Up in the Air has a marvelous premise. It says: Imagine getting fired—and not directly by your boss, but by George Clooney on behalf of your boss.

O.K., not Clooney exactly, but close. It’s him playing the part of Ryan Bingham, roving downsizer, despoiler of livelihoods. “Career transition counselor” is how he’d put it, elaborating that maybe this isn’t an ending for you at all, but a beginning, a real opportunity.

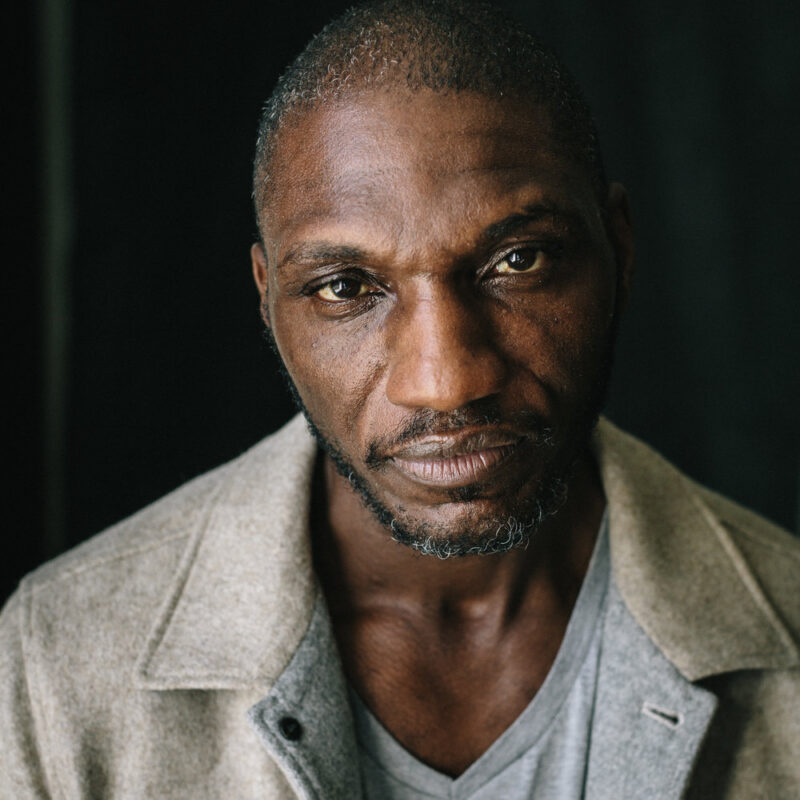

|

Optimists do it looking up: George Clooney tries to keep on the sunny side as a corporate downsizer in Up in the Air. |

Certainly it is for writer-director Jason Reitman, whose ambitious, unnervingly timely adaptation of Walter Kirn’s novel has found exactly the right actor to embody its peregrine protagonist. And in order to transplant him into a film and into today’s economy, Reitman, who shares screenwriting credit with Sheldon Turner, has concocted a rich array of supporting characters and cast them perfectly, too.

It isn’t long before Bingham discovers he’s on the verge of being downsized himself, and accordingly tormented by a grimly driven B-school hatchling (Anna Kendrick) with the bright idea to do their company’s dirty work via cost-cutting video link. “There is a dignity to what I do,” he insists in protest, but we know the protocol of face-to-face firings matters to him mostly as the apparatus of his rootless, frequent-flier lifestyle.

Also, he’s found a like-minded lover (Vera Farmiga), through a rally of mutual come-ons—comparing premium memberships and first-class privileges—in an airport lounge.

“I am the woman you don’t have to worry about,” she says. “Sounds like a trap,” he replies. “Think of me as yourself,” she says, “but with a vagina.” There’s a warning here.

Bingham also has two sisters (Melanie Lynskey and Amy Morton), from whom, not surprisingly, he’s become estranged. The fact of their lives seeming unfairly peripheral to the main story is partly what it’s about.

Clooney’s stylish aloofness has set the movie’s fundamental tone, but it’s the chemistry with these women that supplies its harmonic foundation. Just what does it mean to be this man’s equal, Reitman might be asking, and what is it worth? Up in the Air might have seemed like just another road movie—as viewed from seven miles or so above the road—in which a closed heart gets pried open and risks getting broken. It might have seemed like a classically inclined screwball battle-of-the-sexes comedy. But as the story deepens and the sinews of character emerge, it appears also to contain trappings of great American tragedy. Reitman wants to examine recession-era alienation with clear eyes, but also to salve our most soul-curdling scarcities of opportunity—some of which, his film suggests, are self-imposed.

So imagine yourself among the freshly axed, taking in Bingham’s canned, Clooneyish spiel about anybody who ever built an empire once standing where you are now. As a citizen of late-2009 America, does that make you feel better or worse?