“I remember you from my seminar at UVA. You grilled me pretty hard, as I recall, on the bureau’s civil rights record in the Hoover years. I gave you an A.”

)/JE-FP-173052.jpg)

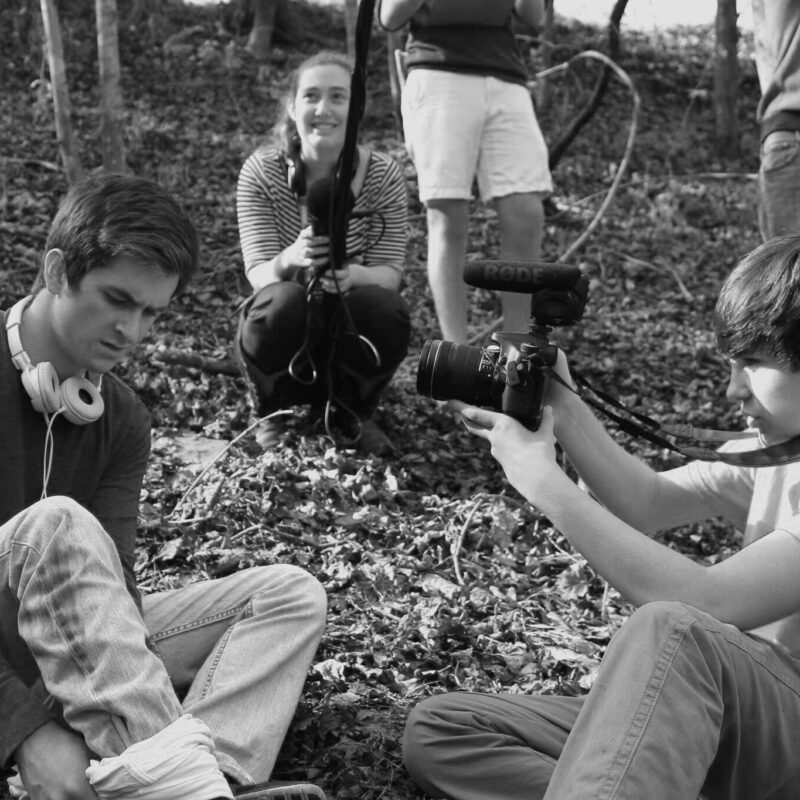

Leonardo DiCaprio plays the revered and reviled J. Edgar Hoover in Clint Eastwood’s latest biopic on the man who ran the FBI for over 40 years.

|

“A-minus, sir.”

Is it possible that one quick volley of expository dialogue, between Scott Glenn and Jodie Foster in The Silence of the Lambs tells us more about how authority works at the FBI than the entirety of J. Edgar?

That might be overstating the case. But after enduring this ploddingly reticent new biography of America’s most famous law enforcement agent, one yearns for a little overstatement. J. Edgar is an inert epic, a mutually neutralizing collaboration between screenwriter Dustin Lance Black, who won an Oscar for Milk, and director Clint Eastwood, who keeps insisting he’s not Dirty Harry anymore. Regarding “the bureau’s civil rights record in the Hoover years,” there will be no grilling here. Just a committed, makeup-caked performance by Leonardo DiCaprio, Oscar-worthy in the most inevitable and perfunctory way.

“We needed more power to protect,” he recalls in voiceover, while dictating to one of his several subordinate biographers. It’s a good, juicily interpretable line, one of too few on offer here, and it gets summarily thrown away. He’s referring to an early appeal that Congress empower his young bureau to carry weapons and make arrests, in the name of public safety. More to the point is the act of dictation, which goes on throughout the movie and is carefully revealed as an unreliable narration of his own political story.

DiCaprio’s Hoover has Naomi Watts as his mannerly secretary Helen Gandy, Judi Dench as his domineering, homophobic matriarch, and Armie Hammer as Clyde Tolson, the right-hand man with whom he dined daily and was secretly in love. On this last front, the movie takes such pains to display compassion and tact that little room is left for any genuine feeling. We’re left with a two-hour lament of how unfortunate it is that Hoover couldn’t come out of the closet.

It seems like Black had in mind something along the lines of Brokeback Mountain with a dash—that whimpering “yes, mother” refrain—of Psycho. An indelicate approach, but a promising one, if it could find the nerve to address the nature of American political power directly. But politics are perpetually and ruinously closeted here too.

Hoover’s legacy includes serious advancements in the application of forensic science to detective work, and sublime advancements in secret surveillance, blackmail, and other means of squashing political dissent. His grudges against left-wingers exceeded even Richard Nixon’s in scope and vehemence. Eastwood acknowledges this but boringly prefers not to comment on it. Enlisting his regular cinematographer Tom Stern to keep things literally shadowy, he succeeds in failing to illuminate.

What we really want to know, and won’t learn from J. Edgar, is what it means to be the top man in charge of earnest young cadets like Jodie Foster’s Clarice Starling, who go work for the FBI because they still wake up in the dark and hear the screaming of the lambs.