Charlottesville’s old woolen mill, peering over the Rivanna River on the town’s eastern edge, had been gathering dust for years. Now, the rubble has been cleared, and it’s time to drink beer.

In 2018, app development company WillowTree began a $25 million overhaul of the building. WillowTree’s employees will move into their 85,000-square-foot offices next year. The Wool Factory, an adjacent 12,000-square-foot hybrid space that includes a brewery, restaurant, and coffee shop, has just opened.

The symbiosis between the two outfits is obvious—The Wool Factory is a selling point for WillowTree, as the tech company tries to tempt employees into town, says Claire Macfarlan, The Wool Factory’s director of operations and sales, while The Wool Factory benefits from a “built-in [customer] base on top of the neighborhood.”

The mill itself was originally built in the 1790s, and has “a mixed history,” says Bill Emory, a longtime Woolen Mills neighborhood resident who’s conducted extensive research into the area’s past.

During the Civil War, the mill produced uniforms for Confederate soldiers. Union troops burned down the building, and its associated railroad bridge, when they occupied Charlottesville in 1865, according to the Encyclopedia Virginia.

In the 20th century, the mill grew into Albemarle County’s most productive industry, and the surrounding area became a steady, white working-class neighborhood.

“They had a large, over 50 percent female workforce,” says Emory. “The people who worked at the mill were able to afford housing in the neighborhood. Of course, it was sharply segregated. There was one African American employee in 1920.”

The mill closed in the 1960s, and has since served a variety of purposes. Most recently, it was a storage facility.

“There wasn’t a lot of community interaction with the mill site,” says Emory. “It might have been under-used, but it was never a piece of crap. The previous owners were storing stuff in it so they always took care of the roof.”

Selvedge Brewery, one of The Wool Factory’s three dining options, leans into the setting. It’s full-on urban-industrial brewery chic: The walls are rough brick, the stools are spare metal, and an ancient Remington typewriter sits on a side table. Yellow exposed light bulbs glow from strings above the courtyard.

The Wool Factory comes by some of this character honestly. The green metal lamps that hang from the ceiling are refurbished but original. The gray and white paint—sparse enough to reveal the bricks beneath it—dates back to the building’s industrial days. An original wooden wall separates the kitchen from the dining room in Broadcloth, the Wool Factory’s sit-down restaurant.

“We try to keep it a little bit raw,” says Brandon Wooten, the project’s creative director and a co-founder of Grit Coffee, another tenant. “Normally you have to create the character. We didn’t have to create the character.”

“From the point of view of the historic repurposing and renovation, I’m in awe of the place,” Emory says.

The county’s Architectural Review Board oversees the renovation of historic properties, and the board’s influence can be felt on the property in a few places. An elevated metal chute cuts through the air across the courtyard. “This chute up here that doesn’t do anything had to stay,” says Wooten.

The renovators replaced all the windows in the mill, but had to install window frames that matched the originals. And the lettering on the side of the building—“Charlottesville Woolen Mill,” in squarish white sans-serif—was freshened up but couldn’t be moved, even though the words are spaced oddly, says Lizzy Reid, a public relations manager working with The Wool Factory.

The Wool Factory team says it wants to communicate the history of the building to visitors, but doesn’t have concrete plans in place.

“We’re trying to figure out where that stuff will actually go,” Wooten says. They might put historical information on the menus at Broadcloth, he says, and they “have talked about having something you can scan.”

Macfarlan says they don’t want to install a permanent plaque with historical information, because they wouldn’t be able to remove it during events.

“The names of the beers are very intentional,” says Reid, when asked about the mill’s history. In homage to the space’s original purpose, Selvedge Brewery’s beers are named after fabrics. Patrons can suck down a pint of Seersucker, Herringbone, or even Flannel No. 1.

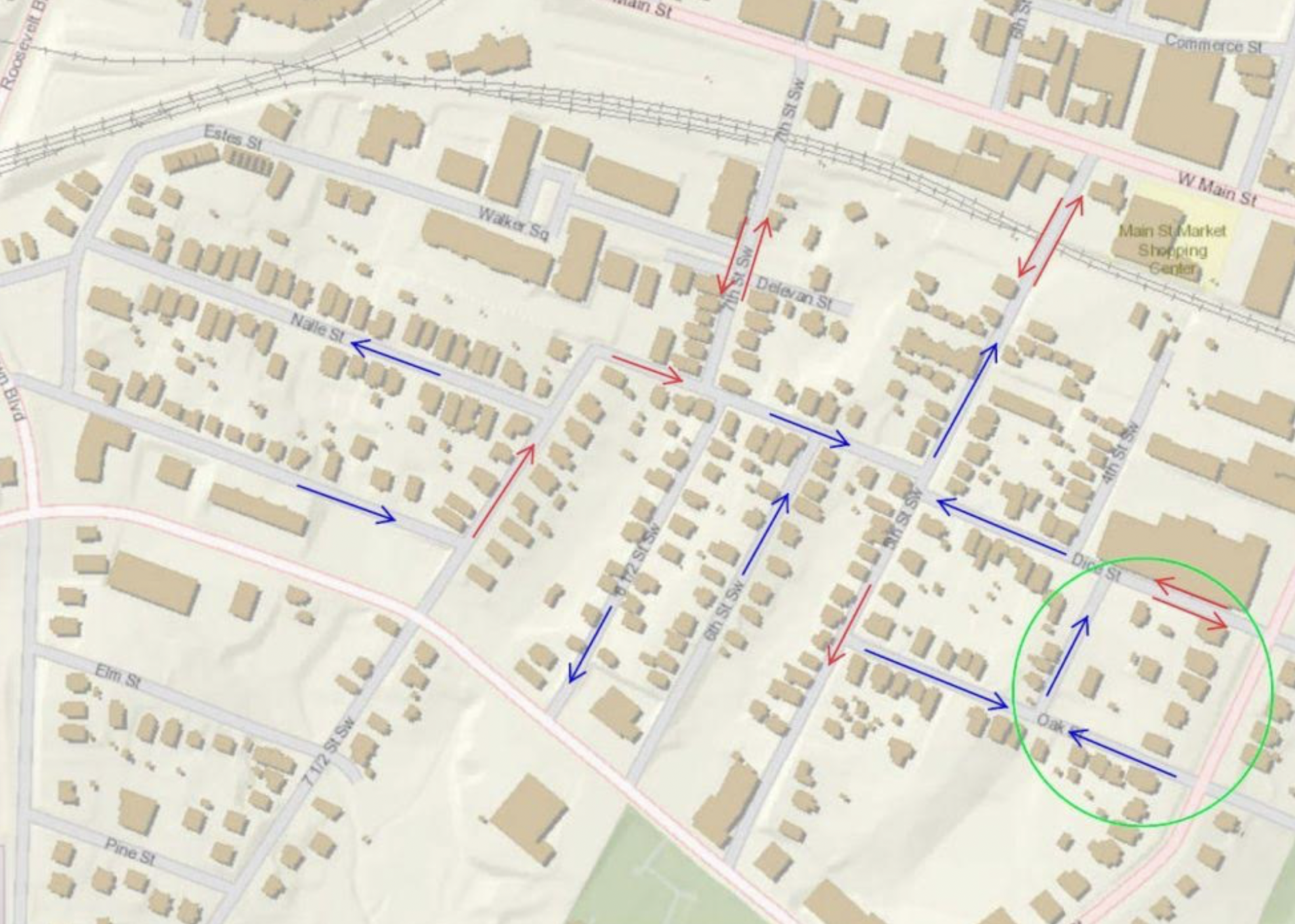

Now, Emory says, the onus is on the city and county to make the building accessible. Broadway Street, which leads through the Woolen Mills neighborhood to the mill, is a “super-wide street with no pedestrian facilities, no bike facilities,” says Emory. “Totally uninviting place to get to if you’re doing anything other than driving a car.”

WillowTree has said it will offer kayaks to those employees ambitious enough to commute to work via the Rivanna. That’s a creative solution, but it won’t be enough to insulate the neighborhood from hundreds of new commuters. (And brewery-goers beware: Kayaking under the influence is illegal in Virginia.)

“It’s potentially a keystone for recreation and a lot of good things happening,” says Emory. “If the county and the city figure out how they’re going to get people to and fro without destroying all the city neighborhoods around the mill.”

This story was corrected 7/9 to reflect that the Albemarle County Architectural Review Board, not the Charlottesville Board of Architectural Review, oversaw the renovation of the woolen mill property.