Desperate neither to declare the wonderments of digital 3D nor to debunk them, Martin Scorsese’s Hugo does have some preaching to do, on the director’s pet subject of film preservation. Magnanimously, Scorsese won’t say outright that today’s algorithm-rendered pseudo-epics have nothing on the blood, sweat and practical effects of the very old school. It’s all of a piece, he suggests, and ain’t it grand?

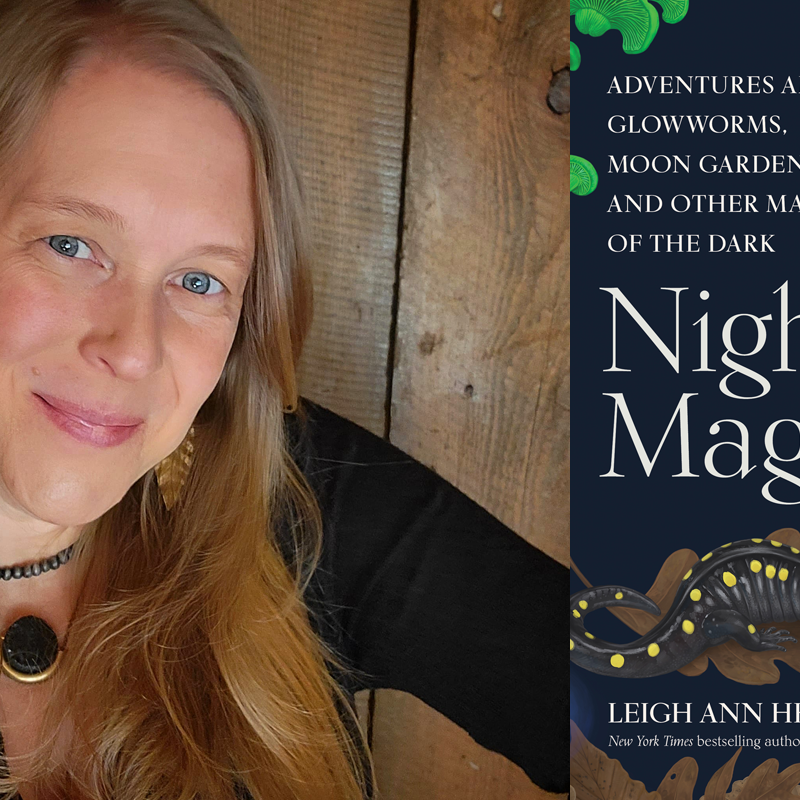

/HugoWeb.jpg) Asa Butterfield stars as the titular street urchin in Hugo, a family-friendly paean to film preservation that is director Martin Scorsese’s first foray into 3D filmmaking. Press photo.

|

Some of it, sure. With its saucer-eyed faces, its jumpy camera zips, and its Paris “of old,” Hugo presents itself at first like some overwrought steampunk confection a la Amélie. Or, more currently, like a segue between the new Sherlock Holmes movie and Spielberg’s Tintin. Its urgency will be in the eye of the beholder.

Hugo (Asa Butterfield) is a watchful orphan living by his wits in the Paris train station whose clocks he maintains. When not dodging an odd, increasingly Peter Sellersish, orphan-hunting cop (Sacha Baron Cohen), he’s swiping occasional croissants and the spare parts necessary to fix a wind-up mechanical man inherited from his dear departed watchmaker father (Jude Law).

The automaton looks like something out of Lang’s Metropolis, and in its deadpan way has one of the movie’s most expressive faces. It’s also Hugo’s connection to the embittered proprietor of the train station toy shop (Ben Kingsley), who won’t allow his adopted daughter (Chloë Grace Moretz) to see movies because he used to make them, and can’t bear to revisit his past. Turns out he’s the early cinema pioneer Georges Méliès, whose 1902 movie A Trip to the Moon was among the first to see the medium’s potential as cutting-edge magic act. But the world seems not to want this “Papa Georges” anymore, and so the boy must also try his hand at fixing the old man’s broken spirit.

Thus, in spite of Butterfield’s quite clever performance, he also becomes a cog in Scorsese’s film-history-appreciation machine. “Time hasn’t been kind to old movies,” someone says, and suddenly it feels like we’ve been watching this on public TV, with our station hosts politely breaking in to ask at length for donations. Good thing, then, that flashbacks to an inspired young Méliès at work have all the vigor and momentum of Scorsese’s best stuff. So much, actually, that it almost backfires: Screw Hugo, we might think, let’s follow this guy.

No can do: Hugo derives from writer-illustrator Brian Selznick’s Caldecott Medal-winning children’s book, The Invention of Hugo Cabret. Screenwriter John Logan shares Scorsese’s evident enthusiasm for the material, and it’s as good a try for holiday-glazed, calculatedly timeless family entertainment as this movie-mad filmmaker could hope for.

Not being above gimmickry for its own sake is part of Hugo’s charm, and its point. As a blessing, it’s mixed. The movie is a kitschy, self-enclosed curio, like some great big cinematic snow globe complete with atmosphere so moist and particle-flecked that even the thought of inhaling it feels a little suffocating. It may well inspire future generations—of art directors and production designers, at least—but in the meantime, remains gleefully preoccupied with commemorating past glories.