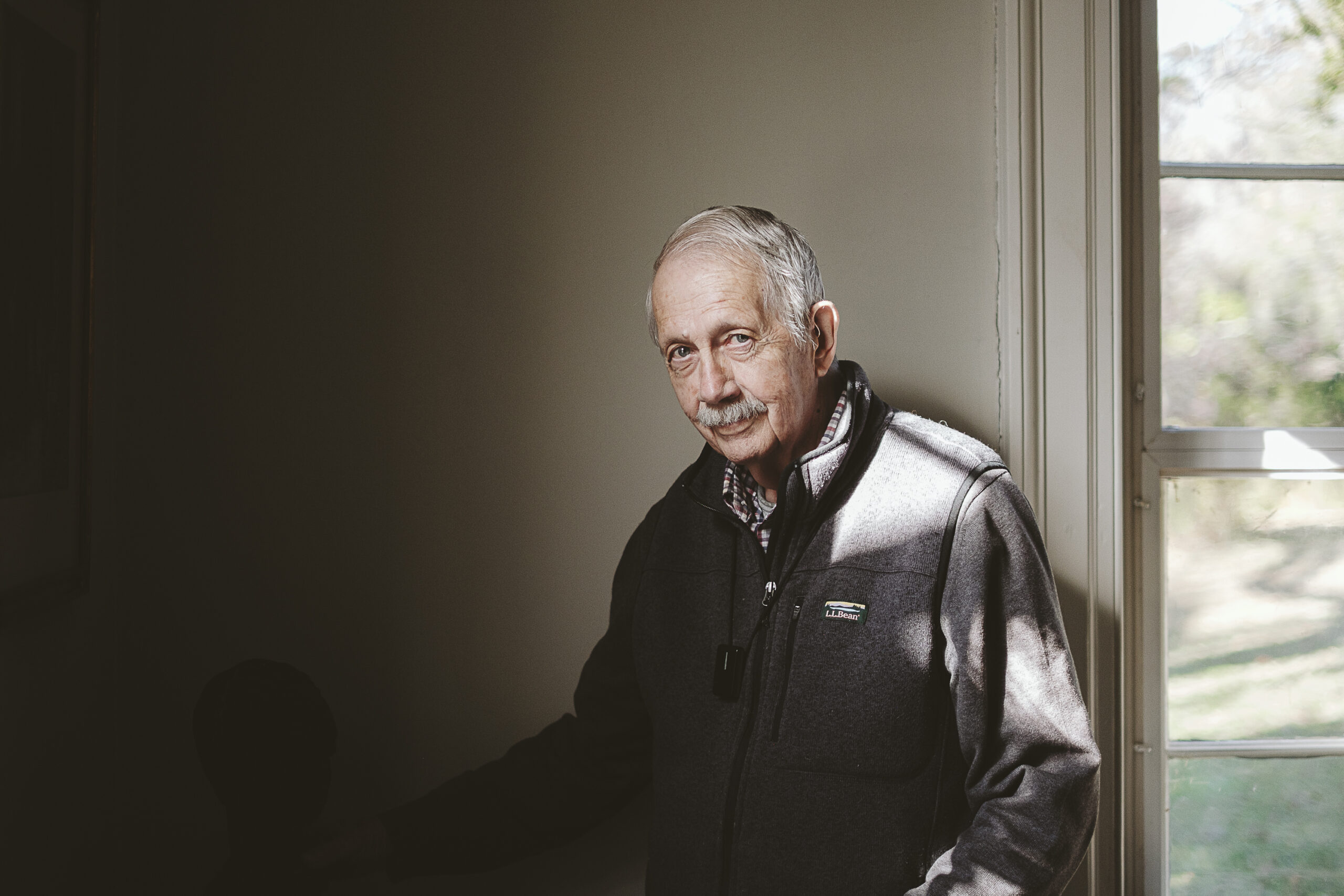

Marvin Franklin Moss, he of the becalming mustache and a compulsive sense of civic obligation, is the sort of being you’d make if you gave a painter’s soul to a textbook. He plays at least 10 “invigorating” minutes of piano every morning, paints (though not as often as he used to), and thinks he would have ended up an architect if not for the Army.

“Loving literature, art, and music opens your mind to the humanist approach to life,” Moss says. “Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote about that. He said it’s that kind of immersion in the arts, literature, etc. that is the kind of broadening experience that brings you the ability to understand other human beings and become a humanist. I consider myself a humanist, which is difficult to define, but I think it’s a person who uses his or her experiences to experience other people. To put it simply.”

It’s a few days from fall, overcast, and the right time for a late lunch if you didn’t already eat. Behind the library, there’s a tree that’s turning orange at the tips like it’s trying to talk to Moses. The library is lively today, by library standards. Decorum and indoor voices still prevail, though someone seems to be reading aloud. You can’t hear them in the quiet room. It’s in a remote part of the library, where Moss is sitting at a table.

He grew up as a “Bud” in the 1940s in Hagerstown, Maryland, where his parents were civically predisposed. His father Benjamin Franklin Moss had stints as president of the Kiwanis and Elks club chapters, and his mother Louise was active with the local art museum and contributed to the local historical society. Then there was Uncle Marvin.

“I suppose my sense of curiosity is innate, although you have to remember my background is unusual,” Moss says. “My uncle graduated from West Point—my mother’s brother [Marvin Jacobs]. He stood in the top of his class at West Point. He was extremely successful in the [Army] Corps of Engineers, and he became essentially the lieutenant governor of the Panama Canal Zone while the United States still owned the Canal Zone, and he came to visit my mother and father, and my Uncle Marvin, for whom I’m named, said to my mother and father, why don’t you send me Bud and my brother Phil to Panama for the summer? And my mother and father, who had never been outside the United States, said, ‘Yes, we will do that.’”

The boys, ages 13 and 14, took a train alone to New York City.

“I will never forget walking through Pennsylvania Station, that enormous Beaux-Arts station built in 1910,” Moss says. “It was the largest, most magnificent train station in the world when it was built, and I can still picture arriving there and being so thrilled at seeing that building and how furious I was when they tore it down later.” The villains did it in 1963 to make way for another Madison Square Garden. “My brother and I then took a cab from Pennsylvania Station to Pier 64 on the Hudson, got on the S.S. Panama with my aunt and her children—Uncle Marvin was already back in Panama—and sailed off to Panama.”

They stayed all summer.

“We saw the aircraft carrier Wasp go through the Miraflores locks,” Moss says. “[Uncle Marvin] took us on a tremendous trip across Gatun Lake and up the Chagres River to check on the rain gauges. Of course, the Panama Canal is completely dependent on the huge amount of rain that the isthmus gets, so we wound up in wooden dugout canoes being pulled by Panamanians going up the Chagres River. I was 13 years old. The world had opened up to me. I was the only person in my high school who had ever done anything like that.”

In 1959, Moss graduated from West Point, too. The Army made him a paratrooper and shipped him to Germany where he “spent endless months on the Czech border, out into the woods of Bavaria, waiting for the Russkies to attack” and learned German. Then, Moss got a master’s degree in international relations from American University while studying in Rhodesia, learned Italian in Ethiopia, and fought with the 101st Air Mobile Division (now the 101st Airborne) in Vietnam.

Moss also spent a few weeks at the Pentagon briefing Robert McNamara. In his free time, though, Moss enjoyed protesting the Vietnam War.

“I think he would’ve fired me [if he knew],” Moss says of America’s secretary of defense in the 1960s. “I felt it was my duty as a citizen to express my thoughts about something, knowing that there was a very good possibility of my eventually having to serve in Vietnam.”

“Probably the most important single skill for us,” Feazel says of Moss, “has been he knows how to maneuver the federal grants. He knows how to maneuver the state grant systems. These systems just don’t work for everybody, but he has always known how to do it, and part of that’s because that’s part of what he did when he was in Congress.”

Moss started on Capitol Hill in 1971. After retiring from the Army as a major, he went to work for U.S. Rep. Goodloe Byron, a Democrat who represented Moss’ home district: Maryland’s 6th. In 1977, Moss moved to the staff of U.S. Sen. Paul Sarbanes, another Maryland Democrat, and within six months became chief of staff.

“Senator Sarbanes’ staff was notable for several things,” Moss says. “One was the emphasis on the restoration of the Chesapeake Bay, which is, for all Maryland citizens, sacrosanct. You know, ‘We love our crabs, we love our bay.’ And he became Mr. Chesapeake Bay. We had a staff, which I helped to hire, that was notable for its outreach to the 24 jurisdictions in Maryland: the 23 counties and the city of Baltimore. And what we did was begin to make those jurisdictions aware of federal grant programs that would benefit them, and we were doing that very aggressively.”

They also formed coalitions of counties and their historical societies, which Moss says were “very strong, but they had never, ever brought their citizens together to discuss what the citizens valued in their own communities. We discovered that the National Park Service had a program of grants to local communities to do exactly that: to plan their own cultural enrichment. And they were called heritage forums. And so we helped them apply for money, assisted them to get the grants.”

Moss brought those forums to Fluvanna, too. They were among the first grants he applied for when he moved.

“I think people respect him, understand [Moss],” says Judy Mickelson, a former Historical Society president and a longtime friend of Moss’. “He’s done so much work and given so much beauty to the county. … Marvin is a curious, kind, thoughtful person who would look at something that might look like a weed to somebody and give you the extraordinary botanical name and the history of it. He might be humming a tune from Schubert. He might have a book in his hand, certainly nonfiction.”

Moss moved to Fluvanna full-time in 1995 after completing Glen Burnie’s resurrection. It now includes a small monastery, where Moss’ friends, the twin Eastern Orthodox monks Father Kyrill and Father Mefodii, have lived and helped plant daffodils since the mid-’90s. The daffodils now cover 10 acres, an increase of “30 or 40 times” Moss says.

The tall brick house is back in the trees from Route 15. The old road eases through downtown, where a Moss grant went to renovate the old jail, among other historic structures, and across the John H. Cocke Memorial Bridge. Named for a local magnate and UVA co-founder, the bridge was another Moss project. Then-Gov. Tim Kaine dedicated the bridge in 2007. Walkable and garnished with stone, it crosses the James River and won plaudits from VDOT.

About five miles away, the Fluvanna County Public Library and the sheriff’s office are neighbors at the end of a wraparound and a lane of crepe myrtles. It’s across the road from Grace and Glory Lutheran Church and it’s all in the thousand acres of a long-gone estate called Pleasant Grove.

“In 1994, Fluvanna County bought this thousand acres, it was like a canvas to me, and I was going to paint on it,” Moss says, “and that’s what I did.”